West Africa and the Sahel continue to be plagued by fragility, conflict and violence. Faced with challenges ranging from the spread of Boko Haram to persisting food insecurity, forced displacement, and youth unemployment, the region needs help. In response, the international community has marshalled significant resources to support governments in fostering the essential preconditions for peace – inclusive security and sustainable development. Such tasks can devour the funds of even the most ambitious aid programmes, while the reality of budgetary constraints calls for a constant search for efficiency.

The European Union’s engagement in Security Sector Reform (SSR) is a case in point. Transforming security and justice systems in fragile states is one of the top priorities of the EU’s external action. According to its 2016 SSR framework, the EU will help partner countries put the military under civilian oversight and provide effective, legitimate and accountable security and justice services to their citizens.1 EU programmes will apply a comprehensive approach aimed at: (i) formulating integrated security and justice policies and setting up national coordination mechanisms; (ii) providing training and non-lethal equipment to defence and security forces; and (iii) building internal accountability mechanisms and systems for human resources planning, budgeting, and financial management.2

In 2017, €2.5 billion in Official Development Assistance (ODA) managed by the European Commission was allocated to governance and civil society, including SSR.3 There are ongoing or planned rule-of-law, security and justice programmes in more than 40 countries worldwide.4 In West Africa, EU institutions have channeled over €100 million to finance the nascent 5,000-strong G5 Sahel Joint Force, while assistance for stabilisation in the region has reached €400 million.5

The EU has also launched three Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) missions. In Mali and Niger, capacity-building missions (EUCAP) provide technical assistance, training and equipment for internal security forces to fight against terrorism, organised crime and irregular migration. The EU Training Mission in Mali (EUTM) has been helping the government to restructure eight army battalions.6 France has deployed 4,000 soldiers for Operation Barkhane in Mali, Niger, and Chad, an endeavour that costs about €600 million per year.7 Meanwhile, development funding to improve security outcomes by tackling the root causes of conflict has also risen. The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa allocated almost €1 billion to Lake Chad and the Sahel, with projects in Mali, Niger, Nigeria and Senegal supporting youth employment, private sector development, social protection, health and education.8

Given the scale of the investment, the following questions arise: what is the value for money of each additional euro spent on strengthening West Africa’s armies and police? How can SSR assistance lead to effective and sustainable reforms, and ultimately contribute to reduce fragility, conflict and violence?

This Brief seeks to answer these questions by analysing the introduction and implementation of the security sector public expenditure review (PER), a public sector governance instrument that assesses the economy, effectiveness and efficiency of governments’ security and defence allocations, including SSR programmes. Developed by the World Bank in partnership with the United Nations, this data-driven assessment tool can facilitate a policy dialogue between civilian administrators, soldiers, and diplomats on the affordability of armies and police, and can therefore maximise the impact of security assistance programmes. Following an overview of security expenditures in West Africa, the Brief outlines the genesis of security sector PERs and highlights lessons learned from implementation in Liberia, Mali and Niger. The conclusion then offers recommendations on how PERs can be applied by the EU to ensure affordability and national ownership of defence and security assistance programmes.

The costs of West Africa’s security

Greater EU assistance comes at a time when West African security forces are getting a makeover. Historically, African militaries have been grossly underfunded, sometimes because political leaders sought to deliberately weaken them and create unaccountable loyal parallel structures. The result has been poorly equipped, ill-trained armies who cannot neutralise security threats and, in some cases, become drivers of conflict in and of themselves.9

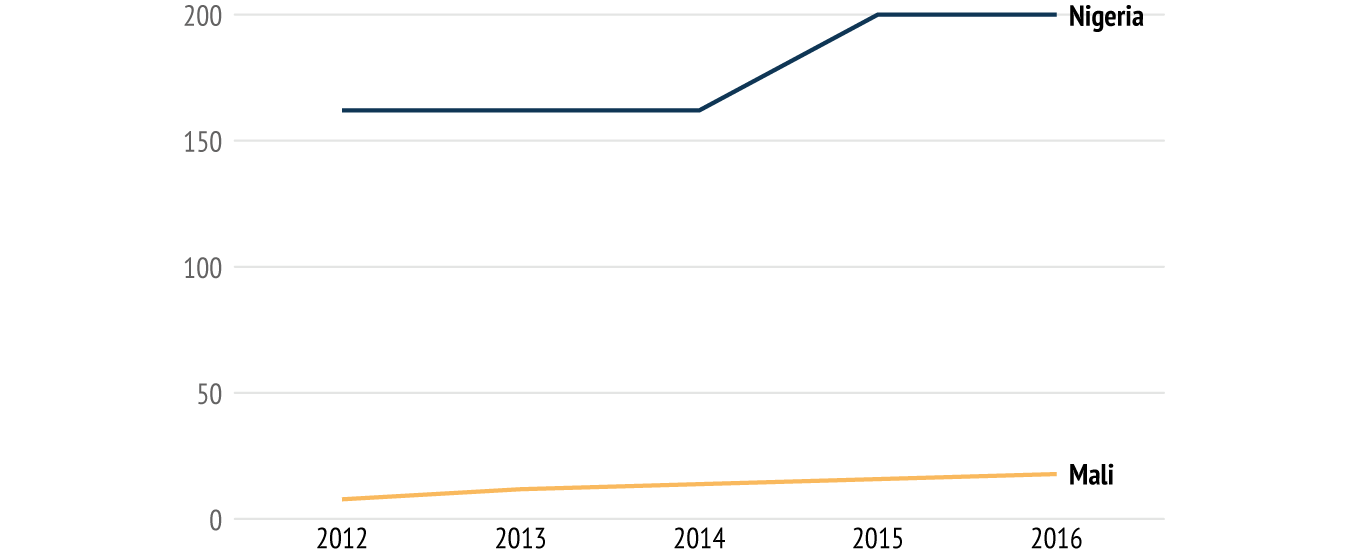

Figure 1: Increases in total military personnel (2012-2016)

Data: World Bank, 2019

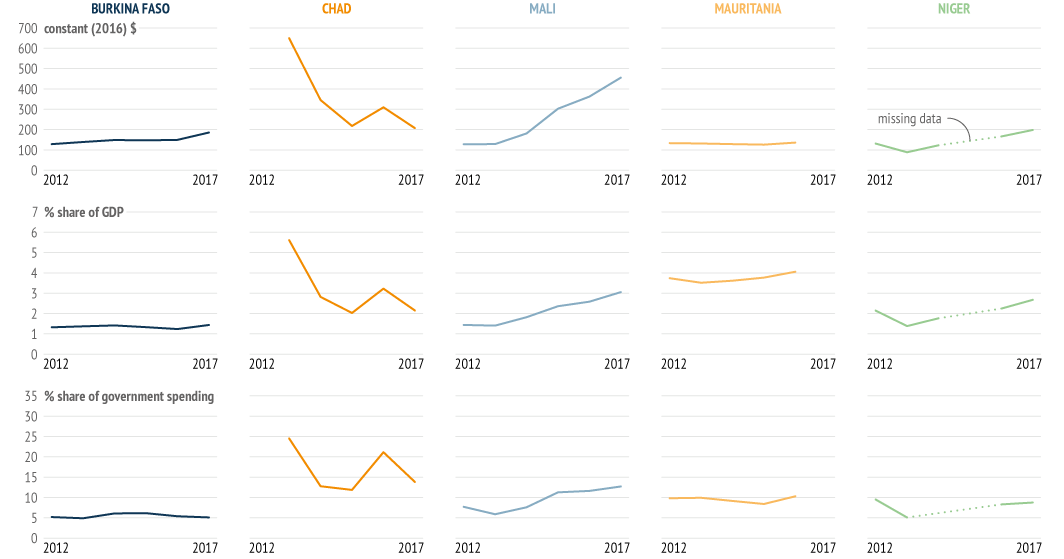

But amidst more intense regional cooperation, this trend has started to change. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), military expenditures in Africa rose by nearly 50% between 2007-2017, measured in constant 2016 US dollars.10 In the Sahel, Mali more than doubled the number of soldiers from 8,000 to 18,000 between 2012-2016, while the personnel of the Nigerian armed forces grew by 25% between 2014-2015 (see Figure 1). Spending on defence in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger more than doubled in the past five years. As a share of GDP, military expenditures have nearly tripled – with the notable exception of Chad – while most G5 Sahel countries allocate 10-15% of government spending to their armed forces (see Figure 2).11

Figure 2: Military expenditures in the Sahel

Data: Sipri, 2019

Security investments become even more significant when factoring in police and gendarmerie, whose numbers are difficult to compile due to cross-country variations in organisational models. For example, Nigeria’s defence spending – which far exceeds that of other countries in West Africa and topped $2 billion in 2018 – has been decreasing both in absolute terms, as well as as a share of GDP and government expenditures. This figure, however, does not cover the money allocated for police, whose standing force of 400,000 is double the size of the army. Even so, Nigeria’s army has deployed to all 36 states since 2015, a decision that both reflects and contributes to police malfunctioning. Indeed, the World Internal Security and Police Index (WISPI), which measures capacity, process, legitimacy and security outcomes, places Nigeria’s police at the bottom of the global list of 127 countries analysed in 2016.12

The value added of PERs in the security sector

More spending on defence and security is only the initial step in guaranteeing long-term peace and stability. For both international actors and national authorities, the greater challenge is to ensure that security expenditures are affordable, efficient, and effective. In other words, what is the value for money of each additional euro targeted at West Africa’s armies and police? How can donors and governments ensure that support is actually making a difference? Will African governments jeopardise their long-run economic prospects if they invest more in their security forces?

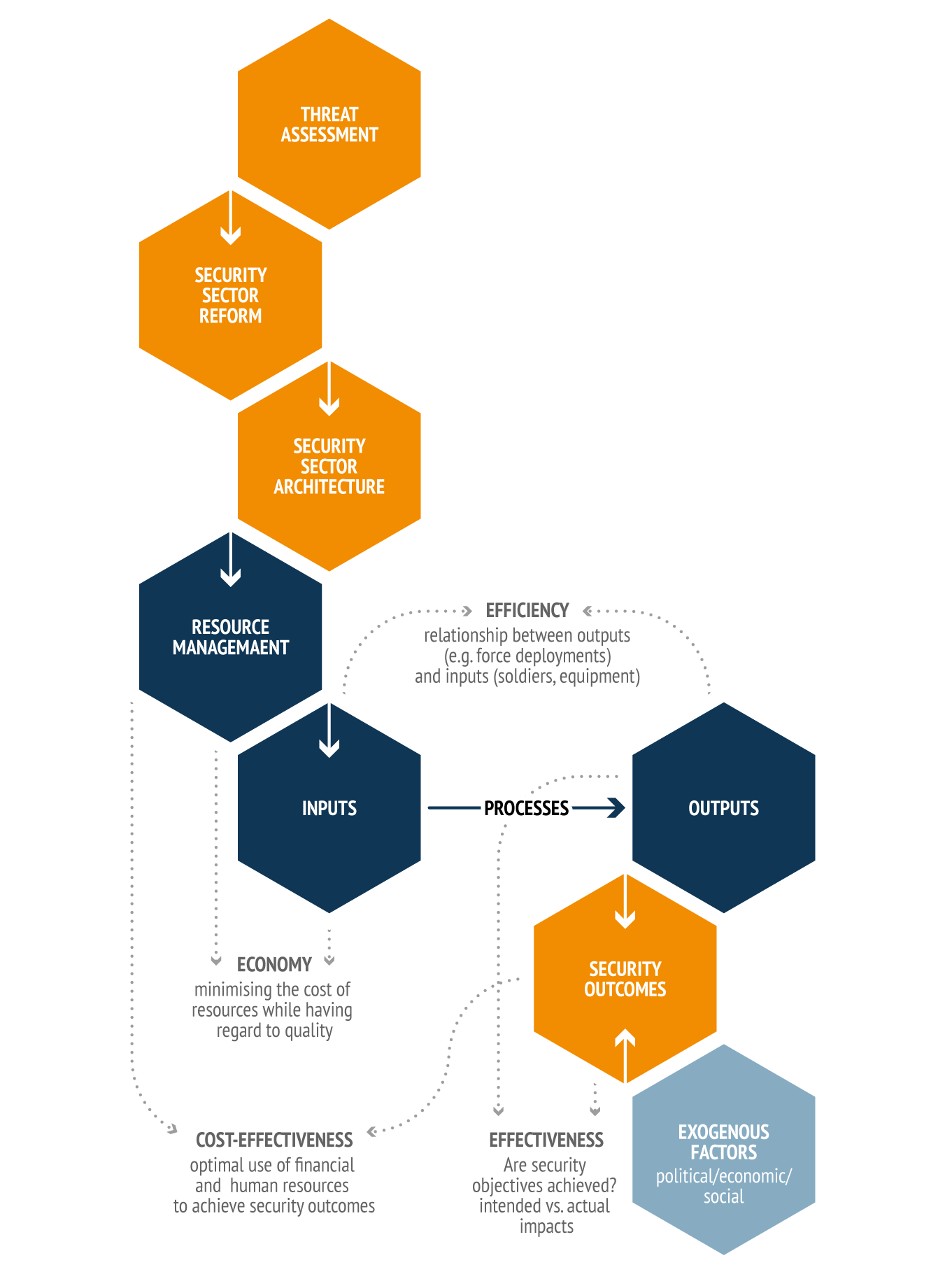

Answering such questions requires a data-driven policy instrument that links SSR priorities with economic and financial resource management. At the government's request, PERs examine government resource allocations within and among sectors, assessing the economy, efficiency and effectiveness of those allocations within a country’s macroeconomic context. In addition, a PER identifies the reforms needed in the budget cycle to improve the efficiency of public spending, assessing risks to public financial management (PFM) systems.13 Although PERs are the bread and butter of economists and public finance experts, the nexus with the security sector originates in the 2011 World Development Report (WDR) on Conflict, Security, and Development, which called for applying public sector governance tools to improve security and justice services in fragile states.14 The WDR 2011 underscored that the basic framework for expenditures should be the same for the military, police, and criminal justice system as for other sectors like health and education. Before spending money, governments should test the rationale for budget allocations and understand how these allocations affect the economy as a whole. They should also carefully study how paying more for military hardware and people (inputs) relates to actual combat or policing missions (outputs), and ultimately, to stability and public safety (outcomes).

Figure 3: Public Expenditure Reviews in the security sector – An overview

Data: World Bank, 2017

PERs of armies and police in fragile states thus provide a common platform for soldiers, diplomats and economists to tackle these questions together. As shown in Figure 3, they must first trace how security threats determine defence and public safety priorities, and investigate how the military, police, and possibly the gendarmerie are organised to achieve them. For example, if a country is confronted with high levels of organised crime, why is the army in charge of the government’s response and not the police? If there is a presidential guard, does it duplicate any of these roles and is it better financed? Once these answers are clear, the PER will then look into how money, people and assets are allocated and managed by these institutions. For instance, according to the Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability Framework (PEFA), policy-based budgeting is among the pillars of good public sector governance because it allows policymakers to direct resources on the basis of clear goals, and thus improve public service delivery.15 Are budget allocations for the military or police made on the basis of concrete strategies and policies? Do policymakers debate the rationale for additional spending, or are security institutions the privileged recipients of funds irrespective of budgetary constraints? With greater clarity on the macro picture, the PER will then delve into budget execution and oversight. For example, do the soldiers on the payroll actually exist? Are they paid on time? How is cash managed and are poor logistics affecting the speed and success of troop deployments in battle? Here some typical challenges include minimising the cost of resources, maximising the outputs (i.e., get more ‘bang for the buck’), and measuring progress on security outcomes. These criteria are known as the ‘three Es’ - economy, efficiency, and effectiveness.16

Lessons from PER implementation in Liberia, Mali and Niger

The security sector PERs undertaken by the World Bank at the specific request of the governments in Liberia, Mali and Niger between 2012-2014 hold valuable lessons for SSR programming. Lessons vary in their objectives, scope and depth. In Liberia (2012), the PER was a joint UN-World Bank exercise which examined the costs of transitioning away from a UN-led peacekeeping mission to the provision of security solely by national authorities. In Mali (2013), the PER identified risks and vulnerabilities in the public financial management of the army and police, while also running some long-term cost projections. In Niger (2014), the report forecasted rising defence expenditures in the wake of the Malian crisis. These analyses helped tackle sensitive policy issues with facts and data, breaking down the usual silos that emerge between soldiers scrambling to put together functional security institutions, and economists concerned with the long-term implications of additional security spending on development.

Knowing what to spend on

At the macro-level, the PERs in each country had to determine how security threats factor into spending priorities. In Liberia, the 2012 PER used policy objectives identified in the threat assessment prepared for the national security strategy together with the UN. The assessment concluded that stability was at risk of being undermined by disputes over land, high youth unemployment and the large numbers of demobilised soldiers and ex-combatants (about 117,000 in total). Liberia’s porous borders also made it vulnerable to political tensions and insecurity spilling over from Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea and Sierra Leone.17 In Mali, work on the PER started once the military junta that had staged a coup d’état in 2012 agreed to an ECOWAS-brokered transition. National security threats were far more urgent, with the army having to recover from desertions resulting from defeats to Tuareg rebels and regain lost territory in the north while negotiating the transfer of power back to civilians. In Niger, public safety was undermined by urban crime and disputes over land and livestock, while externally, the crises in Libya and Mali challenged the army’s ability to deter rebel attacks from abroad.

How did these trends shape strategic objectives? In Liberia, the potential for internal disorder to escalate into large-scale violent confrontations meant that the police became central to achieving stability. By contrast, the army was less important because external threats such as an invasion or proxy war were not foreseen as likely.18 The opposite was true in Niger. After the fall of the Libyan regime, the Nigerien army mounted the Malibéro operation, in which some 1,200 men were deployed to monitor the circulation of arms, fight terrorism, and deter an armed rebellion in the north.19 The short-run military response was complemented by the Security and Development Strategy in the Sahel-Sahara, which aimed to boost the capacity of the army and border police, as well as deliver services such as health, education and transport in sparsely populated areas vulnerable to security shocks.20 Meanwhile, the response to insecurity in Mali was primarily driven by the urgent need to recapture the north from rebel control and set up a UN-led peacekeeping mission.

Linking security threats to spending priorities is always easier on paper than in reality. Yet, an explicit policy consensus between security forces, civilians, international organisations and bilateral donors matters for several reasons. First, a systematic dialogue between defence and finance officials is missing even in developed countries, where the quality of public sector governance is higher, and civilian control over the armed forces is more entrenched. Such a dialogue is far more urgent in West Africa, where the pervasiveness of fragility and conflict require governments to make difficult short-run trade-offs between security and development expenditures. Second, disaggregating budget allocations between the military and police and comparing them against national security objectives can help decision-makers better understand how defence and security functions are funded. This is a first-order challenge in Africa, where threats to public order are often contained through internal military deployments, rather than effective policing. Third, identifying the right spending decisions can help donors and international organisations better direct their funding to alleviate the most pressing shortcomings affecting defence and police.

Knowing what is affordable

New security investments can weigh heavily on national budgets. In Mali, the 2012 coup and the territorial dispute in the north introduced new risks to medium-term macroeconomic stability. Previously, the country had grown at 5% between 2005-2010. Yet a drought in 2011 led to a decline in growth, and 1.5% contraction in real GDP. As a result, government revenues fell by 30%.21 This happened at a time when the post-coup transition and the rebellion in the north required the government to spend more on defence and security. Thus, while revenues fell, security sector budget allocations went up by 37%, while the proportional weight of security expenditures in the general budget doubled.

The Mali PER looked into whether this increase was fiscally sustainable. Under various scenarios constructed based on the country’s medium-term budget framework, the report concluded that defence and security spending could range anywhere between 9 and 25% of the budget in the near future. Three stabilising factors helped minimise this impact: (i) the resumption of the external budget support following the ECOWAS-brokered transition deal; (ii) the ability of the government to increase domestic revenue collection; and (iii) the deficit targets set by the government. As a result, defence and security spending was expected to account for around 12 % of the budget, and could be affordable if the government redirected money from other sectors.22

The impact of growing security costs on fiscal space was more clear-cut in Liberia. The PER estimated that the total cost of maintaining public order between 2012-2019 stood at $712 million. The bulk of this amount accounted for salaries, allowances and pensions paid to the Liberian forces, as well as non-wage recurrent costs such as equipment maintenance. However, given the revenues projected in Liberia’s medium-term expenditure framework (MTEF), the PER estimated that a financing gap of $86 million would emerge between 2012-2018. To address this shortfall, the study recommended that the ministry of finance join the national security council to explore ways to reallocate funds or identify cost-cutting measures together with officials in uniform.23

In Niger, the PER measured the impact of rising security expenditures on the overall fiscal deficit. Prior to the crisis in Libya and Mali, Niger’s MTEF forecast a downward trend in defence and security spending. This was difficult to justify given existing threats, as well as the urgent capital investments in the army. The PER determined that multiyear security sector budget estimates were neither realistic, nor achievable: ‘All things being equal, and without taking personnel expenditures into account, it would have taken over 30 years to respond to the needs that were deemed priority needs.’24 The PER put forth multiple scenarios based on pre-crisis security spending levels and revenues, but also examined the possibility that rising threats and renewed military engagements would become the ‘new normal’. In the most pessimistic projections, the investments wanted by the ministries of defence and internal security would have required additional revenues from taxation or more foreign aid.

Affordability analyses of defence and security reveal that fragile states in West Africa must make tough trade-offs when financing people in uniform. Investments in equipment or personnel necessary to enhance the state’s monopoly on the means of violence are unavoidable if countries want to control large portions of territory. Even when massive fiscal deficits can be averted, as in Mali, reallocations from other sectors or additional external assistance may be needed. Moreover, external security assistance can be the ‘make it or break it’ factor between financially realistic and untenable security investments. Yet none of the PERs examined this issue in depth. Off-budget funding for military and police thus remained off-limits.

Knowing how to care for assets and people

Analyses of macro-fiscal implications of security and defence spending can thus anchor SSR planning within realistic budget envelopes. But investigating budget execution brings to light financial management challenges that can undermine not only long-term affordability, but also the operational effectiveness of militaries and police.

In Niger, the lack of effective asset management was one of the main challenges to the PFM integrity of the armed forces. A strong asset management capacity has two advantages. First, it helps ensure that equipment is efficiently allocated to operative units. Second, it helps reduce transparency risks and prolongs the life of the equipment, which contributes to a better economic return on investments. New investments in security between 2010-2012 resulted in additional recurrent costs for supplies and people. But the security personnel in charge of equipment were insufficiently trained, and departments lacked consistent standard operating procedures. Internal control of asset management was largely on paper and regular power outages limited backup capacities.25

Mali faced similar challenges. In 2012, the armed forces acquired approximately 160 troop-carrying vehicles, five tank carriers, light and heavy weapons, as well as T-55 tanks. Money for maintenance and upkeep was scarce, and the majority of funds were centrally managed by a directorate which decided on a case-by-case basis whether to honour requests for repairs or parts that were too costly. This practice caused delays that were detrimental to actual military operations against rebels. This problem could have explained why the army kept an entirely separate special account for the ‘Northern Zone’. But this too was a major source of vulnerability in the PFM system because there was no real spending ceiling, the purpose and operating conditions of the special account were not adhered to, and budget charges lacked transparency.26

In Liberia, human resource management of internal security forces emerged as one of the central challenges in the transition to domestic security provision. The police had weak command and control functions. It numbered 4,200 people in 2012, but had to double its size to effectively take over public order management from the UN, a real challenge for the police academy. Moreover, the government had to establish a new pay and grading structure, as well as incentives for promotions.27

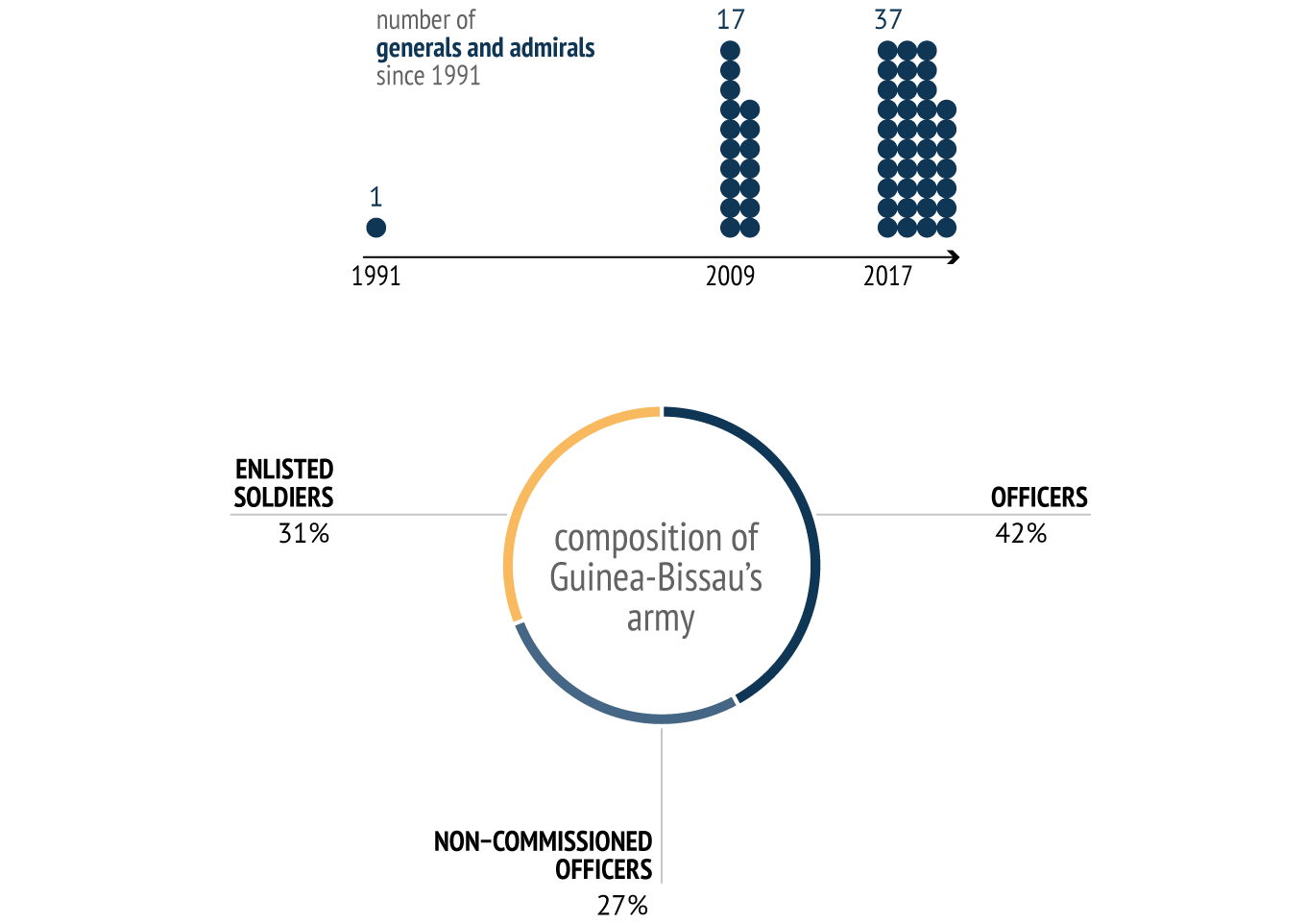

While these challenges are typical for police – where the payroll accounts for as much as 80% of costs – they are particularly relevant for African militaries too. In Niger and Mali, the governments had to spend a lot of money on new equipment. But in many other countries, effective SSR is complicated by weak personnel management, as top-heavy armies with imbalanced rank pyramids cannot execute operations effectively. An analysis conducted by the UN in Guinea-Bissau revealed that resource mismatches and political capture had weakened the military over the past three decades. For example, in the army there was a rise in promotions based on political patronage: in the 1990s, it only had one general, while in 2009 it had 17, and in 2016 there were 37. As such, 80% of soldiers were over the age of 40 in 2016, and with no retirement structure in place, most soldiers preferred to stay in the ranks. As shown in Figure 4, only 31% of the roughly 4,000 soldiers were enlisted troops.28

Figure 4: Army personnel structure in Guinea-Bissau

Data: ISS Aftrica, 2019

Implications for EU security assistance in West Africa

Since armies and police embody state power, looking into how much money people in uniform spend and how effectively they work is a high-risk project. Development banks and financial institutions can provide the technical know-how to assess defence and security expenditures with public finance tools. Data and sound technical analysis can help match SSR ambitions with the realities of budgetary constraints.

For these reasons, and looking at the lessons from West Africa’s case studies, the potential of security sector PERs to create value added in EU SSR programmes is significant. Since 2006, most of the 35 CSDP missions included programmes to reform police or improve the policy coordination between security and justice institutions. But an evaluation conducted in 2016 to help craft the EU’s new SSR framework argued for several improvements. These included grounding programmes in deeper local knowledge, synchronising technical support with diplomatic efforts to secure the buy-in of national authorities, and shifting away from project-based interventions to more sustainable budget support. What more could be done?29

First, the EU could require security sector PERs as preconditions for deploying new financing for SSR or security assistance more broadly. The European Development Fund (EDF) has disbursed €2.2 billion to the African Peace Facility since its creation to finance African-led peace operations, build the capacity of the African Union Commission, and provide funds for emergency response.30 The EDF could also be used as an instrument for SSR in Africa by financing large-scale budget support for defence and security forces. To this end, findings of security sector PERs could identify the conditionalities for the direct transfer of EDF money to national budgets.

Second, the EU could work with its partners to transform security sector PERs into standard instruments of international engagement, similar to Recovery and Peacebuilding Assessments (RPBAs). RPBAs are partnership frameworks which help donors, international institutions, and governments to align their programmes by identifying post-conflict recovery priorities together.31 Security sector PERs could fulfil the same role for external support to armies, police, and courts, whether on a national or regional basis. For example, out of 16 existing peacekeeping missions around the globe, only two have been costed – Liberia and Somalia. The EU could thus work with bilateral and multilateral partners to make security sector PERs mandatory for all such UN missions which feature a peacekeeping mandate.

For West Africa and the Sahel, the challenges posed by fragility, conflict and violence are real and urgent. Whether by way of moral obligation or geopolitical interest, more money and EU resources are now available to help countries in the region contain chaos and become more resilient. But only the best technocratic instruments can maximise the value of such investments, turning strategic visions into concrete results. Security sector PERs are one such instrument which the EU could deploy to become an even more effective security provider in West Africa.

References

* Paul M. Bisca is Security and Development Analyst residing in Washington, DC. He is co-author of Securing Development: Public Finance and the Security Sector, a joint United Nations-World Bank guidebook examining defense and police expenditures in conflict-countries. He also contributes to the Brookings Institution’s 'Future Development' blog, and is currently a consultant at the World Bank. The findings, interpretations, conclusions, and views expressed in this Brief belong solely to the author, and not necessarily to any institution the author is currently affiliated with.

1) European Commission, “Supporting Security Sector Reform – SSR,” https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/policies/fragility-and-crisis-management….

2) European Commission, “Elements of an EU-wide Strategic Framework to Support Security Sector Reform,” Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council, Strasbourg, July 5, 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/joint-communication-ss….

3) European Commission, 2018 Annual Report on the Implementation of the European Union’s Instruments for Financing External Actions in 2017, Luxembourg, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/annual-report-2018-hre….

4) European Commission, “Supporting Security Sector Reform – SSR”.

5) “The European Union’s Partnership with the G5 Sahel Countries,” EUCAP Sahel Mali, Factsheet, https://eeas.europa.eu/csdp-missions-operations/eucap-sahel-mali/46674/….

6) Ibid.

7) “France May Take the Lead in Fighting Jihadists,” The Economist, September 20, 2018, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2018/09/20/france-may-….

8) European Commission, 2017 Annual Report on the Implementation of the European Union’s Instruments for Financing External Actions in 2016, Luxembourg, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/annual-report-2017_en….

9) Valérie Arnould and Francesco Strazzari, “African Futures: Horizon 2025,” Report no. 37, European Union Institute for Security Studies, Paris, September 2017, https://www.iss.europa.eu/sites/default/files/EUISSFiles/Report_37_Afri…. Nan Tian, Pieter D. Wezeman, and Youngju Yun. "Military expenditure transparency in sub-Saharan Africa," SIPRI Policy Paper 48, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), November 2018, https://www.sipri.org/publications/2018/sipri-policy-papers/military-ex….

10) Ibid.

11) Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), “SIPRI Military Expenditure Database,” https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex.

12) International Police Science Association (IPSA), World Security and Police Index 2016, 2016, http://www.ipsa-police.org/Images/uploaded/Pdf%20file/WISPI%20Report.pdf.

13) Bernard Harborne, William Dorotinsky and Paul M. Bisca, eds., Securing Development: Public Finance and the Security Sector (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2017), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25138.

14) World Bank, World Development Report 2011: Conflict, Security, and Development (Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2011), https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/WDR2011_Full_Text….

15) PEFA: Improving Financial Management, Supporting Sustainable Development, “The PEFA Framework,” https://www.pefa.org/content/pefa-framework.

16) UK National Audit Office, “Assessing Value for Money,” https://www.nao.org.uk/successful-commissioning/general-principles/valu…. See also Stephen Aldridge, Angus Hawkins and Cody Xuereb, “Improving Public sector Efficiency to Deliver a Smarter State”, Civil Service Quarterly Blog, January 25, 2016, https://www.nao.org.uk/successful-commissioning/general-principles/valu… https://quarterly.blog.gov.uk/2016/01/25/improving-public-sector-effici….

17) United Nations and World Bank, Liberia Public Expenditure Review Note: Meeting the Challenges of the UNMIL Transition (Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2011), http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/524941468055756666/pdf/710090….

18) Ibid.

19) International Crisis Group, “Niger: Another Weak Link in the Sahel?”, Africa Report no. 208 , Brussels, 2013, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/west-africa/niger/niger-another-weak….

20) International Peace Institute, “Republic of Niger Strategy for Development and Security in Sahel-Saharan Areas of the Country,” https://www.ipinst.org/2013/04/republic-of-niger-strategy-for-developme….

21) Paul M. Bisca and Gary J. Milante, “Insights from the Development Sector” in Effective, Legitimate, Secure: Insights for Defense Institution Building, ed. Alexandra Kerr and Michael Miklaucic (Washington D.C.: National Defense University, 2017), https://cco.ndu.edu/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=1WN7fgrBpq4%3d&portalid=96.

22) Harborne et al, Securing Development.

23) United Nations and World Bank, Liberia Public Expenditure Review Note.

24) Harborne et al, Securing Development.

25) Ibid.

26) Ibid.

27) United Nations and World Bank, Liberia Public Expenditure Review Note.

28) UNIOGBIS and Institute for Security Studies, “Relaunching Defence and Security Sector Reforms in Guinea-Bissau,” Policy Brief no. 5, May 2018, https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/policybrief-guineabissa…;

29) European Commission, “Lessons Drawn from Past Interventions and Stakeholders’ Views. Accompanying the document Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council Elements for an EU-wide strategic framework to support security sector reform,” July 5, 2016, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX%3A52016SC….

30) European Commission, African Peace Facility: Annual Report, Luxembourg, 2018, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/apf-ar-2017-180711_en….

31) World Bank, “Recovery and Peacebuilding Assessments,” http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/brief/recov… -and-peace-building-assessments.