You are here

Compliant or complicit? Security implications of the art market

Introduction

Illicit traffic in art and antiquities is by no means a new phenomenon, but its role in facilitating international insecurity is increasingly appreciable. As described in the EU’s 2020 Security Union Strategy, ‘trafficking in cultural goods has become one of the most lucrative criminal activities and a source of funding for terrorists as well as organised crime’ (1). The so-called Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), the radical jihadist group that has perpetrated or inspired some of the deadliest terrorist attacks on EU Member States in recent years, is known to have institutionalised this traffic as a source of fiscal income. Despite growing awareness of this fact, the wider ways in which the legitimate art market can be exploited for nefarious purposes such as sanctions evasion and money laundering are relatively understudied. Closer scrutiny of the art market – a grey economic arena that can utilise licit methods and legitimate actors to produce illicit money – is an important step in combating the major security threat that stems from the link between organised crime and terrorist groups (2). This Brief examines four ways in which the art market serves illicit groups: money laundering; financial accumulation in safe havens like freeports; commercialisation through galleries and auction houses of cultural objects tainted by illegality; and use of cultural objects as collateral and/or payment for drugs or weapons. It assesses the structural factors that facilitate these processes, particularly the market’s commercial, valuation, authentication, transport and legitimation dynamics.

Particularities of the market

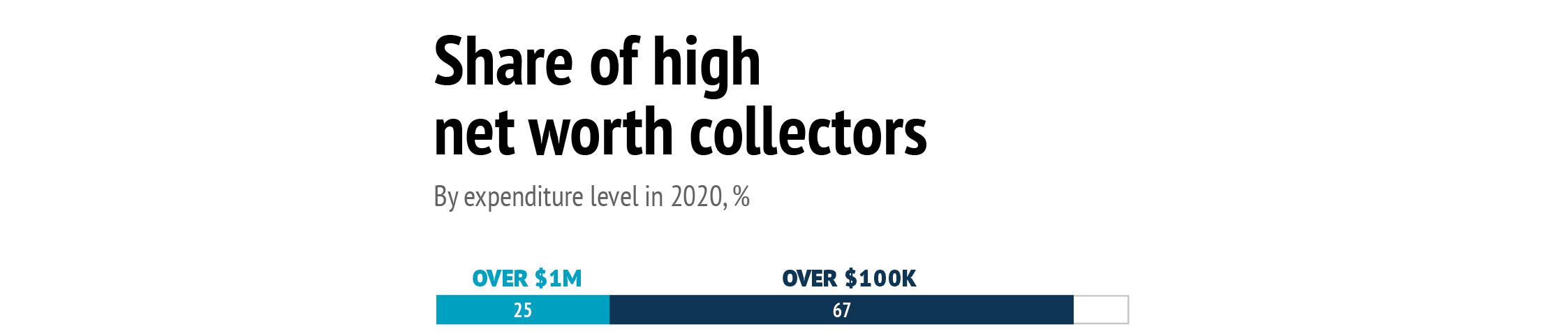

This section analyses the characteristics and conditions of the art market that are of interest to illicit groups, and which differentiate it from conventional and illicit markets. The art market boasts an opaque and complex set of interlocking aesthetic and economic systems, each made discrete by its own range of codes, conventions and relationships. Its relative informality and prized confidentiality hinder its transparency. The value of global sales in art and antiquities was an estimated USD 50.1 billion in 2020 (3), yet the art market is considered an anomaly in terms of the strict standards of transparency and regulation typically expected of multi-billion dollar international markets. The following outline of art market dynamics will reveal intermixing streams of legality and illegality, which make it particularly conducive to covert crime (4).

Current enforcement and evidential challenges weaken penal punishments for cultural objectsrelated crime.

Cultural objects (5) (unless they are forgeries) are not illegal per se but instead can be tainted by illegality, which is difficult to prove as it depends on origins and landmark dates. Unlike other highly priced assets, cultural objects rarely come to market with a complete ownership history. Instead, these items have ‘provenance’, which can be understood as a record of the object’s prior ‘social life’ and its wider cultural and social significance, such as its exhibition history. If an artwork has complete or near complete provenance, it will often be of greater value than would be the case if the documents attesting its provenance were missing (6). The lamentable corollary is that these provenance documents can be falsified. The documents accompanying antiquities often cite, for example, a private collection acquiring the object in 1969 (prior to the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property). Unlike the trade in illicit drugs or arms, which are typically sold on the black market, cultural objects can be more visibly advertised and sold because of the difficulty in proving the illicit acquisition of a particular object.

Linked to the question of documentary evidence is the importance of authenticity in the art market. Unlike gold, imitations of which are relatively easily identified, the modes of authentication in the art market are dually subject to legitimate mistake and manipulation. Independent art experts are not accredited by any specific training programmes nor are they regulated. The title connoisseur tends to accrue to an expert over the years they devote to the study of a particular artist. The potential for manipulation of this process is striking. There is an eagerness to hail forensic research as a ‘magic bullet’ for proving attribution, but technical analysis is itself left open to the varying interpretations of experts in that field (7). These specificities of the art market, and particularly its higher end, have resulted in the illicit trade in cultural objects often being facilitated by ‘professional enablers’. These can include restorers, scholars, collectors, museum curators, art storage personnel and auction houses.

Cultural objects are also portable by nature, meaning they can easily be moved across borders without attracting the attention of regulators (unlike money in a bank account). Antiquities can be disguised as souvenirs or ancient necklaces worn as regular jewellery, while larger cultural objects can be dismantled into smaller parts that would not raise the suspicion of a non-expert. A common evidential challenge in cases involving cultural objects is therefore the identification of an object as a valuable work of art or cultural property. Moreover, illegally excavated objects are unlikely to have been recorded anywhere, which complicates the identification process. A 2019 study showed that we have known origins for less than 2 % of antiquities sold on the German market, a figure that is further reduced to 0.4 % for Iraqi antiquities (8). Effective enforcement therefore requires the creation of dedicated police units, such as Italy’s patrimony police – the Carabinieri TPC (or ‘Carabinieri Art Squad’). The reliability of INTERPOL’s Stolen Art Database depends upon improved international cooperation as INTERPOL only receives annual information on cultural property theft from less than half of its States Parties (9). INTERPOL’s recently launched ID-Art app will hopefully empower a wider range of people to identify stolen artworks and cultural heritage crimes (10). Nonetheless, the current enforcement and evidential challenges weaken penal punishments for cultural objects-related crime.

The variability of art pricing is another lure for illicit actors – fine art is more subject to sharp escalations in price than other commodities because value can suddenly be boosted by subjective intangibles such as personal taste. The task of customs officials and law enforcement officers seeking to detect money laundering in a case of someone transferring money by overpaying another for a painting is severely complicated by the art market’s hard-to-quantify trends and inherent subjectivity. For example, if an ill-intentioned purchaser pays USD 35 million for a fine art masterpiece that they may have bought for USD 25 million just in order to move their illicit money, the ancillary profit could be reasoned away by subjective factors that affect value without raising suspicion. Moreover, the average customs official would struggle to differentiate an amateur painting from many high-value artworks such as those by Jean-Michel Basquiat, for example. This is unsurprising given that the art market itself tolerates or even invites the question ‘what is art?’ (11).

The resulting paucity of prosecutions and convictions is also linked to the fact that the majority of European art markets are subject to civil law, wherein the destruction and theft of artworks is criminally prosecuted but possession of stolen works is not (12). Civil law jurisdictions – such as France and Switzerland – protect bona fide purchasers over the interests of dispossessed owners (13). Common law jurisdictions, conversely, prefer the dispossessed owner from whom the artwork was stolen (14). In a move to harmonise international law pertaining to restitution claims, the 1995 International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT) Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects prescribed the stricter standard for purchasers of due diligence rather than good faith, but key market countries such as Belgium, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom have not ratified it stark contrast with other illicit trades, such as those in arms or drugs, wherein profit levels are high but so too is the risk of prosecution and incarceration. The art market is therefore one of low risk but high reward for organised criminals, terrorists and militias, as illustrated by various examples below.

Data: Art Basel & UBS, 2021

The relationship between the art market and international security

The Brief has traced how the characteristics and conditions of the ‘grey’ art market make it especially amenable to transnational crime. Terrorist involvement in the looting of cultural objects has been described as characterised by a ‘dual-exploitive approach’ because removing and trafficking cultural heritage both supports terrorists’ ideological objectives and generates income (16). For ISIS, the looting and sale of antiquities not only generated funds but also served to eliminate vestiges of the pre-Islamic period in Mesopotamia (17). For similar reasons, UNESCO has issued warnings about potential damage to and looting of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage following the Taliban’s recent takeover (18). In contrast, organised criminal groups are concerned with profit rather than ideological objectives (19).

Data: Art Basel & UBS, 2021

Money laundering, sanctions evasion

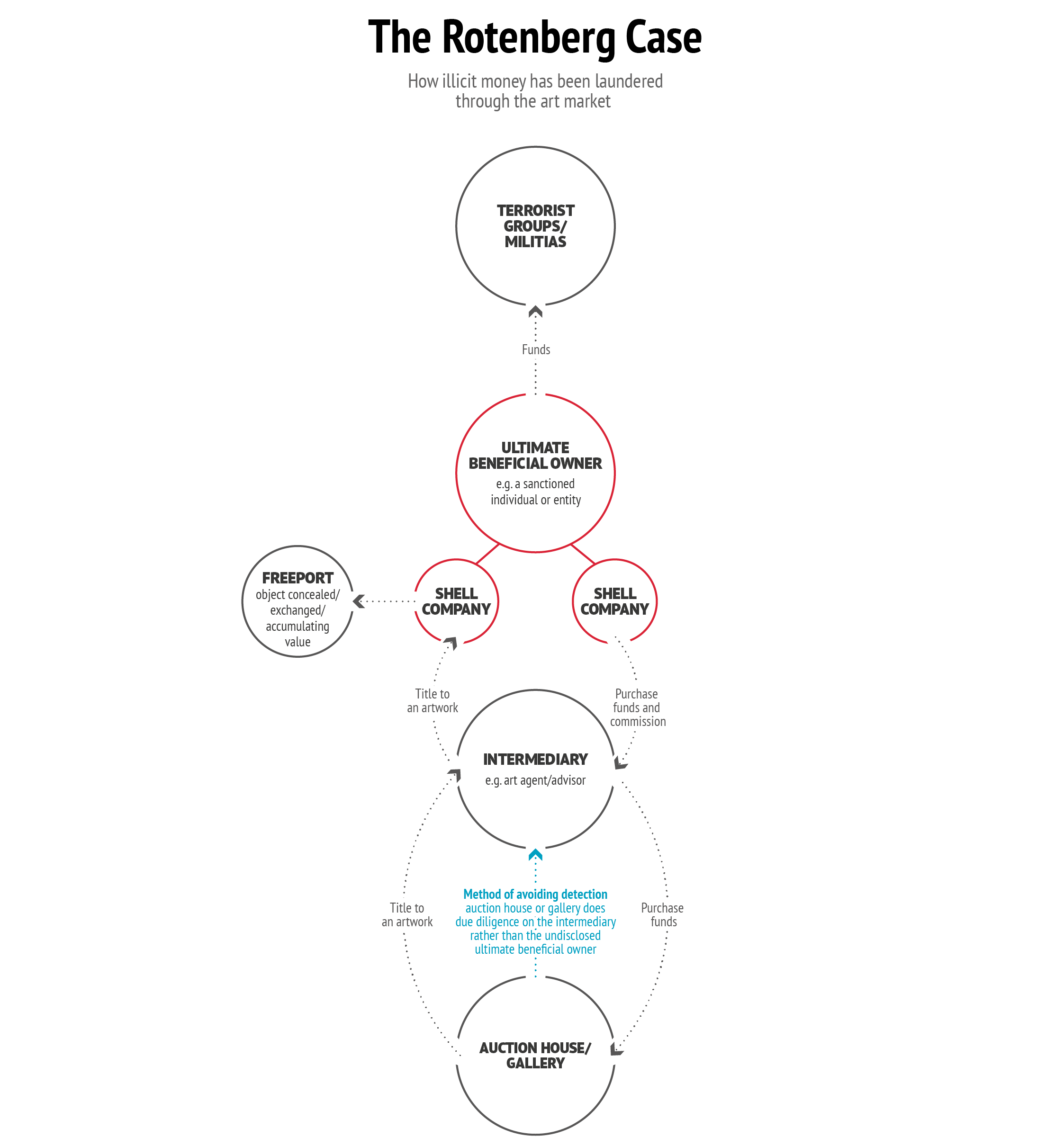

The connection between sanctions evasion and the art market has been described as ‘non-negligible due to certain features of the art market’ (20). Illicit actors can use shadowy corporate entities known as ‘shell companies’ and the norms of the art market to launder money and store it in cultural artefacts, which are less detectable than other assets.In 2019, a top Hizbullah financier was found to have circumvented United States’ sanctions through high-value art purchases.(21) Evidence of this art-related security risk was corroborated by a US Senate report on the art industry as part of an investigation into the effectiveness of sanctions imposed against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea. The report relates primarily to Russian oligarchs Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, who were sanctioned for their close ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin and significant profits that they derived from Crimea-related construction projects. The report maintains that the Rotenbergs continued to participate in US financial systems, post-sanctions, through high-value art transactions.(22)

The Rotenbergs had employed an art advisor to facilitate their purchase of artworks. Title to their artworks was subsequently assigned to shell companies, the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) of which is extremely difficult to trace, thus affording the Rotenbergs additional anonymity. By considering the art advisor as the principal rather than the agent in the transaction, auction houses and private dealers could conduct client due diligence on the advisor rather than on his undisclosed clients which included the sanctioned Rotenbergs. The auction houses and dealers therefore did not explicitly break any laws but rather facilitated the exploitation of market loopholes. Over USD 18 million in art purchased in the United States between March and November 2014 can be traced back to shell companies either funded or owned by the Rotenbergs. This demonstrates that the art market can be used to undermine sanctions, which are often considered a key tool for addressing foreign policy and security challenges.

The art market is one of low risk but high reward for organised criminals, terrorists and militias.

Many of the artworks purchased by the Rotenbergs were moved into storage in Germany without raising suspicion. Objects can sit undetected for years in storage, during which time provenance can be manipulated or assets exchanged beneath the radar of the authorities. Looted cultural objects from conflict zones are often ‘put on ice’ for a period in this way to help ensure that they are brought to market when the conflicts are no longer at the forefront of the public’s mind (23). The attractiveness of freeports, in particular, has grown as cultural objects have increasingly been portrayed as an asset class. Goods in freeports are technically considered ‘in transit’, which allows owners to defer customs and tax liabilities on their goods until they exit the freeport (24). Secrecy is prized in freeports, with almost anyone typically being able to bring in goods on another’s behalf without needing to disclose the UBO (25). Moreover, the registered value of a good often only depends on self-declaration, thus providing extensive room for over-or undervaluation (26).

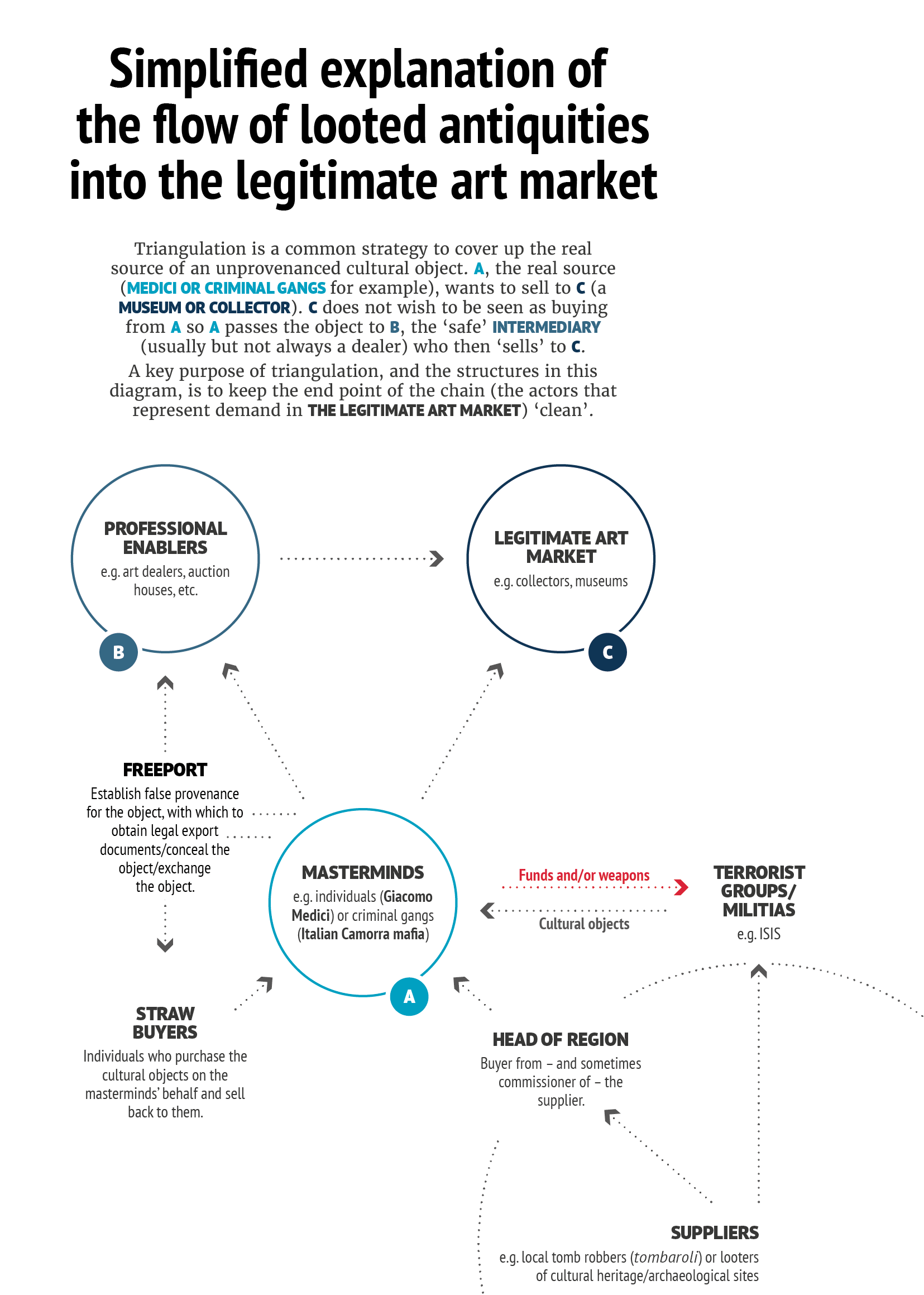

The amenability of freeports to transnational crime is exemplified by the Medici case, in which Swiss police discovered that Italian art dealer Giacomo Medici had been storing around 3 000 antiquities in Geneva freeport that had been looted in Italy and smuggled into Switzerland (27). Medici had used the privacy of the freeport to establish false provenance for the objects. He then obtained legal Swiss export documents for the items, which often wound up for sale on legitimate art markets in the United States and Europe. He then organised for ‘straw buyers’ to repurchase the items on his behalf and send them back to Switzerland. Many of the objects concerned were acquired by elite institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This complex process created provenance for the objects, effectively laundering them of their illicit origins and enabling Medici to market the works to collectors. The EU now treats freeports and art traders as ‘non-financial obliged entities’ (28). This requires freeport officials to inform the relevant financial intelligence units of any suspicious activity, conduct customer due diligence and to maintain records of UBOs. Switzerland has similarly amended legislation to enhance transparency within freeports (29). The role of freeports in potentially facilitating cultural objects-related crime is underlined by the United Kingdom’s announcement of the creation of eight new freeports as part of its post-Brexit trade strategy. The UK government has said that it does not intend to designate freeports for the purposes of High Value Luxury Storage, but stopped short of a firm commitment never to use the freeports for art and antiquities storage (30). This is particularly problematic given that the EU is a modest art market compared to the three largest markets – the United States, China and the United Kingdom – which make up 82% of total global sales by value and do not have similarly constraining legislation (31).

Funding terrorist groups and militias

Periods of armed conflict, insurgency, or terrorist activity make cultural resources significantly more vulnerable. This has been evidenced in the 1980s by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia profiting from the illicit trade in cultural objects as well as the Taliban and others doing so in Afghanistan in the 1990s (32). More recently, the Free Syrian Army dug up and sold cultural objects for funds to purchase weapons (33). ISIS is reported to have controlled looting and trafficking through a permit system, levying a 20 % khums tax on any proceeds (34). One analyst thus argues: ‘In the transition from target to tool, the importance of cultural property in international affairs has shifted from an issue of debate in foreign relations to a matter of practical consequence for international security’ (35).

The increasing connections being drawn between the illicit trade in cultural objects and terrorism financing were highlighted by UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 2347 (2017), which stated that ISIS and groups associated with al Qaeda ‘are generating income from engaging directly or indirectly in the illegal excavation and in the looting and smuggling of cultural property’ (36). The EU similarly adopted two ad hoc measures prohibiting trade in cultural goods with Iraq (37) and Syria (38) where there are reasonable grounds to suspect that the objects were removed without the consent of their legitimate owner or were removed in breach of national or international law. In 2018, the Civilian Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) Compact, which was established to strengthen the EU’s operational capacity to address persistent instability and transnational threats, rightly cited the preservation and protection of cultural heritage as an important dimension of security (39). UNSCR 2347 references an open question, namely to what extent terrorist groups are actively involved in the looting and trafficking of cultural objects or whether they merely facilitate the access of organised criminals. Reliable empirical evidence of the scale of terrorist groups’ profits from the illicit trade is also lacking (40).

The available evidence nonetheless confirms a relationship between the art market and terrorism financing: ‘It is a fundamental reality of the trade that some of the money paid in Europe for objects excavated in or traded through territory controlled by terrorist organisations must “trickle down” to the organisations involved’ (41). Those who justify inaction by querying the scale of the phenomenon compared to other illicit sources of finance (oil, drugs, weapons) risk losing sight of the reality that a single cultural object can attract a significant amount of money (42), whereas to quote one INTERPOL officer: ‘it only takes $10 to make a bomb’ (43).

The case for addressing the illicit trade in cultural objects is strengthened by research that reveals an intersection between different kinds of illicit trades (44). Pre-existing trafficking routes for drugs and arms have provided means for the illicit export of cultural objects, such as in Guatemala where antiquities have been found alongside marijuana shipments (45). The alertness of terrorist groups to different options for improving their finances as other sources of income dry up (46), coupled with the grey nature of the cultural objects trade compared to other trades, underlines the actual and potential relationship between the art market and security. Cultural objects have also been used as collateral and payment in drug deals, replacing diamonds and bullion in the latter case (47). Renowned artworks are rarely stolen for these purposes, as they would be too difficult to dispose of on the open market. Rather, artworks that are less easy to trace and identify are more readily used.Examples might include cuneiform tablets, which are mainly found in Iraq (trade from which is largely prohibited for protection purposes) but could also reasonably be from a neighbouring country such as Jordan (trade from which is permitted).

Manipulation of provenance to circumvent such restrictions is illustrated by the case of Jaume Bagot and Oriol Carreras Palomar. In 2018, they were arrested and charged for their alleged role in jihadi terrorist financing by laundering and selling trafficked antiquities from Libya (a conflict zone) and Egypt on the European art market (48). Most of the purchase invoices had mislabelled the cultural objects as being from Turkey or Egypt rather than Libya. Bagot, an art dealer, had been hailed as the ‘child prodigy of on ancient arts’ (49), which underlines both the value of reputation to the art market and the market’s unique ability to utilise licit methods and legitimate actors to produce illicit money. Reliable evidence also exists of arms-for-art trading rings. In 2016, the Italian Camorra mafia and ‘Ndrangheta organised crime group were found exchanging illegal arms for illicit antiquities from Libya with ISIS (50). ISIS is known to have received weapons such as Kalashnikov rifles in exchange for cultural objects, leading Italy’s then interior minister Angelino Alfano to conclude that ‘stolen artefacts […] contribute to the GDP of terror’ (51). Other areas deserving attention but that are not analysed in this Brief include online sales, art fraud and forgeries, especially given that the number of fake Syrian antiquities for sale on the internet has skyrocketed since the proclamation of the ISIS ‘caliphate’ (52).

Combating the illicit trade in cultural objects

The art market is far from a legal void. A 2015 report noted that, at the time, there were 167 laws and regulations that applied to the British art market (53). Rather than being unregulated (54), the art market is poorly regulated – the levels of due diligence undertaken in the art market are generally inconsistent. Legislative loopholes allow criminals to ‘port shop’ – that is to say, to intentionally enter the legitimate art market at its most vulnerable entry points. There is also a crucial lack of appropriate tools, namely a comprehensive stolen art database. While the multitude of options available for conducting due diligence – ranging from International Council of Museums (ICOM) red lists to private stolen art databases and looted art registers – permits flexibility in determining what level of research is merited for an item, such a range of options undermines the efficiency of any of them.

Rather than being unregulated, the art market is poorly regulated.

The art market is, for the reasons outlined, subject to increasing scrutiny in the EU, the United Kingdom and the United States. The EU has to date partially regulated the import of cultural goods such as art, collectibles, and antiquities through establishing a new common definition of cultural goods, a more rigorous certification system and a new licensing system for the import of archaeological objects (55). Doubts abound as to whether the EU regulation is fit for purpose given that it relies on an extensive amount of documentation about export dates and chains of ownership that this Brief has already established is untypical of the art market (56). In any case, the regulation will not be complete until an EU-wide electronic database comes into effect, which is due by 28 June 2025. The database’s effectiveness for crime detection will depend in part on greater investment in the specialised training of customs and police officials, given the art market’s seemingly innate potential for manipulation of provenance and misclassification of objects. Importantly, Great Britain opted post-Brexit not to adhere to the EU regulation, which may make its art market more attractive due to a reduced financial and administrative burden (57). While British dealers will remain subject to the rules when selling cultural objects in the EU, the interconnectedness of the global art market makes policy incoherence a concern for the EU (58).

Data: Europol, 2021

In 2018 and 2021, the EU and the United States respectively extended anti-money laundering reporting requirements for transactions to the art market, making due diligence compulsory whenever the value of a transaction or a series of related transactions is equal to or greater than €10 000 (59). The institutional discretion and secrecy of the art market, however, may hamper the effectiveness of these changes. Art lawyer Katie Wilson-Milne predicts a shift in transactions away from public auction towards private sales, an area which she describes as not having seen ‘a real cultural shift yet out of [the art market’s] kind of informality’ (60). As this Brief has argued, the art market is a compliant victim of the crime that affects it.

Policy recommendations

Art market norms have resulted in financial collaboration – unwitting or intentional – between art market participants, organised criminals and terrorists, with potentially deadly consequences for humanity. The following considerations should be borne in mind by policymakers as a way to manage this.

- Strengthen criminal sanctions for possession and sale of stolen cultural objects.

- Regulate the role of art experts to prevent them from legitimising false provenance. This is particularly important given that initial expert opinion will often serve as the basis for repeated sales by galleries or exhibitions in museums, through which purported legitimacy accrues.

- Create a Europol Cultural Objects Unit. Europol has, through Analysis Project Furtum and collaboration with the World Customs Organisation (WCO) and Interpol, made notable progress in recent years such as the Pandora operation which seized 56 400 cultural goods (61). The lack of a dedicated cultural objects unit, however, hinders a deeper understanding of the issue and ability to fight the crimes effectively.

References

* The author was affiliated with the Department of War Studies at King’s College London at the time of writing this Brief.

(1) European Commission, ‘Communication de la Commission relative à la stratégie de l’UE pour l’union de la sécurité’, 24 July 2020 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/FR/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0605&from=FR).

(2) European Parliament, ‘Report on findings and recommendations of the Special Committee on Terrorism’ (2018/2044(INI)), 21 November 2018 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2018-0374_EN.html) p. 8.

(3) McAndrew, C., ‘The Art Market 2021’, Art Basel & UBS Report, Art Basel, 2021, p.17.

(4) Mackenzie, S. and Yates, D., ‘What is grey about the “grey market" in antiquities?’ in Dewey, M. and Beckert, J. (eds), The Architecture of Illegal Markets: Towards an economic sociology of illegality in the economy, OUP, Oxford, 2017, pp.71-86.

(5) This Brief groups together antiquities and art using the term ‘cultural objects’ and defines the ‘art market’ as the market in cultural objects.

(6) Tompkins, A., Art Crime and its Prevention, Lund Humphries, London, 2016.

(7) O’Donnell, N., ‘The US art market must demonstrate its integrity – or further regulation is a certainty’, Apollo, 11 September 2020 (https://www.apollo-magazine.com/us-senate-report-anti-money-laundering-art-market/).

(8) Minister of State Michelle Müntefering, ‘The role of the European Union in the Protection and Enhancement of Cultural Heritage in conflict and crisis’, Federal Foreign Office, Germany, 12 November 2020 (https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/newsroom/news/muentefering-eu-cultural-heritage/2418012).

(9) Renold, M.A., ‘The legal and illegal trade in cultural property to and from Europe’, Joint European Commission-UNESCO Project, 20 March 2018, p. 8 (http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/CLT/images/630X300/Study_Prof_Renold_EN_02.pdf).

(10) INTERPOL, ‘INTERPOL launches app to better protect cultural heritage’, 6 May 2021 (https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2021/INTERPOL-launches-app-to-better-protect-cultural-heritage).

(11) Kennedy, M., ‘Call that art? No, Dan Flavin’s work is just simple light fittings, say EU experts’, The Guardian, 20 December 2010 (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2010/dec/20/art-dan-flavin-light-eu).

(12) Calvani, S., ‘Frequency and figures of organized crime in Art and Antiquities’, in Manacorda, S. (ed.), Organised Crime in Art and Antiquities, International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council of the United Nations, Milan, 2009, p. 31.

(13) As captured by the principle en fait de meubles, la possession vaut titre (in the case of moveable property possession is equivalent to title).

(14) As captured by nemo dat quod not habet (no one can transfer title on stolen property).

(15) State Parties to the Convention: https://www.unidroit.org/instruments/cultural-property/1995-convention/

(16) Danti, M.D., ‘Ground-based observations of cultural heritage incidents in Syria and Iraq’, Near Eastern Archaeology, Vol. 78, No. 3, 2015, 138.

(17) Jones, C., ‘Understanding ISIS’s destruction of antiquities as a rejection of nationalism’, Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies, Vol. 6, Nos 1-2, 2018, pp. 31-58.

(18) Villa, A., ‘Damage to Afghan cultural heritage could be long-lasting, UNESCO warns’, ARTnews, 20 August 2021 (https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/unesco-afghan-cultural-sites-taliban-1234602082/)

(19) Makarenko, T., ‘The crime-terror continuum: tracing the interplay between transnational organised crime and terrorism’, Global Crime, Vol. 6, No 1, 2004, pp.129-145.

(20) European Commission, ‘Illicit trade in cultural goods in Europe’, 12 July 2019, p.110 (https://op.europa.eu/fr/publication-detail/-/publication/d79a105a-a6aa-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search)

(21) US Department of Treasury, ‘Treasury designates prominent Lebanon and DRC-based Hizballah money launderers’, 13 December 2019 (https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm856)

(22) US Senate, ‘The Art Industry and U.S. Policies That Undermine Sanctions’, 2020 (https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2020-07-29%20PSI%20Staff%20Report%20-%20The%20Art%20Industry%20and%20U.S.%20Policies%20that%20Undermine%20Sanctions.pdf).

(23) ‘Illicit trade in cultural goods in Europe’, op.cit., p.103.

(24) European Parliamentary Research Service, ‘Money laundering and tax evasion risks in freeports’, October 2018, pp.5-6 (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/155721/EPRS_STUD_627114_Money%20laundering-FINAL.pdf).

(25) Ibid.

(26) Ibid.

(27) Cultural Heritage Resource, ‘Giacomo Medici’, Stanford Archaeology Center, 2017 (https://perma.cc/V85E-FLFR).

(28) Directive (EU) 2018/843 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive (EU) 2015/849 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32018L0843)

(29) ‘The legal and illegal trade in cultural property to and from Europe’, op.cit., p.14.

(30) Department for International Trade, ‘Freeports consultation: boosting trade, jobs and investment across the UK’, 7 October 2020 (https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/freeports-consultation).

(31) Art Basel and UBS, ‘The Global Art Market in 2020’ in The Art Market 2021, 2021 (https://theartmarket.foleon.com/artbasel/2021/the-global-art-market/).

(32) Nemeth, E., ‘Art and international security’, in Nemeth, E. (ed.), Cultural Security: Evaluating the power of culture in international affairs, Imperial College Press, London, 2015.

(33) Luck, T., ‘Syrian rebels loot artifacts to raise money for fight against Assad’, Washington Post, 12 February 2013 (https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/syrian-rebels-loot-artifacts-to-raise-money-for-fight-against-assad/2013/02/12/ae0cf01e-6ede-11e2-8b8d-e0b59a1b8e2a_story.html)

(34) Al-Azm, A., Al-Kuntar, S. and Daniels, B.I., ‘ISIS’s antiquities sideline’, New York Times, 2 September 2014 (https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/03/opinion/isis-antiquities-sideline.html).

(35) ‘Art and international security’, op.cit.

(36) Resolution (UN) of the Security Council of 24 March 2017 (https://www.undocs.org/S/RES/2347%20(2017).

(37) Council Regulation (EC) No 1210/2003 of 7 July 2003 concerning certain specific restrictions on economic and financial relations with Iraq and repealing Regulation (EC) No 2465/96 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A12016P%2FTXT).

(38) Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12016P%2FTXT).

(39) Council of the European Union, Conclusions of the Council and of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States, meeting within the Council, on the establishment of a Civilian CSDP Compact, 19 November 2018 (https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/37027/st14305-en18.pdf)

(40) Sargent, M. et al., Tracking and Disrupting the Illicit Antiquities Trade with Open Source Data, Rand Corporation, 2020 (https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2706.html).

(41) ‘Illicit trade in cultural goods in Europe’, op.cit., p.114.

(42) Capon, A. et al., ‘Assyrian relief sets second-highest price for ancient art at Christie’s New York despite Iraq’s repatriation call’, Antiques Trade Gazette, 1 November 2018 (https://www.antiquestradegazette.com/news/2018/assyrian-relief-sets-second-highest-price-for-ancient-art-at-christie-s-new-york-despite-iraq-s-repatriation-call/)

(43) Cavigneaux, E., ‘Defeating terrorism and saving art: fighting the same battle’, Groupe d’études géopolitiques, Working Paper 6, March 2021, p. 6.

(44) Calvani, S., ‘Frequency and figures of organized crime in Art and Antiquities’, in Manacorda, S. (ed.), Organised Crime in Art and Antiquities, International Scientific and Professional Advisory Council of the United Nations, Milan, 2009.

(45) Brodie, N., ‘The concept of due diligence and the antiquities trade’, Culture Without Context, Vol. 5, 1999, pp 12–15.

(46) Terrill, A., ‘Antiquities destruction and illicit sales as sources of ISIS funding and propaganda’, Letort Papers, US Army War College Press, Vol. 4, No 3, 2017, p. 24.

(47) Shelley L.I., Dirty Entanglements: Corruption, crime, and terrorism, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2014, p. 262.

(48) Loore, F., ‘Trafic d’art et terrorisme : L’enquête de Paris Match rebondit en Espagne’, Paris Match, 29 March 2018 (https://parismatch.be/actualites/132038/trafic-dart-et-terrorisme-lenquete-de-paris-match-rebondit-en-espagne).

(49) Ibid.

(50) Boucher, B., ‘Italian mafia helps arm ISIS with looted antiquities’, Artnet News, 18 October 2016 (https://news.artnet.com/market/italian-mafia-arms-isis-trading-art-707582).

(51) Maneker, M., ‘Those antiquities traded for arms go to Russia, China, Japan—then everywhere’, Art Market Monitor, 18 October 2016 (https://www.artmarketmonitor.com/2016/10/18/where-do-those-antiquities-traded-for-arms-go-russia-china-japan/).

(52) Bulos, N., ‘After Islamic State institutionalized looting in Syria, the market for fake antiquities is booming’, Los Angeles Times, 31 December 2016 (https://www.latimes.com/world/middleeast/la-fg-syria-fake-antiquities-2016-story.html).

(53) Art Business Conference, ‘Presentation by Pierre Valentin on “The myth of the unregulated art market”’, 3 September 2015 (https://www.theartbusinessconference.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Pierre.pdf).

(54) Ibid.

(55) European Parliament legislative resolution of 12 March 2019 on the proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the import of cultural goods (COM(2017)0375 – C8-0227/2017 – 2017/0158(COD)) (https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2019-0154_EN.html).

(56) Valentin, P. and Rogers, F., ‘Adoption of the Regulation on the Import of Cultural Goods: Start Preparing Now!’, Art@Law, 13 June 2019 (https://www.artatlaw.com/adoption-of-the-regulation-on-the-import-of-cultural-goods-start-preparing-now/).

(57) Dafoe, T., ‘In a win for UK antiquities dealers, Britain will abandon the EU’s strict regulations on importing cultural heritage now that it’s finalized Brexit’, Artnet News, 6 January 2021 (https://news.artnet.com/art-world/britain-abandons-eu-regulations-cultural-heritage-1935331).

(58) UK Blue Shield, ‘Press Release: UK Blue Shield concerned UK unprepared to prevent UK becoming a gateway for looted objects’, 24 May 2021 (https://ukblueshield.org.uk/eu-illicit-trafficking-regulations-in-the-uk/).

(59) Directive (EU) 2018/843 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive (EU) 2015/849 on the prevention of the use of the financial system for the purposes of money laundering or terrorist financing (https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32018L0843); Erskine, M., ‘Lifting the veil: art deals, the Bank Secrecy Act and the need for art fiduciaries’, Forbes, 28 June 2021, (https://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewerskine/2021/06/28/lifting-the-veil-art-deals-the-bank-secrecy-act-and-the-need-for-art-fiduciaries/?sh=78c109ee14b3).

(60) Art Law Podcast, ‘New and impending art world money laundering regulations’, 5 March 2021 (http://artlawpodcast.com/2021/03/05/new-and-impending-art-world-money-laundering-regulations/)

(61) Europol, ‘Press Release: Over 56 400 cultural goods seized and 67 arrests in action involving 31 countries’, 11 May 2021 (https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/over-56-400-cultural-goods-seized-and-67-arrests-in-action-involving-31-countries)