China was initially cautious in the development and application of blockchain technology. Among the technology’s best-known attributes are the relative anonymity and immutability of the information, as every blockchain transaction has a digital record and signature that can be identified, validated, stored and shared. This technology could therefore become a double-edged sword for the Communist Party of China (CPC), as it goes against the government’s efforts to censor content it considers sensitive and, in more general terms, efforts to assert its cyber-sovereignty.

However, after at first observing the emergence of blockchain technology with concern, China’s central government has increasingly seen it as an opportunity, as has been the case with most emerging technologies. Since the launch of the 13th five-year plan in 2016 and the release of the first White Paper on Blockchain Technology and Application Development by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology the same year, the CPC has increasingly considered that blockchain could become an economic, political and geopolitical asset for the country, if ‘guided’ well.

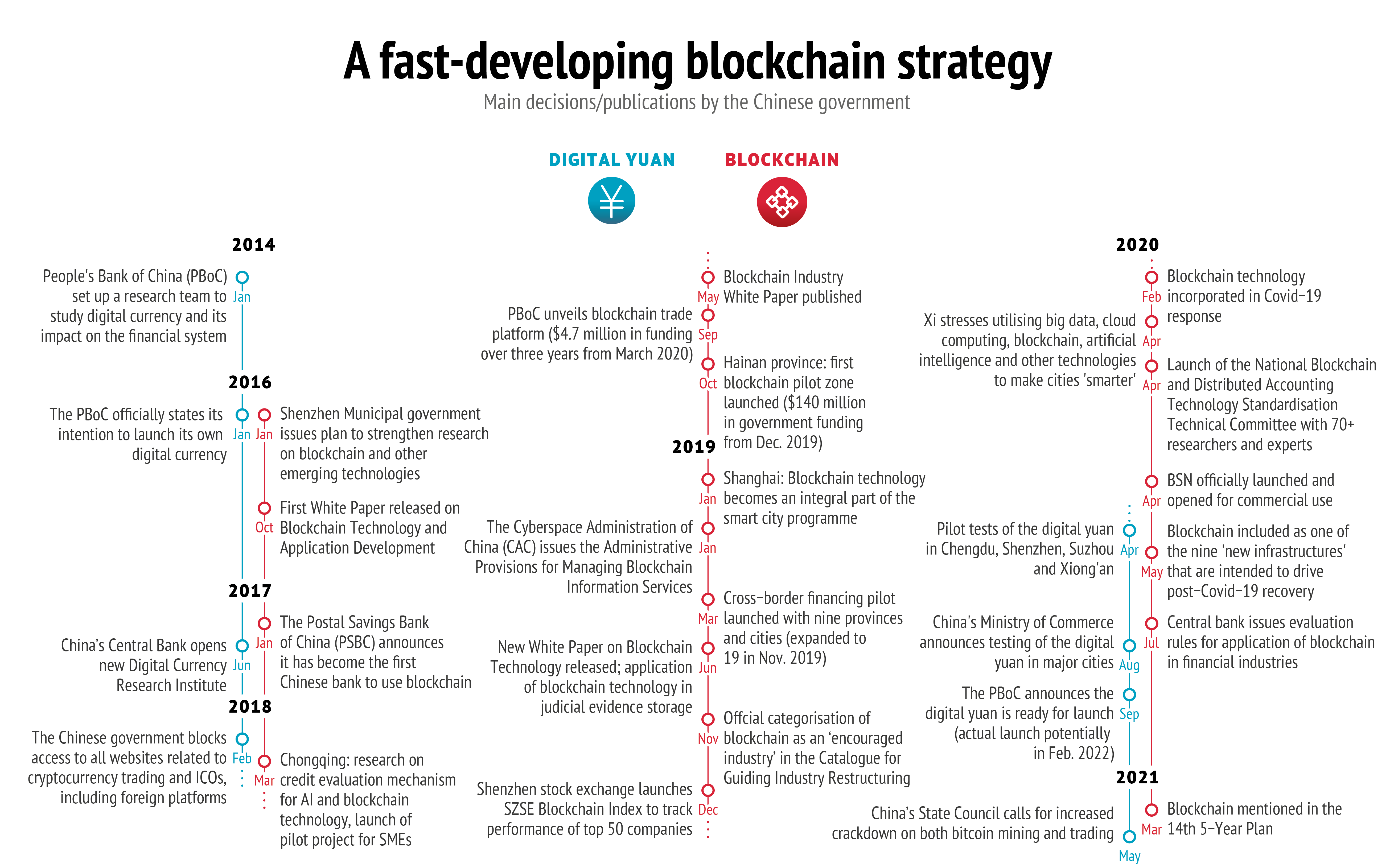

China has continued to shape its positioning on and conceptualisation of blockchain technology on a regular basis over the last 5 years: the China Blockchain Industry White Paper (1) was published in 2018, another White Paper entitled Blockchain Technology Application in Judicial Evidence Storage was published in 2019 (2) and the 14th five-year plan (2021–2025), released in March 2021, also refers to blockchain and cryptocurrency (see timeline diagram on page 7) (3).

China’s unique approach to blockchain is conditioned precisely by this paradox, stemming from the decentralised nature of the technology and the highly centralised nature of the Chinese political system. While blockchain technology is essentially decentralised, regulations in China have aimed to guarantee state control over its development and application.

As part of this dual policy, which is analysed in the first part of the Brief, the Chinese government has launched its own digital currency – the digital yuan. At the same time, it dislikes bitcoin, which relies on a truly decentralised type of blockchain. Although blockchain is best known for being the technology behind cryptocurrency, the Chinese government’s approach towards blockchain is very comprehensive, going far beyond cryptocurrencies. It promotes application of the technology in a variety of fields, ranging from energy conservation to urban management and law enforcement, and has strong ambitions to become the world leader in the field. In October 2019, China’s President Xi Jinping, speaking at a study session for members of the Politburo, declared that he wanted the country to be a ‘rule-maker’ on blockchain, suggesting that this technology will increasingly become a key arena in the country’s race against the United States for technological supremacy (4). Blockchain has become a fast-growing sector in China over the last two years.

But is China likely to succeed in the global promotion of an alternative form of blockchain? This Brief answers this question by analysing the development of different applications at national level, before and during the Covid-19 pandemic, but also the emergence of international cooperation on blockchain and cryptocurrency.

China's dual policy

Xi Jinping stated in October 2019 that ‘breakthroughs in key technologies should be accelerated to provide safe and controllable technological support for blockchain development and its application’ (5). In concrete terms, this has materialised, for instance, in the issuance in 2019 by the Cyberspace Administration of China of Administrative Provisions for Managing Blockchain Information Services, which forced blockchain platforms to collect users’ data and allowed authorities to access it (6). The rules came months after a student at Peking University used the blockchain platform Ethereum to avoid censorship and voice criticism about a case of sexual harassment and suicide from 1998. The case demonstrated the challenges that the technology could pose to government policies if tighter control was not implemented (7).

Although blockchain technology initially gained attention for its potential for decentralisation and evasion of state surveillance, the emergence of a tightly controlled, state-led configuration of blockchain in China now contrasts with the original libertarian image of the technology. For instance, EOS, a blockchain that is highly favoured by the government, is based on a model in which users vote for representatives and only these representatives can verify transactions and make decisions regarding system updates. All of the transactions and governance decisions in EOS are approved by only 21 main nodes (‘supernodes’), and 12 of these nodes are located in China – making it easier for the government to control them (8).

In 2019, China launched its own blockchain-based service network (BSN), which was subsequently established in April 2020, with the aim to reduce the cost of blockchain ‘development, deployment, operation and maintenance, interoperability and regulation’ (9). The BSN explicitly formulates the differences between two blockchain frameworks: permissionless – decentralised and transparent – and permissioned, in which all attributes are formulated by the owner. The former is difficult to operate in China because of the country’s regulations, according to the 2020 White Paper released by the network (10).

In concrete terms, the Chinese government is promoting a specific type of blockchain and cryptocurrency that is not open or fully decentralised. Intervention (including government intervention) can be exercised in case of emergency. If needed, data can be rolled back and transactions can be reversed. In extreme situations, the system can be shut down. The Chinese government is reshaping blockchain to such an extent that some may wonder if this technology can still be called blockchain. Beijing insists on using this term, which is already generating confusion and misunderstanding.

China’s approach towards blockchain is very comprehensive. First, in the banking sector, China has begun to test its potential at local level in the last few years, with the ultimate aims being to facilitate cross-border transactions and to make digital payments more secure (11). In October 2018, Hainan Province became China’s first ‘blockchain pilot zone’, and a blockchain security technology testing centre was established in Changsha (12). In March 2019, the government also developed a blockchain cross-border financing pilot platform, initially covering 19 provinces, which aims to improve transaction security and lower costs (13). The use of blockchain technology is also being tested by the 38 banks participating in the blockchain platform supervised by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC), which in 2020 secured USD 4.7 million in funding from the central government to support and develop this blockchain trade and finance platform over the next 3 years (14).

Second, the central government sees blockchain as a key pillar of the smart city infrastructures that are currently being built across China and as able to support a broad number of activities including road network management, public health, energy generation, communication, food safety and environmental pollution reduction. In 2019, blockchain became an integral part of Shanghai’s smart city programme, where it helps manage and store vast amounts of data generated by sensors. The government has also designed a blockchain-based identification system for smart cities to solve problems of data and application interoperability between them. Xi Jinping has urged that blockchain technology be integrated with other technologies used in urban environments, including artificial intelligence, big data and the Internet of Things (15). The government considers that 5G deployment could also benefit from the integration and security provided by blockchain technology. There are various ways in which these technologies support one another. For instance, a blockchain may be used to store large amounts of data that has aggregated rapidly thanks to the increased speed afforded by 5G technology. Already, blockchain-based cloud servers were used to store encrypted personal information during the Covid-19 crisis (16). This blend of blockchain with other technologies within the smart city ecosystem is likely to expand as China’s ambitious aspirations to take the lead on blockchain drive its equally ambitious aspirations to lead the smart city market.

Third, the Chinese government has leveraged the traceability and immutability offered by blockchain technology in the field of policing. Blockchain has already been used to verify and preserve electronic evidence (17), as well as store evidence collected during police investigations (18).

Fourth, the Chinese government has explored the use of blockchain for the dissemination of information and, in some instances, propaganda. For instance, blockchain-based platforms were used for the diffusion of official daily updates during the Covid-19 pandemic to ensure that the information provided was tamper-proof (19). The pandemic crisis provided a fertile testing ground for the expansion of blockchain applications: in only 2 weeks, over 20 applications based on blockchain were launched, including technology for online consultations and secure management of health records, a mini-programme on WeChat that can generate QR codes to enable residents to enter gated communities or the Alipay information platform to manage, allocate and donate relief supplies (20).

Fifth, the government is also exploring the use of blockchain to facilitate the management of government data and human resources. For instance, the People’s Liberation Army is testing blockchain technology to manage staff data, ‘boost performance’ and, in particular, provide soldiers with tokens they have earned, which can be used to collect rewards. In law enforcement and intelligence units, blockchain technology is already in use to prevent distortion or leaks (21).

Finally, the government is already using blockchain to gather evidence against dissidents online. For instance, blockchain-based platforms have been used to gather evidence on those defaming Chinese revolutionary martyrs via online platforms (22). Blockchain could also be used to ensure that data in the social credit system is always accessible and cannot be changed by unauthorised actors. This is not that far-fetched as, in December 2019, a seminar was organised in Beijing with the title ‘Blockchain technology helps China’s new social credit system’ (23).

All these developments underline two trends. First, the Chinese government is currently testing all possible applications of blockchain technology on its territory. This comprehensive testing provides Beijing with a comparative advantage over countries that anticipate potential applications but that are not yet testing them on the ground. The dual policy of the Chinese government remains experimental in many respects, but nonetheless the ‘work-in-progress’ approach provides the ability to fine-tune applications at a fast pace. Second, some of the blockchain applications tested by the government are shaped to support the one-party system and its surveillance and control functions. Beijing is developing a specific type of blockchain that is not only adapted to the authoritarian political system, but also has the capacity to strengthen it in some areas, such as policing and clamping down on dissent.

Blockchain and cryptocurrency: Not two sides of the same coin

As with blockchain technology more broadly, China sees digital currency as a double-edged sword, potentially threatening its financial sovereignty but offering opportunities to advance the growth of China’s digital economy, improve the efficiency of transactions, tackle illicit activities and facilitate online payments (24). Hence, despite having a sceptical and ambiguous stance towards some cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin or Facebook’s emerging cryptocurrency Diem (formerly known as Libra), China aims to take global leadership in the field of digital currencies, while ensuring state control and oversight.

China has historically been very active in both bitcoin mining and bitcoin trading, but the government has grown increasingly suspicious of bitcoin trading since 2013, and since 2017 it has introduced a series of regulatory measures to crack down on activities related to cryptocurrencies to insulate the financial system from the risks associated with them (25). Although Bitcoin trading has decreased sharply in recent years, China still has the world’s biggest mining pools (more than 60 % of the world’s mining capacities), far bigger than those of the United States and Russia (less than 10 % each) (26). This is in part because of the affordable price of electricity in China – cryptocurrency mining requires a lot of electricity, with powerful computers running non-stop.

But this state of affairs may evolve rapidly. In May 2021, China’s State Council called for an increased crackdown on both bitcoin mining and trading, shortly after three state-backed Chinese industrial associations vowed tougher restrictions on virtual currency trading (27). The Chinese authorities are likely to step up surveillance of bitcoin and the cryptocurrency market as a whole in the coming years.

China’s sceptical attitude towards cryptocurrencies comes at a time when it is developing its own state-backed digital currency. The digital yuan, officially known as the digital currency electronic payment (DCEP), is envisaged as a central bank digital currency (CBDC) and has the same legal status as the regular yuan, with its value tied to it (28). A CBDC echoes some of the features of bitcoin, as it enables consumers to use computerised code as money. However, this computer code is created and controlled by the central bank – not anonymous bitcoin miners. Other countries, including European ones – Sweden, for instance (29) – are in the process of exploring or developing their own CBDC, but they are behind China, which has already become the first country to test its digital currency.

The Covid-19 crisis gave renewed impetus to China’s CBDC. In May 2020, Chinese state-owned media reported that ‘design, standard-setting, R&D of the DCEP functions and joint tests have been basically completed’ (30), and a one-week trial was carried out during the 2021 Lunar New Year. A nationwide roll-out of the virtual currency is expected in time for the Winter Olympics in Beijing in February 2022, but this timeframe has yet to be confirmed.

The PBoC, which began to study digital currency in 2014, will remain the primary supervisor of the process, but DCEP is also likely to be integrated with Ant Group’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Pay, which currently control 90 % of digital payments in China (31). Although many details about its implementation are not yet clear, DCEP is expected to replace only part of the cash in circulation. Current channels of money supply will not be altered in the short term.

Still, the digital currency has the potential to substantially increase the central bank’s oversight of transactions. According to the 2019 regulation of the Cyberspace Administration of China, the banks and electronic payment companies that will distribute the new digital currency already require users to authenticate their real names as well as national identification card numbers, and the central bank will be able to view data on transactions (32). Hence, China’s digital currency will substantially increase control over the population, whose financial dealings will be easily trackable by the central authorities. They will no longer need to obtain customer information from payment companies to monitor citizens’ transactions.

China's international ambitions

Several developments described above may have international repercussions, as Beijing has placed blockchain on its diplomatic agenda since 2018 and promoted cooperation in the field through existing forums. For instance, blockchain was addressed at the 2019 China-Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) Cooperation Forum and the possibility of establishing a China–CEEC blockchain centre of excellence was mentioned in the Dubrovnik Guidelines for Cooperation (33). A first China–CEEC Blockchain Summit was held in Slovakia in December 2019 (34). Blockchain has also been addressed as part of other summits and initiatives, including the ‘Belt and Road Initiative’(BRI) (35), the 2018 Boao Forum for Asia (36) and the second China International Import Expo in 2019 (37), as well as in bilateral meetings (38).

In a context of intensifying trade tensions and technological rivalry between Washington and Beijing, blacklisting is likely to spill over to blockchain, further fragmenting the blockchain industry, which has emerged in a rather disparate way. Many applications of blockchain (urban governance, logistics, supply chain management, customs and cross-border trade) could be hindered because of interoperability concerns (39). In any case, China’s ambition to lead the world in blockchain development is posing two key geopolitical challenges: one related to China’s development of blockchain as a whole, and one related to the development of the digital yuan more specifically.

Blockchain: geopolitical, industrial and normative implications

Beijing has strengthened research capabilities in the field of blockchain over the last 5 years in part with the aim of shaping blockchain standards. China leads the international research group on the Internet of Things and blockchain standardisation, created in 2018 (40). In addition, in the first half of 2019, China announced a total of 3 547 patents on blockchain technologies, more than in the whole of 2018 and accounting for over half of the world’s total (41). In October 2019, Xi Jinping stressed ‘the importance of stepping up research on the standardization of blockchain to increase China’s influence and rule-making power in the global arena.’ (42)

The BSN mentioned above is China’s most ambitious and comprehensive project on shaping blockchain at the global level. While the BSN is largely driven by economic and commercial concerns, it certainly has geopolitical ramifications. First, the BSN is envisaged as an international project, and as a network used to operate different types of blockchain applications. So far, the overwhelming majority of nodes are located within China (more than 100); there are eight overseas city nodes, distributed over six continents (43). Second, although the BSN allows organisations to establish their own nodes, at the top of the pyramid it will be managed by a consortium formed by Chinese companies and a state government agency. Third, the BSN could support further deployment of China’s BRI,

and particularly the ‘Digital silk road’ and Beijing’s e-commerce ambitions. Fourth, through its BSN project, China is planning to pilot integration with global central bank digital currencies. In particular, it intends to build a universal digital payment network (UDPN) based on CBDCs of various countries as part of its 2021 roadmap. With the UDPN, the BSN aims to enable a standardised digital currency transfer method and payment procedure, and increase cross-currency settlement. The beta version of the UDPN is expected to launch in the second half of 2021, and its full development is planned to be completed within 5 years (44). The list of cooperating countries has not yet been disclosed, but in February 2021 China co-founded a project dubbed the ‘Multiple Central Bank Digital Currency Bridge’ along with the Bank of Thailand, the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority with the aim to explore the use of CBDCs in several cross-border payment scenarios (45).

Internationally, various protocols are competing for adoption but none has gained prevalence so far. Through the BSN, China offers infrastructure to other countries and could in turn gain some first-mover advantages (46). If the BSN gains international appeal, it could push China to the forefront of blockchain rule-making.

However, it is unlikely that the BSN will exert universal appeal. US-China technological tensions are likely to have an impact. For instance, companies such as China Mobile, whose operations are banned in the United States because of security concerns, are involved in the BSN. Still, China is well ahead of the curve in terms of blockchain conceptualisation and promotion, and countries that are not opposed to Chinese technologies (in parts of South-East Asia, Africa and Latin America, but also the EU’s neighbourhood) may remain open to China’s blockchain proposals in the coming years.

Digital yuan: Geo-economic implications

Theoretically, the release of the digital yuan could sustain China’s efforts to internationalise its currency and, in the long term, challenge the supremacy of the US dollar and the SWIFT system. But any assessment of the potential of the digital yuan to accomplish this should be cautious given the current centrality of the US financial system. To date, the yuan, and its forthcoming digital version, have not challenged the US dollar. China’s currency makes up about 2 % of global foreign exchange reserves, compared with nearly 60 % for the US dollar (47). Technical developments alone will not be enough to accelerate the internationalisation of the yuan; policy decisions will also be necessary, as China maintains a strict regime of capital controls.

Still, the development of the digital yuan is raising concerns in the US and has intensified the debate there on launching a digital dollar – in particular since Janet Yellen was appointed as Secretary of the Treasury in January 2021 – but this would still take time to take shape.

With the launch of the DCEP, China is expecting to enhance the renminbi’s global standing (48) and progressively convince a number of countries to use its digital currency for cross-border exchanges. The distribution of the digital yuan could be advanced through trade and infrastructure deals alongside China’s BRI, for instance by requiring countries to repay their loans in this currency. Other forums could be receptive to using the digital yuan for international settlements – for instance, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation or the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) could be candidates for this experiment. In 2019, the BRICS countries began cooperating on this at the proposal of Russia, with the objective of reducing dependency on the US dollar and facilitating trade (49). In addition, it might be easier for China to promote the adoption of the digital yuan in countries where Alipay and WeChat Pay are more advanced. Finally, as has occurred with other technologies, Beijing could leverage its consolidated expertise to promote its digital currency in other countries, through training and technical assistance. Other governments, keen to evade US oversight, may be eager to take advantage of this.

In concrete terms, some sanctioned countries could avoid having to use the US dollar for transactions, therefore impairing the ability of the United States to monitor critical revenue streams to such countries and to enforce economic sanctions (50). Besides undermining Washington’s ability to resort to sanctions as a means of deterrence, the United States would lose overall oversight of funding of underground activities (such as terrorism or missile development) if such payments are not made under its system.

On the other hand, China’s increased ability to monitor financial activity could raise serious concerns regarding privacy. The digital yuan could potentially be leveraged to monitor political dissidents beyond its borders. Washington would be likely to seek to retain its oversight and China would be likely to enhance its monitoring capability. This could materialise in efforts to ban each other’s systems or discourage their use (e.g. a Huawei 5G-like scenario of exerting pressure for its adoption/rejection) and in the issue of the interoperability/convertibility of digital currencies.

Conclusions

Blockchain is an emerging technology that remains largely in the experimentation phase, with its full potential not yet unleashed. Hence, it is still too early to accurately evaluate China’s blockchain strategy. However, blockchain is already becoming an arena for competition between countries, especially between the United States and China. In addition to the emerging geopolitical and geo-economic challenges identified in this Brief, political challenges are also emerging with the development of blockchain: because truly decentralised blockchain is challenging the ability of authoritarian governments to maintain tight control over their populations, several of these governments – especially China’s – are investing massively in blockchain to reshape it in a way that is compatible with the one-party system.

The ambition is that ‘blockchain with Chinese characteristics’ could even reinforce the CPC’s control over the daily life of the national population. And the development of the digital yuan itself may reinforce the government’s surveillance capabilities at both micro- and macroeconomic levels (control of transactions and overall consumption, but also inflation). To some extent, China could emerge as a model for other undemocratic countries in developing blockchain with surveillance and censorship capabilities (51).

China’s approach to blockchain is growing more confident and unequivocal, whereas other countries have been more uncertain about endorsing this technology. The EU has had some degree of ambition internationally. Blockchain has also been publicly recognised by European institutions as an emerging technology to invest in. Key initiatives at the EU level have included the decision in 2018 by 21 EU Member States and Norway to set up the European Blockchain Partnership to enable cooperation on the creation of a European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI). In parallel, an EU Blockchain Observatory and Forum was set up in 2018 with the aim of accelerating blockchain innovation (52). In 2019, the European Commission launched the International Blockchain Association, comprising 105 organisations from the public and private sectors. The coronavirus crisis has also been seen as giving an impetus to the European Commission’s digital agenda. (53) Elements of an EU blockchain strategy are emerging, with strong consideration of the issues around standards and interoperability (54).

However, although blockchain has not been absent from the European debate, over the last 3 years China has largely outpaced the EU not only on blockchain investment (55) but also on the concrete implementation and testing of the technology.

To address this gap, and because the blockchain structure and applications reshaped by the Chinese government have lost fundamental elements of the original technology, it would be timely if the EU could fine-tune its own conception of blockchain, and potentially reject the use of the term ‘blockchain’ to designate non-transparent and centrally controlled systems. Clarification of what blockchain is and means in EU terms would help Member States develop on their territories a type of blockchain that is fully compatible with their interests and values, and identify blockchain networks that could represent threats to their national sovereignty. It would also help reinforce cooperation with various (extra-European) central banks for the bridging and joint development of CBDC initiatives among countries that share a similar conception of blockchain.

To date, the EU seems more focused on the private and financial dimensions of blockchain applications and less so on its potential for use in governance than China. The launch of the EBSI – a network of distributed nodes across the EU that will deliver cross-border public services, which is planned to come into production in 2021 – is a first step but it would gain from being developed more ambitiously and comprehensively in the coming years. The EU would also gain from fully integrating blockchain in its connectivity agenda, as the technology provides a network that has the ability to reinforce interoperability between different cities and regions on European territory, as well as between the EU and various foreign partners sharing similar approaches towards the network.

The European Commission is already taking an active role in the shaping of blockchain standards, but the standards landscape is complex, fragmented and competitive – with China also being active in promoting its own standards. In this context, the EU could reinforce its position as a standard-setter in the field, especially through active participation in supranational and industry bodies.

Within Europe, the European Central Bank will decide whether to launch a digital euro project towards the end of 2021, with a formal launch still perhaps being around 5 years away (56). If the digital euro project is adopted, the implementation process would need to be fast-paced, with the aim being to develop a digital currency that is strong and compatible with a democratic context – addressing data, privacy and liability issues (maintaining, for instance, the same level of anonymity that is associated with cash).

In broader terms, the EU would also gain from addressing the governance potential of the technology, considering that blockchain can either support or undermine a democratic system depending on how it is developed. Like the internet, blockchain raises a myriad of political challenges and is already emerging as a battlefield for competition between different types of governance systems.

References

* The author would like to thank Cristina de Esperanza Picardo and Sophie Reiss, trainees for Asia at the EUISS, for their helpful research assistance, as well as Raphaël Bloch, journalist at L’Express, for his useful feedback on this Brief.

(1) Seconded European Standardization Expert for China (SESEC), ‘China blockchain policies and standardization’, 20 February 2020 (https://www.sesec. eu/china-blockchain-policies-and-standardization/); ‘White paper released on China’s blockchain technology’, People’s Daily, 21 May 2018 (http://en.people.cn/ n3/2018/0521/c90000-9462432.html).

(2) ‘E-evidence preservation potential key area for blockchain use: white paper’, People’s Daily, 21 June 2019 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/0621/c90000-9590289. html).

(3) ‘Fourteenth Five-Year Plan for the National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China and the Outline of Long-Term Goals for 2035’ (中华人民共和国国民经济和社会发展第十四个五年规划和2035年远景目标纲要), March 2021 (https://www.guancha.cn/politics/2021_03_13_583945.shtml)

(4) Cai, J., ‘Will the China of tomorrow run on the technology behind bitcoin?’, South China Morning Post, 2 December 2019 (https://www.scmp.com/news/ china/politics/article/3040132/will-china-tomorrow-run-technology-behind- bitcoin).

(5) Xinhua, ‘Xi stresses development, application of blockchain technology, 25 October 2019. (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-10/25/c_138503254. htm).

(6) Reuters, ‘China imposes blockchain rules to enable ‘orderly development’, 10 January 2019 (https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-china-blockchain/china- imposes-blockchain-rules-to-enable-orderly-development-idUKKCN1P41FX).

(7) Wade, S., ‘Translation: open letter on PKU #MeToo case’, China Digital Times, 23 April 2018 (https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2018/04/translation-open-letter- on-peking-university-metoo-case/).

(8) ‘Chinese internet users turn to the blockchain’, op.cit.

(9) Xinhua, ‘Commercial use of China’s blockchain-based service network kicks off’, 26 April 2020.

(10) BSN Development Association, Blockchain-based Service Network (BSN) Introductory White Paper, 5 February 2020.

(11) ‘SAFE expands pilot blockchain platform’, People’s Daily, 12 November 2019 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/1112/c90000-9631407.html).

(12) ‘China’s first blockchain security technology testing center established in Changsha’, People’s Daily, 29 October 2018 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2018/1029/ c313938-9512798.html).

(13) Reuters, ‘China to expand blockchain pilot, study forex reforms for cryptocurrency: regulator’, 24 December 2019 (https://www.reuters.com/article/ us-china-forex-blockchain/china-to-expand-blockchain-pilot-study-forex- reforms-for-cryptocurrency-regulator-idUSKBN1YS0GR/).

(14) Xinhua, ‘China sees more banks using blockchain platform: central bank’, 21 February 2020 (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-02/21/c_138806484.htm); Haig, S., ‘China’s central bank to inject $4.7M into blockchain trade platform’, Cointelegraph, 9 March 2020 (https://cointelegraph. com/news/chinas-central-bank-to-inject-47m-into-blockchain-trade- platform).

(15) ‘Xi stresses development, application of blockchain technology’, op.cit.; ‘China launches blockchain-based smart city identification system’, Global Times, 4 November 2019 (http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1168878.shtml).

(16) ‘Blockchain technology improves coronavirus response’, People’s Daily, 17 February 2010 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2020/0217/c90000-9658792.html).

(17) ‘Internet court makes case hearing efficient’, People’s Daily, 8 January 2020 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2020/0108/c90000-9647150.html); ‘E-evidence preservation potential key area for blockchain use: white paper’ op.cit.

(18) Zhao, W., ‘China’s security ministry touts blockchain for evidence storage’, Coindesk, 9 May 2018 (https://www.coindesk.com/chinas-police-ministry- touts-blockchain-for-secure-evidence-storage).

(19) ‘Blockchain technology improves coronavirus response’, op.cit.

(20) Ibid.; ‘SF Express deploys blockchain, big data to track medical good supply’, Global Times, 30 March 2020 (http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1184152. shtml).

(21) Cai, J., ‘Will the China of tomorrow run on the technology behind bitcoin?’, South China Morning Post, 2 December 2019 (https://www.scmp.com/news/ china/politics/article/3040132/will-china-tomorrow-run-technology-behind- bitcoin); ‘Blockchain incorporated in evidence gathering in E China’, People’s Daily, 16 November 2019 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/1116/c90000-9632885. html).

(22) The Heroes and Martyrs Protection Law of China (2018) ‘promotes patriotism and socialist core values, bans activities that defame heroes and martyrs or distort and diminish their deeds. It stresses that those who violate their rights of name, portrait, reputation, and honor will be punished’: ‘Law to protect heroes’ honor to take effect May 1’, China Daily, 30 April 2018 (https://www.chinadaily. com.cn/a/201804/30/WS5ae7263aa3105cdcf651b4e1.html).

(23) Zhang, R., ‘Experts discuss building blockchain and new social credit system’, China.org.cn, 22 January 2020 (http://www.china.org.cn/business/2020-01/22/ content_75640228.htm).

(24) Xinhua, ‘No timetable to launch digital currency: China central bank governor’, 26 May 2020 (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020- 05/26/c_139089462.htm).

(25) Gloudeman, L., ‘Decoding cryptocurrency in China’, Rhodium Group, 5 July 2017 (https://rhg.com/research/decoding-cryptocurrency-in-china/).

(26) Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance, University of Cambridge, ‘Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index – Bitcoin mining map’, April 2020 (https://cbeci.org/mining_map).

(27) Xinhua, ‘China doubles down efforts on virtual currency regulation’, 25 May 2021 (http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-05/25/c_139967314.htm).

(28) Baker, P., ‘Unlike Libra, digital yuan will not need currency reserve to support value: PBOC official’, Coindesk, 23 December 2019 (https://www.coindesk.com/ unlike-libra-digital-yuan-will-not-need-currency-reserves-to-support- value-pboc-official).

(29) Fulton, C., ‘Sweden starts testing world’s first central bank digital currency’, Reuters, 20 February 2020 (https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cenbank- digital-sweden/sweden-starts-testing-worlds-first-central-bank-digital- currency-idUSKBN20E26G).

(30) ‘No timetable to launch digital currency: China central bank governor’, op.cit.

(31) Kapron, Z., ‘China’s central bank digital currency will strengthen Alipay and WeChat Pay, not replace them’, Forbes, 24 May 2020 (https://www.forbes.com/ sites/zennonkapron/2020/05/24/chinas-central-bank-digital-currency-will- strengthen-alipay-and-wechat-pay-not-replace-them/#9196a2a6b699).

(32) Zhong, R., ‘China’s cryptocurrency plan has a powerful partner: Big Brother’, New York Times, 18 October 2019 (https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/18/ technology/china-cryptocurrency-facebook-libra.html); Feng, Y., ‘China, CEEC aim for more cooperation at expo’, People’s Daily, 17 June 2019 (http://en.people. cn/n3/2019/0617/c90000-9588582.html).

(33) ‘Full text of the Dubrovnik Guidelines for Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries’, People’s Daily, 14 April 2019 (http:// en.people.cn/n3/2019/0414/c90000-9566558.html).

(34) Secretariat for Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries, ‘First China-CEE Blockchain Summit held in Slovakia’, 19 December 2019 (http://www.china-ceec.org/eng/zdogjhz_1/t1727022.htm).

(35) Jao, N., ‘China strengthens blockchain cooperation with BRI countries’, Technode, 5 December 2019 (https://technode.com/2019/12/05/china-unveils- initiatives-to-strengthen-blockchain-cooperation-with-bri-countries/).

(36) ‘Boao Forum for Asia to highlight reform, opening up, innovation’, People’s Daily, 26 January 2018 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2018/0126/c90000-9419960. html).

(37) ‘2nd CIIE sets to accelerate China’s higher-end consumption, greener growth’, People’s Daily, 31 July 2019 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/0731/c90000- 9601929.html).

(38) ‘China, Kazakhstan to expand cooperation in multiple areas, boost ties’, People’s Daily, 5 November 2019 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/1105/c90000- 9629412.html).

(39) O’Neal, S., ‘Blockchain interoperability, explained’, Cointelegraph, 5 September 2019 (https://cointelegraph.com/explained/blockchain- interoperability-explained).

(40) Arcesati, R., ‘Chinese tech standards put the screws on European companies’, Mercator Institute for China Studies, 29 January 2019 (https://www.merics.org/ en/blog/chinese-tech-standards-put-screws-european-companies).

(41) ‘A review of major Chinese scientific and technological breakthroughs in 2019’, People’s Daily, 31 December 2019 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/1231/ c90000-9645225.html).

(42) ‘Xi stresses development, application of blockchain technology’, op.cit.

(43) Musharaff, M., ‘China launches blockchain-based service network for global commercial use’, Cointelegraph, 27 April 2020 (https://cointelegraph.com/news/ china-launches-blockchain-based-service-network-for-global-commercial- use).

(44) Partz, H., ‘China’s blockchain project BSN to pilot global CBDC system in 2021’, Cointelegraph, 15 January 2021 (https://cointelegraph.com/news/china-s- blockchain-project-bsn-to-pilot-global-cbdc-system-in-2021).

(45) ‘Asian digital currency gets PBoC support’, China Daily, 25 February 2021 (http://www.china.org.cn/business/2021-02/25/content_77247856. htm?f=pad&a=true).

(46) Zhao, W. and Pan, D., ‘Inside China’s pan to power global blockchain adoption’, Coindesk, 14 April 2020 (https://www.coindesk.com/inside-chinas- plan-to-power-global-blockchain-adoption).

(47) Mohsin, S., ‘Biden team eyes potential threat from China’s digital yuan’, Bloomberg, 12 April 2021 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2021-04-11/biden-team-eyes-potential-threat-from-china-s-digital- yuan-plans).

(48) ‘China’s official digital currency ‘imminent’, People’s Daily, 10 December 2019 (http://en.people.cn/n3/2019/1210/c90000-9639253.html).

(49) Palmer, D., ‘BRICS nations ponder digital currency to ease trade, reduce USD reliance’, Coindesk, 16 November 2019 (https://www.coindesk.com/brics- nations-ponder-digital-currency-to-ease-trade-reduce-usd-reliance).

(50) Kumar, A. and Rosenbach, E., ‘Could China’s digital currency unseat the dollar?’, Foreign Affairs, 29 May 2020.

(51) ‘Chinese internet users turn to the blockchain’, op.cit.

(52) EU Blockchain Observatory and Forum, ‘About’ (https://www. eublockchainforum.eu/about).

(53) European Commission, ‘Digital technologies – Actions in response to coronavirus pandemic’, 26 February 2021 (https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single- market/en/content/digital-technologies-actions-response-coronavirus- pandemic).

(54) ‘Blockchain strategy’, op.cit.

(55) Reuters Graphic, ‘Blockchain bets in China and the West’, 20 October 2019 (https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/editorcharts/CHINA- BLOCKCHAIN/0H001QXFX95Q/index.html).

(56) European Central Bank, ‘A digital euro’ (https://www.ecb.europa.eu/paym/ digital_euro/html/index.en.html); Reuters, ‘Digital euro may still be five years away, ECB’s Panetta says’, 19 March 2021 (https://www.reuters.com/article/us- ecb-euro-digital-idUSKBN2BB15Z).