You are here

Cyber conflict uncoded

Introduction

When the Supreme Leader of Iran promised revenge in response to the killing of General Suleimani in January 2020, the possibility of offensive cyber operations against US targets was suggested. Eventually, Iran resorted to a more conventional response, launching missiles against US military bases in Iraq. However, this episode points to a shift in our understanding of what conflict means. In January 2019, the French Minister of Armed Forces, Florence Parly, stated that “cyber warfare has begun and France must be ready to fight it” as she announced the new French Military Cyber Strategy.1 In a similar vein, the UK Chief of the Defence Staff, General Sir Nick Carter, announced in September 2019 that Britain is “at war every day” due to constant cyber-attacks from Russia and elsewhere and warned that with the evolving character of warfare, the distinction between peace and war no longer exists in the modern world.2

The proliferation of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), both the expansion of usage and the increased availability of harmful means, has brought about new ways of power projection. Political and economic contestation between states now involves targeted cyber-attacks against other countries’ utilities, financial networks, election infrastructure and governance systems. Cyber-attacks – a deliberate use of malicious software for exploiting or altering computer code, data or logic to cause harm – offer new methods to target internet infrastructure, telecommunications networks, information systems, as well as computers and computer systems. Such activities might have the objective of destroying or affecting the proper functioning of these systems with adverse effects for their users – whether states, companies, public service providers or individuals.3 As a result, power projection does not have to involve tanks or missiles; nor does it have to result in direct death and destruction comparable to armed conflict. Confrontation is, however, a constant in states’ ambitions, attitudes and capabilities, blurring the line between war and peace.

This Conflict Series Brief examines the current practices and future possibilities of preventive action in relation to conflict in cyberspace. When categorising state uses of ICTs as a form of conflict, attention should be paid to three considerations. First, hostile uses of ICTs rarely occur outside of a pre-existing or broader politico-military dispute. Second, a malicious state use of ICTs can lead to an escalation in pre-existing adversarial relations. Third, the use of cyber capabilities in a conflict situation often includes the targeting of civilian infrastructure and therefore has wide-ranging implications for the proper functioning of societies. Against this background, this Brief argues that the use of malicious cyber tools for power projection can and must be prevented.

Old conflicts, new battles

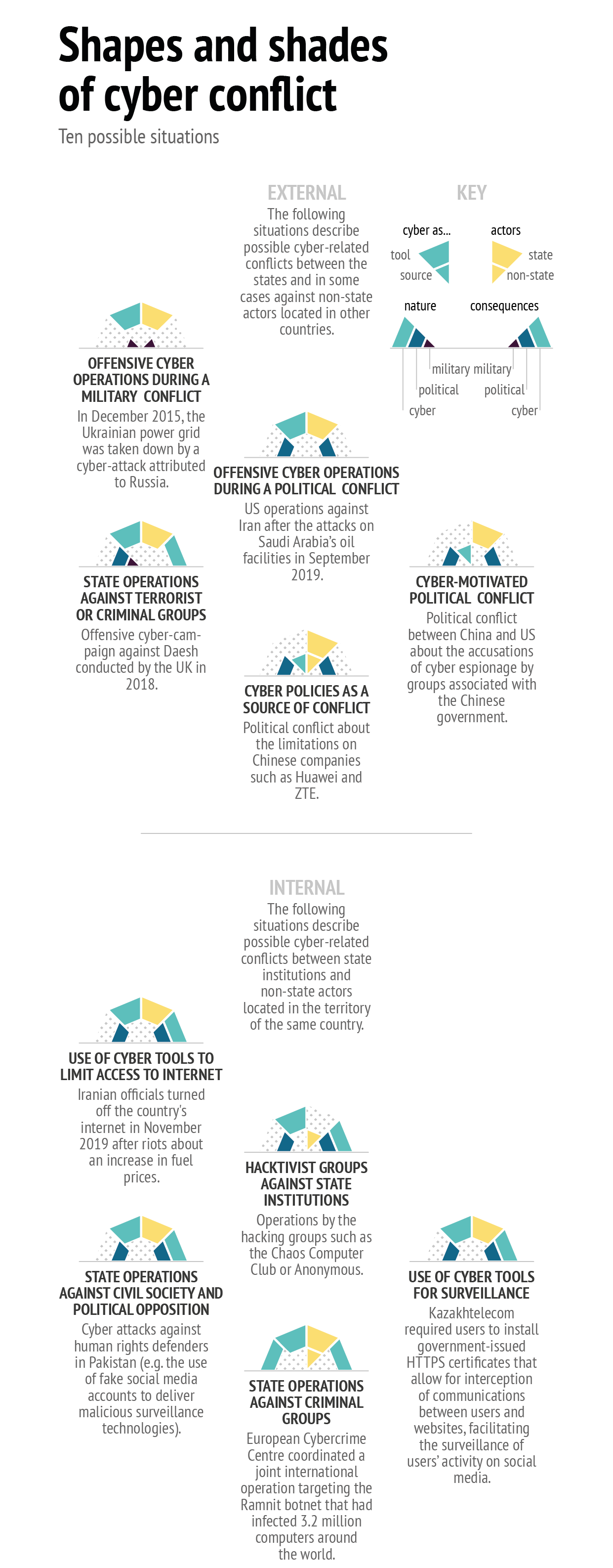

The tacit nature of conflict in cyberspace makes it hard to distinguish where exactly a conflict begins and ends. In its simplest terms, conflict refers to adversarial posturing and propositional incompatibility between two or more parties.4 In this Brief, conflict between states is understood as the absence of ‘friendly’ relations and deliberate adversarial behaviour.5 While the view on what constitutes a conflict has evolved over time, it is universally accepted that international conflict in cyberspace can stem from various ‘real-world’ causes and factors.6

The use of cyber means in the midst of an ongoing conventional conflict is not the only way a cyber conflict can play out. The focus on attacks above the threshold of the ‘use of force’ and an ‘armed attack’ has progressively allowed for a more tacit challenge to emerge: malicious cyber activities that damage state infrastructure, the economy or institutions over an extended period of time.7 While initially cyber-specific in nature, these situations can lead to the escalation of a political conflict. For instance, lengthy cyber-espionage operations aimed at stealing the trade secrets of leading technological companies or key governmental agencies might result in the destabilising of bilateral relations (as seen in the ‘trade war’ between the US and China).

Cyber-attacks can also target the key elements of internet infrastructure which now forms an indispensable element of modern societies: telecommunications networks (radio, telephone lines, undersea cables, satellites), information systems, as well as the processes and protocols underlying the use of the above can all be subjected to attacks. Such activities might destroy or severely affect the proper functioning of these systems (the use of ransomware against hospitals is one example). These hostile activities may involve cyber-specific units, the equivalent to combat arms in traditional conflicts, but states also do not shy away from making use of proxy groups as part of their cyber campaigns.

In recent years, certain categories of cyber activities have been observed as particularly destabilising and hence require concrete de-escalatory responses. Although a tacit tolerance of low-impact cyber activities, disruptive and large-scale cyber operations are likely to invite a cross-domain response, justified, for example, as an act self-defence. The high risk of miscalculation and the escalatory potential of seemingly ‘harmless’ cyber operations are the reasons why the prevention of conflict in cyberspace plays such a critical role. The more we learn to understand conflict as a manifestation of the failed management of mutual disagreements, the better the chances are for crafting effective and timely measures of conflict prevention. Consequently, measures of conflict prevention must be detected, and employed, in various areas of responsibility, in different stages of contestation, and at multiple levels of engagement.

Theory of stability

The complex nature of cyber conflicts and their links to existing political and military disputes make it difficult to design effective, targeted conflict prevention instruments. It could even be asked whether cyber-specific prevention mechanisms are needed at all or should we simply make better use of existing and proven ones? Over the past five years in particular, discussions about conflict prevention in cyberspace have seen a proliferation of different conceptual constructs and approaches without clear definitions. Following an initial focus on the ‘peaceful use of cyberspace’ in the early 2000s, the debate came to be dominated by the loosely defined concepts of ‘stability’ and ‘responsible behaviour in cyberspace’ and more recently, the ‘responsible use of cyber capabilities’.8

The UN Group of Governmental Experts (UNGGE) noted in its 2015 report the importance of the peaceful settlement of disputes. However, most of the measures proposed at the UN level9 focus primarily on promoting state restraint in resorting to the use of cyber tools for malicious operations, encouraging cooperation between states and reducing the risk of misunderstanding and miscalculation in cyberspace. In addition, most of the recommendations fall under institution- and process-building: prevention of harmful ICT practices, exchange of information and assistance, respect for human rights, creating points of contact, and consultations. The establishment of national bodies, the nomination of national contact points, the exchange of best practices and national views and the reporting of vulnerabilities are all aimed at fortifying the coordination and cooperation links between participating states. Moreover, all of these measures are rooted in the assumption that closer ties between states and their institutions will ultimately reduce the risk of conflict in cyberspace.

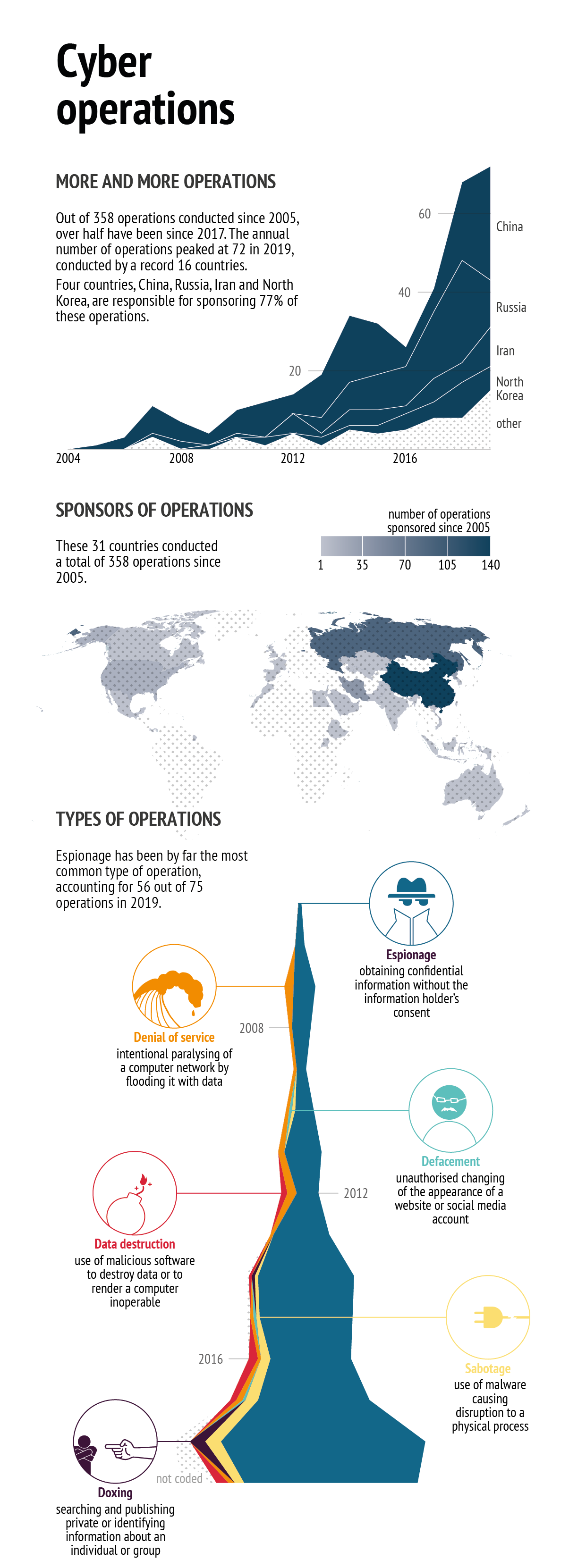

Data: Council on Foreign Relations, 2020

However, existing approaches provide limited predictability and no lasting remedy. As a matter of fact, they have brought about very little change in behaviour, with the number and complexity of cyber operations increasing rather than decreasing over time. More importantly, cyber operations are often chosen as a politically less-costly option: with no rockets, no tanks and no casualties, they do not attract the same levels of attention. Even though the norms and confidence-building measures (CBMs) proposed by the UN have been subsequently endorsed by the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), G7, G20 and the EU, the primary challenge with the existing approaches is their voluntary and non-binding nature, thus the absence of mechanisms to ensure compliance.10 Preventing cyber conflicts through voluntary measures can be likened to walking on water, particularly for the many sceptics of the idea; people wish to see proof first in order to believe in the potential benefits of results.

The belief in the almost mystical powers of norms and rules of responsible state behaviour as means to curtail states’ interests has only resulted in the emergence of more or less-formalised coalitions of like-minded states.

There are not many examples of how the described approaches have contributed to de-escalating or preventing a conflict in cyberspace, either. As a matter of fact, the focus on norms of responsible state behaviour and the lack of clarity about the interpretation of these norms by states, on the one hand, and the efforts to inject more accountability for the states that do not act in accordance with the agreed norms and rules, on the other hand, have only reinforced existing groupthink and divisions. In this sense, the belief in the almost mystical powers of norms and rules of responsible state behaviour as means to curtail states’ interests has only resulted in the emergence of more or less-formalised coalitions of like-minded states.

Another avenue explored, albeit not a standard conflict-prevention measure in cyberspace, has been coupling cyber-related negotiations with a broader political dialogue. This approach was deployed by several countries, in particular the US, China and Russia, who concluded bilateral cyber-specific agreements in an effort to de-escalate mounting political conflicts. For instance, against the background of growing accusations against China in 2015 concerning its economic cyber espionage operations in the US, then President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping reached a ‘common understanding’ on curbing such activities, whereby both leaders committed that their governments would not knowingly support the cyber theft of corporate secrets or business information. However, the hopes associated with this attempt have yet to be proved valid: just a year after the agreement was signed and amidst an unfolding trade war, the US accused China of breaching the agreed rules.

Effective regionalism

The above examples clearly indicate the limitations of existing approaches to preventing conflicts in cyberspace. But if hungry for results and concrete changes in states' behaviour, where can one expect effective solutions to come from?

Largely absent from the current discussions are references to conventional methods of preventive diplomacy. A term of art in conflict studies, preventive diplomacy refers to action taken to prevent disputes from arising or from intensifying into conflicts, and to limit the spread of conflicts when they occur. In international law, a corresponding term is the 'peaceful settlement of international disputes': the legal regime of peaceful/pacific settlement of (international) disputes is designed to make sure that reason is relied upon rather than use of force, other coercive means and, according to some authors, even countermeasures.11

Preventive diplomacy may take many forms, of which mediation, conciliation and negotiation are the most common. It can also occur in the form of good offices, facilitation, adjudication and arbitration, as well as fact-finding, confidence-building, early warning and preventive deployment.12 Employing diplomatic and peaceful methods, preventive diplomacy is, by default, non-coercive and non-escalatory. Actions are presumed to be preventive, rather than curative, and, obviously, are most effectively employed at an early stage of a dispute or crisis. At the moment, however, there are very few cases of research focused on the link between conventional conflict prevention mechanisms and cyberspace.13

Recognising that solving the problem of limited trust between the major powers requires a great amount of political will which is missing at this point in time, strengthening the regional structures for conflict prevention sounds like a more promising approach. Regional organisations born out of the need for building trust and strengthening cooperation among their members may hold the key to unlocking the stalemate at the global level. Most regional organisations are already actively shaping the developments in the cyber domain, including the development and operationalisation of norms and confidence-building measures.13 However, the link between this line of activity and other tools and mechanisms for conflict prevention is largely missing.

A more prominent involvement of regional organisations might offer an avenue to prevent escalation and stop cyber conflicts from breaking out. But this is not always straightforward. All regional organisations are rooted in their respective historical, geographic and cultural contexts, which impacts their mandates, capacities and the freedom to act. The OSCE, for instance, was the first to adopt a set of confidence-building measures that set the tone for the CBM conversation globally. However, pre-existing conflicts of a political or military nature complicate the implementation of those measures: the OSCE struggles with limited trust among its members, in particular in the aftermath of cyber-attacks against Ukraine, Georgia and Montenegro; the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum navigates the complex relationship between China and other countries in the region; and the Organisation of American States (OAS) tries to circumvent differences between the US and its other members like Cuba or Venezuela. In these circumstances, the perception of regional organisations as impartial intermediaries may be undermined.15 Nonetheless, the progress achieved within regional organisations to date – and despite the risks of duplication or conflicting outcomes – suggests that they provide a valid avenue. Further investment in ‘effective regionalism’ built on the merger of preventive diplomacy and cyber expertise in various regional organisations might offer a more effective way to deal with the current shortcomings of the ‘stability’ debate.

Testing Europe's DNA

As a leading regional organisation and a big supporter of integration processes around the world, can the EU lead the way? The answer is: it depends. In order to become a global leader in cyber conflict prevention, the EU needs to resolve two interrelated dilemmas.

First, can the EU credibly reconcile its potential role as an impartial mediator with a firmer approach aimed at strengthening accountability and enforcement in cyberspace, including through sanctions? The evidence to date suggests that through its actions the EU attempts to find a middle ground. Even though the cyber sanctions regime adopted in May 2019 aims to reinforce the EU’s cyber deterrence posture, so far, the Union has abstained from blacklisting any individuals or entities. Likewise, the declarations, statements and Council Conclusions condemning violations of norms of responsible state behaviour in cyberspace adopted in the past couple of years have stopped short of pointing fingers at any specific country. This skilful manoeuvring, however, may be difficult to maintain in cases of more aggressive attacks against individual member states or partner countries which result in louder calls for action at the EU level. For this to happen, however, the member states would need to acknowledge the EU’s role on issues such as the application of international law in cyberspace – a bridge too far for most European capitals.

Regional organisations born out of the need for building trust and strengthening cooperation among their members may hold the key to unlocking the stalemate at the global level.

Second, can the EU effectively combine all relevant instruments at its disposal? For this to materialise, two simultaneous adjustments will have to occur: a) cyber diplomacy will have to be mainstreamed into the EU’s foreign and security policy and b) conflict prevention16 will have to become the core business of the EU’s cyber diplomacy. The somehow artificial – and confusing – distinction between preventing conflicts, building stability in cyberspace, and promoting international cooperation illustrates the need for a more inclusive conversation in the Schuman area. For instance, while the current approach to preventing conflicts with the use of ICTs is built on strengthening cyber security and resilience and increasing awareness of businesses and citizens, among others, the commitment to the settlement of international disputes in cyberspace by peaceful means is a separate goal falling under the promotion of international cooperation.17 This approach, however, remains largely detached from the EU’s long-standing experience in fields of early warning and conflict prevention, which aim to ensure effective action ahead of crises.18 A more joined-up approach across different policy communities might help to address these inconsistencies.

While the first dilemma might be difficult to resolve – primarily due to the political nature of the question – the second might be relatively easy to address if the EU makes a better use of the existing instruments at its disposal, in particular the EU Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox. Merging certain elements of the Toolbox with the conventional instruments of conflict prevention might better project the EU’s image as a ‘global actor committed to the promotion of peace, democracy, human rights and sustainable development’.19 Most importantly, it might save lives in the case of cyber conflicts where there is a high probability of generating a kinetic response. So, how do we get there?

Early warning

Any contestation between political adversaries also manifests itself in cyberspace. Therefore, the risk that the use of cyber tools might result in a kinetic response – as was the case in the confrontation between the US and Iran in 2019 – needs to be urgently addressed. A better understanding of the root causes, motivations and cyber conflict dynamics will allow the EU to identify a range of available policy responses. Identifying actors ready to use cyber capabilities in a conflict might be a difficult task as such tools can be purchased at a relatively low cost on dark markets or directly from their producers and might be difficult to trace back due to the challenge of attribution. What is more feasible, however, is monitoring the movement of software and technologies across the world, especially to conflict-prone areas. Such a mechanism might be quite urgent given recent reports estimating that the global demand for offensive cyber systems – a market dominated by companies from the US, Israel and the European Union – is expected to rise by 39% to $9.7 billion by 2027.20 The sales of such technologies are already monitored by civil society organisations like Privacy International,21 and better tracking of the movement of software and technologies used could help in anticipating cyber-attacks and also offer a more nuanced understanding of the available means of warfare of different regimes and actors. Consequently, it might be useful to consider how cyber-related aspects could be integrated into existing mechanisms, such as the EU Conflict Early Warning System.

Mediation and dialogue

In an effort to demonstrate its commitment to the settlement of international disputes in cyberspace by peaceful means, the EU adopted the Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox in 2017, which enlists all measures within the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) catalogue at the service of cyber diplomacy. Nonetheless, most of the EU’s energy to date has been spent on giving prominence to measures with ‘more teeth’, in particular the cyber sanctions regime. While such measures are important for ensuring accountability in cyberspace, their rather antagonistic nature does not leave much room for engagement aimed at conflict prevention and de-escalation. What is more, the focus on accountability has brought limited results and even had negative side effects; it attracted additional criticism which saw the EU framed as an organisation with weak institutions and inadequate resources, and torn between the different approaches of the member states.

The EU could also use its economic and political power in cases in which bringing two sides to the negotiating table might prove particularly difficult due to existing animosities.

Strengthening preventive diplomacy in cyberspace through mediation and dialogue – a key component of the EU’s DNA – could further boost its credibility on the international stage. Yet such an approach would be resource-intensive and carries many political risks, which explains why it has been largely neglected. For instance, it would require political courage to establish dialogues on controversial cyber-related issues with countries such as Russia, Iran, or North Korea without any guarantees that they would come to the negotiating table in good faith. In addition, given that cyberspace is simply another theatre for geopolitical competition and military action during a conflict, it is not entirely certain if cyber elements could be successfully decoupled from the other root causes. At the same time, the EU would need to be more outspoken in instances when norms of responsible behaviour and international law are undermined by its allies and partners.

While there are many challenges to developing this new approach in parallel to the one focused on accountability, they should not be an excuse for not trying. The EU’s recent reaction to the 2019 cyber-attacks against Georgia might serve to illustrate this point: after several member states made statements attributing those attacks to Russia, the EU High Representative acting on behalf of the EU issued a declaration condemning the attacks and promised continued assistance to strengthen Georgia’s cyber resilience. He did not, however, point a finger at any particular state. Whether intended or not, the EU’s restraint in assigning the responsibility for cyber-attacks in this and other cases could open the door for it acting as a mediator between conflict parties. For instance, nothing prevents the High Representative in the future from offering his offices – or those of a dedicated EU Special Representative for International Cyberspace Policy22 – to assist conflicted sides in clarifying the circumstances of an attack and facilitating dialogue. The role of a mediator could include, among others, getting parties to agree on restraining malicious or aggressive cyber activity. The EU could also use its economic and political power in cases in which bringing two sides to the negotiating table might prove particularly difficult due to existing animosities.

State and societal resilience

Preventing conflicts and reducing the risks of escalation is not just a matter of discouraging attackers. It is also about developing adequate capacities to protect state institutions, businesses and citizens from attacks or helping them deal with the consequences. For instance, the capacity-building section of the 2015 UNGGE report flags the essential national assets and infrastructures that facilitate the prevention of unwanted developments in cyberspace: national computer emergency response teams, legal and administrative best practices, national plans and budgets or forensics.23 The logic of such an approach is simple: the better the capacity to prevent, respond and deal with the consequences of an attack, the lower the chances are of overreaction and an escalation of a conflict. In other words, strengthening resilience translates into better immunity of the state and societal fabric. Driven by this logic, the EU’s approach to conflict prevention has gradually embraced cyber capacity-building as one of its key elements, with projects and initiatives spanning the globe. The reliance on cyber capacity-building as a means to strengthen resilience also helps to shift the attention from the EU’s lack of advanced independent cyber capabilities towards tools and instruments in which the EU excels: developing strong regulatory frameworks and institution-building. In the future, such elements could also become part of the EU’s Security Sector Reform (SSR) endeavours under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) through new concepts such as Cyber Civilian Missions.24

Capabilities and capacity to act

Key to the EU’s efforts in cyber conflict prevention is its own capacity to employ the wide range of tools at its disposal in a coordinated way. That requires investing in the development of adequate capabilities at both human and institutional levels. For instance, in 2019 the European Parliament called for ‘the establishment, under the authority of the VP/HR, of an EU high-level advisory board on conflict prevention and mediation, with the aim of setting up a comprehensive pool of experienced senior political mediators and conflict prevention experts to make available political and technical expertise at short notice’.25 If implemented, such a pool could also include experts familiar with cyber-related de-escalation methods. In addition, the investment in conflict prevention will also require putting in place adequate knowledge management tools, including guidelines for actors engaged in mediation or dialogue, as well as collection of good practices and lessons learned. Given that attribution of cyber-attacks remains one of the biggest controversies, the development of an independent EU capacity – in cooperation with the EU member states who maintain the sole privilege of assigning responsibility – to assess the forensics and subsequently facilitate dialogue between the concerned parties would be one of the most useful capabilities to develop.

Inter-regional cooperation

Most current efforts are driven by the narrative about responsible behaviour in cyberspace. This gives the EU an opening to set the tone and lead international efforts on conflict prevention in cyberspace, in particular in its relations with other regional organisations such as the OSCE, ASEAN, the OAS, the League of Arab States (LAS), and the African Union (AU) with its regional communities. Recognising that each of these organisations works with different methods and objectives, the EU could use its existing dialogues – or establish new ones, when necessary – in order to better understand each region’s views on and mechanisms for dealing with cyber conflict. Since many of these organisations favour a more positive agenda in cyberspace focused on economic growth, innovation and development, the EU could use its established cooperation channels in those areas to push for such dialogues. More specifically, the EU and other regional organisations could host a series of workshops and seminars on early warning, root causes and risks to peace, mediation and societal resilience as means to prevent conflict in cyberspace. Already today, due to their knowledge of local and regional dynamics, regional actors are often the first ones to respond in mediation cases. Such improved information-sharing, cooperation and coordination between regional actors – with the support of the UN – would help to ensure the coherence and complementarity of efforts of actors involved in a specific mediation context.26 Given their extensive expertise, civil society and non-governmental organisations should be closely associated with these efforts.

Ultimately, what is urgently needed is a broader understanding that preventing conflicts in cyberspace is not a hypothetical problem without real-life consequences: virtual missiles might be quickly replaced by rolling tanks and exploding bombs. Sometimes, preventing conflicts in cyberspace might require a miracle. Most of the time, however, it will call for concrete mechanisms, resources and, of course, a hefty dose of political will. These, in turn, require courage and political leadership; preferably before the prophecies of a ‘cyber apocalypse’ come true.

References

* The authors would like to thank Katariina Mustasilta and Camino Kavanagh for their comments on an earlier draft of this Brief. Any mistakes or omissions are those of the authors alone.

1 Déclaration de Madame Florence Parly, ministre des armées, sur la stratégie cyber des armées, Paris, January 18, 2019, http://discours.vie-publique.fr/notices/193000118.html.

2 Dominic Nicholls, “Britain is ‘at war every day’ due to constant cyber attacks, Chief of the Defence Staff says”, The Daily Telegraph, September 29, 2019.

3 Mette Eilstrup-Sangiovanni “Why the World Needs an International Cyberwar Convention”, Philosophy and Technology, vol. 31, 2018, pp. 379–407.

4 Graham Evans and Jeffrey Newnham, Dictionary of International Relations, (London, Penguin, 1998); Robert Keohane and Joseph S. Nye Jr., Power and Interdependence, (Boston, Longman, 1997), p. 163.

5 ‘Unfriendly’ is an established term in international law. It means ‘a conduct (act or omission) of a subject of international law which inflicts a disadvantage, disregard or discourtesy on another subject of international law without violating any legal norm.

6 See: Eneken Tikk, Kristine Hovhannisyan, Mika Kerttunen and Mirva Salminen, “Cyber conflict factbook: effect-creating state-on-state cyber operations”, 2019, https://cpi.ee/news/; Brandon Valeriano and Ryan C. Maness, “The dynamics of cyber conflict between rival antagonists, 2001–11”, Journal of Peace Research, 2014, https://drryanmaness.wixsite.com/cyberconflict/cyber-conflict-dataset.

7 The United States, for instance, has adapted its response to malicious activities in cyberspace to address precisely the phenomenon of low-intensity/high-impact attacks through a new military doctrine of ‘persistent engagement’ and ‘defend forward’.

8 See: Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace, Advancing cyberstability, 2019, https://cyberstability.org/news/a-call-to-action-on-advancing-cyberstability-global-commission-launches-final-report/.

9 Since 1998, the debate about the peaceful use of ICTs has taken place in the First Committee on Disarmament. The current acquis that emerged as part of this process has been developed primarily under the umbrella of the UN Group of Governmental Experts established to deliver reports to the UN Secretary General. For more information about these processes, see: Digital Watch Observatory, https://dig.watch/processes/un-gge.

10 For an overview of international documents with the focus on norms, CBMs and international law, see: https://carnegieendowment.org/publications/interactive/cybernorms.

11 J. G. Merrills, International Dispute Settlement, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 563.

12 Boutros Boutros-Ghali, “An Agenda for Peace: preventive diplomacy, peacemaking and peacekeeping”, 1992.

13 A few groups conduct research on preventive diplomacy in cyberspace. For instance, Camino Kavanagh and Paul Cornish work on ‘Preventive diplomacy, ICT and inter-state conflict’ for the Federal Department of Foreign Affairs of Switzerland. Furthermore, the Mediation Support Group in the UN Department for Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (UN DPPA) and the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD) were tasked by the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres to develop a Toolkit on the role of digital technologies in armed conflict mediation.

14 Nicholas Ott and Anna-Maria Osula, “The Rise of the Regionals: How Regional Organisations Contribute to International Cyber Stability Negotiations at the United Nations Level,” in: S. Minárik, S. Alatalu, M. Biondi, M. Signoretti, I. Tolga, G. Visky (Eds.), 11th International Conference on Cyber Conflict: Silent battle, 2019, https://ccdcoe.org/uploads/2019/06/Art_18_The-Rise-of-the-Regionals.pdf.

15 OSCE, “Perspectives on the UN and regional organisations on preventive and quiet diplomacy, dialogue facilitation and mediation”, February, 2011, https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/PerspectivesonPreventiveandQuietDiplomacy_OSCE2011_0.pdf.

16 The EU external action for the prevention of conflicts is based on early identification of risk of violent conflict; improved understanding of the root causes, actors and dynamics of the (potential) conflict; enhanced identification of the range of options for EU action; and conflict-sensitive programming of external assistance. See: EEAS, Conflict Prevention, Peace building and Mediation, June 15, 2017.

17 Council of the European Union, Narrative paper on an open, free, stable and secure cyberspace in the context of international security, June 19, 2019.

18 European Parliament, Resolution on building EU capacity on conflict prevention and mediation, P8_TA(2019)0158, March 12, 2019.

19 Council of the European Union, Concept on Strengthening EU Mediation and Dialogue Capacities, November 10, 2009.

20 “How BAE sold cyber-surveillance tools to Arab states”, BBC News, June 15, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-40276568.

21 Privacy International, "Global Surveillance Industry", https://privacyinternational.org/explainer/1632/global-surveillance-industry.

22 Patryk Pawlak, "Rebooting the EU’s cyber diplomacy", EU Cyber Direct, November, 2019, https://eucyberdirect.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/rebooting-cyber-diplomacy-final-1.pdf.

23 United Nations, Group of Governmental Experts on Developments in the field of information and telecommunications in the context of international security, A/70/174, July 22, 2015.

24 Patryk Pawlak, “What if … the EU launched its first civilian cyber mission”, in Florence Gaub (ed.), What if … ? 14 futures for 2024, EUISS Chaillot Paper, No. 157, January, 2020, https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/CP_157.pdf.

25 European Parliament, op. cit.

26 United Nations, “Strengthening the role of mediation in the peaceful settlement of disputes, conflict prevention and resolution”, A/RES/68/303, July 31 2014.