Long gone are the days when Eastern Europe was Russia’s exclusive backyard. The last decade has witnessed the rapid expansion of political and economic ties between powers from the Middle East and Asia and East European states. While much of the analysis on the rise of these powers is usually focused on China and its One Belt One Road march across the post-Soviet world, the role of other Asian powers remains underexplored. Whereas China’s penetration of the region has been in the spotlight, Japan’s charm offensive to rekindle diplomatic, political and economic ties with Eastern Europe has tended to be overlooked. In the last five years, Japan has opened three new embassies in the region (in Armenia, Belarus and Moldova), Japan’s prime minster has paid the first official visit to Ukraine in the history of bilateral relations between the two countries and the Japanese foreign minister travelled to all three South Caucasus republics. More recently, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic Japan pledged to provide the flu drug Avigan to Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine free of charge. All this raises the question why, despite such a great geographical distance, Eastern Europe matters to Japan?

The aim of this Brief is threefold. Firstly, to outline the place of Eastern Europe in Japan’s foreign policy and shed light on the drivers shaping Tokyo’s approach. Secondly, to assess Japan’s economic presence as well as the amount of development aid it has provided to East European states. Thirdly, to reveal similarities between Japan’s and the EU’s strategies in this region and ultimately, to identify areas of cooperative synergy.

The third pillar

For a long time, Japanese foreign policy was based on two pillars: (i) the alliance with the US, the cornerstone of Japan’s security; and (ii) strengthening economic and political relations with immediate powerful neighbours, such as China, South Korea and Russia. But in 2006 Japan formalised a third pillar.

Taro Aso, the then Japanese minister for foreign affairs, unveiled the concept of the ‘Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’,1 which articulated Japan’s approach towards the states of Eurasia (apart from China or Russia), including six Eastern European states – Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. On a strategic level, the new pillar aimed to enhance Japan’s contribution to its security alliance with the US. This was essentially a burden-sharing exercise, whereby Tokyo sought to uphold the US agenda in other regions of the world. The initiative coincided with Japan’s changing self-perception and transformation into a more self-confident power – reflected in Japan’s deployments of its Self-Defence Forces (SDF) to the Indian Ocean and Iraq, as well as in a generally more proactive foreign and security policy. Last but not least, the third pillar encroached on what Russia regards as its ‘near abroad’. By pivoting to Eastern Europe, Tokyo sought to catch Russia’s eye and make it take Japan more seriously. 2

By pivoting to Eastern Europe, Tokyo sought to catch Russia’s eye and make it take Japan more seriously.

On an operational level, Japan sought to support economic and democratic reforms in certain countries of the Eurasian continent under the banner of the ‘Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’, based on such shared universal values as freedom, the rule of law and the market economy. Tokyo anticipated such a process in the region to be a long-term endeavour. In this scenario, Japan cast itself in the role of a patient ‘escort runner’ accompanying countries undertaking economic reforms and development.3

The formalisation of the third pillar did not mean that Japan had traditionally been absent from the region. Since the 1990s Japan has been providing technical assistance and financial aid across this large geographical area. The key aim of the new third pillar was to strengthen and consolidate Japan’s economic and political engagement in the region, while Japan’s effort at branding its Eurasian policy sought to give legitimacy to its presence in this part of the world.

Furthermore, formalisation of the third pillar aimed to highlight Japan’s regional priorities within Eurasia. More precisely, the concept unveiled how Japan intends to relate to various regional groupings that have emerged since the collapse of the Soviet Union. With regard to Eastern Europe, Japan invoked as its potential institutional interlocutor the grouping of states composed of Georgia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan and Moldova (GUAM),4 established in 1997 and formalised as the GUAM Organisation for Democracy and Economic Development in 2001. The choice was motivated by the grouping’s declarative adherence to universal values, reformist aspirations and Western-leaning orientation.5 In other words, normative compatibility has played a role in determining Japan’s engagements in Eastern Europe.

In 2007, a year after the third pillar was presented, but two years before the launch of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) by the EU, Japan established the ‘GUAM + Japan’ format6 as a framework for high-level dialogue and mutual cooperation. The ‘Central Asia+Japan’ Dialogue, launched in 2004 as the institutional channel for dialogue and cooperation between Japan and the five Central Asian republics, served as the blueprint for this format. This indicates that, as a rule, when Tokyo seeks to deepen relations in Eurasia it prefers to engage with a set of states grouped around a sub-regional organisation.

Three security drivers

Geographical distance does not mean that Japan’s security is unconnected with developments in Eastern Europe. If anything, the war between Russia and Ukraine since 2014 has validated Japan’s foreign policy course in the region and underscored the need to pre-empt possible negative impacts on Japan’s national interests. Three issues stand out for Japan: the forcible change of Ukraine’s borders by Russia; the transfer of military technologies and equipment from Eastern Europe to China; and the weakening of the non-proliferation regime.

A dangerous precedent

Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the subsequent war in Eastern Ukraine run counter to the fundamental principles of Japanese foreign policy. In a policy speech immediately following his inauguration in 2013, Japan’s prime minister Shinzo Abe stressed that ‘developing a strategic diplomacy based on the fundamental values of freedom, democracy, basic human rights, and the rule of law will be fundamental to our diplomacy.’7 At that time China’s assertive actions at sea, especially around the Senkaku islands which have been disputed by Tokyo and Beijing since the 1970s, posed one of the most serious security challenges to Japan – and this is still the case today. To counter Chinese attempts to restrict air traffic over the islands Japan sought international support for its pursuit of an ‘open and stable seas’ policy.8 Only a year later the dramatic events in Ukraine set a dangerous precedent that could potentially be replicated in the Far East, prompting Tokyo to react.

Tokyo underlined that Japan does not accept ‘changes to the status quo by force or coercion’, insofar as such violations of territorial integrity may also have global repercussions that could jeopardise Japan’s security.9 This indicated that Japan is concerned that China might emulate Russia’s example in its own neighbourhood. Tokyo used diplomatic leverage to ensure that these actions met with wide international condemnation, and sponsored a resolution on the ‘Territorial integrity of Ukraine’, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations (UNGA) on 27 March 2014.10 In the wake of the 2018 incident in the Kerch Strait which prevented free passage of Ukrainian military ships and resulted in the disruption of commercial traffic from the Black Sea to the Azov Sea, Japan threw its weight behind another UNGA resolution condemning Russia’s illegal behaviour11 This stance is unlikely to change.

Military transfers to China

The second issue that is of concern to the Japanese relates to transfers of military technology and equipment from Eastern Europe to China, which risk upsetting the power balance in Asia and precipitating a military clash. Ukraine, with its vast military-industrial complex developed during Soviet times, poses a particular challenge in this regard. Back in 1998 a private company in Macau procured the unfinished Soviet aircraft carrier Varyag from Ukraine on the pretext that it would be refurbished as a floating casino.12 However, more than ten years later, after extensive refitting and modernisation, Varyag re-emerged as Liaoning, China’s first operational aircraft carrier.

As Ukraine moved in 2014 to cease cooperation with Russia in the military-industrial sector, the risks of such transfers increased. Without Russia as a traditional customer, some cash-strapped Ukrainian defence companies were looking for alternative solutions, including in China. And Beijing was happy to step in and take advantage of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Beijing Skyrizon Aviation, a partially state-owned Chinese corporation, attempted to purchase a controlling stake in Ukraine’s top aerospace manufacturer Motor Sich. The plans foresaw jointly building a factory in China and bringing in Ukrainian engineers.13 One Chinese media outlet described Motor Sich as ‘a pearl of Ukraine’s aircraft engine building’ which China managed to ‘snap up from the US and Russia’.14 In fact, the deal has been suspended, as the Ukrainian authorities are struggling to strike a balance between the need to keep the company afloat and concerns raised by the US. It remains quite important in the mid- and long-term perspective for Japan to prevent any leakage of military or other crucial technologies to China from economically vulnerable Ukraine and other EaP countries (e.g. Belarus), which could have an adverse impact on the security situation in and around Japan.

Challenge for non-proliferation

Tokyo’s third concern is North Korea’s nuclear programme which undermines the non-proliferation regime and directly imperils the national security of Japan. On the one hand, it is critically important for Tokyo to continue winning political and diplomatic support in international fora worldwide, Eastern Europe included, in its efforts to raise the costs for North Korea.15 In this regard, the war in Ukraine raises a serious question about how to convince North Korea to agree to eliminate its nuclear arsenal, given that Russia reneged on its commitment in the Budapest Memorandum to guarantee Ukraine’s security and territorial integrity in exchange for Kyiv giving up its nuclear weapons. There is in fact little incentive for North Korea to accept denuclearisation in the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea. The lesson probably drawn in Pyongyang is that nuclear weapons are the ultimate guarantee against attempts by rivals to orchestrate a regime change. This puts Japan in a difficult diplomatic position.

The Russian factor

Although Japan joined the chorus of international condemnation following the annexation of Crimea, the Russian factor imposes certain constraints on Tokyo. Since the end of World War II, one of the most challenging diplomatic tasks for Japan has been resolving a territorial dispute with Russia around the so-called Northern Territories – a handful of islands off the coast of Hokkaido that, according to Tokyo, ‘the Soviet Union unilaterally incorporated under occupation into its own territories without any legal grounds.’16 A day before taking up office, prime minister-elect Shinzo Abe declared his ambition to ‘resolve [this] territorial dispute and sign a peace treaty’ with Russia.17 Since then, the Japanese leader has strived to build a good personal relationship with his Russian counterpart, in his view one of the key preconditions for a possible future agreement. This led Prime Minister Abe to attend the Sochi Olympic Games opening ceremony in 2014, which raised questions about the consistency of Japan’s value-driven foreign policy, as many Western leaders refused to attend the event due to growing human rights abuses in Russia.

The dilemma has further deepened since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the armed conflict in Eastern Ukraine. On the one hand, this was a clear case of change of status quo by force, which Japan has condemned. On the other hand, Shinzo Abe remained committed to his goal of engaging the Russian leadership to push negotiations on the disputed islands forward. As Russia moved even closer to China after 2014, Japan also sought, if not to obstruct, then to actively discourage this Sino-Russian rapprochement.

Tokyo’s ambivalence was clearly reflected in the sanctions Japan imposed on Russia. In comparison with those applied by the US and the EU, they were introduced two months later and were much softer and more limited in scope. For example, Japan’s sanctions did not target the Russian energy sector, which is vital for Russia’s economic stability. In addition, after a brief hiatus, Shinzo Abe re-engaged directly with Vladimir Putin in talks on the islands issue. In this way, Japan could tactically send a signal to Russia that Japan wished to maintain dialogue, while at the same time mount diplomatic pressure on Russia in concert with the US and the EU against changing territorial borders by force.

However, this complex balancing game did not pay off. Russia did not alter its approach towards China, while talks on the territorial dispute made poor progress. On the contrary, Russia kept expanding military infrastructure in the Northern Territories18 and argued that sanctions introduced by Japan obstructed the deepening of economic relations which, in the Kremlin’s view, is a precondition for any progress on the islands dispute.19

Room for growth in trade and investment

Japan’s policy in Eastern Europe is not only about security and support for reforms. It also includes an economic component, albeit one that is still underdeveloped. Trade and investments in the region are not massive, but if certain conditions are met there is room for growth in the next decade.

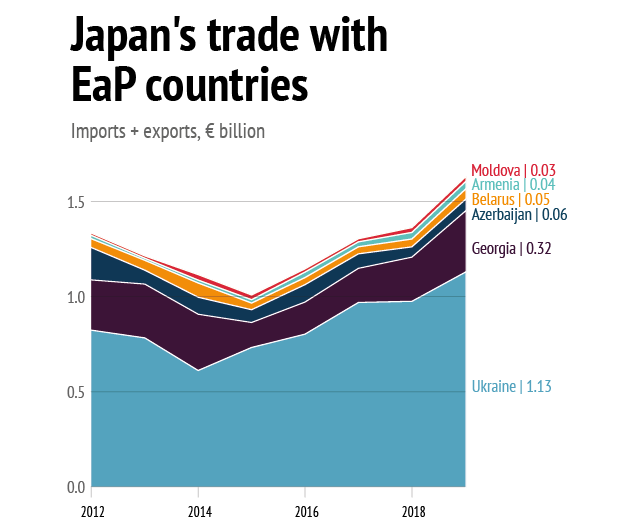

The statistics on trade between Japan and the six EaP countries during 2013-2019 reveal two features. Firstly, in terms of trade items, in general automobiles and machines are exported from Japan and raw materials such as aluminum and iron ore, as well as agro-products, are imported from the EaP states. Secondly, the trade volume between Japan and the EaP countries except for Ukraine is so small (compared to Japan’s other trade partners) that significant fluctuations may be observed year by year. For example, Japanese trade with Azerbaijan in 2018 decreased by 29.2% in 2018 but grew by 12.9% in 2019 year-by-year, while trade with Moldova grew by 54.9% in 2018 and only by 0.8% in 2019.

Data: CEIC, 2020

Japanese trade relations with Eastern Europe need a boost. However, there is no silver bullet to rapidly increase trade. One of the key measures in this regard could be free trade agreements (FTAs) and other economic accords which eliminate trade barriers and deepen trade liberalisation. For example, the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA), which entered into force in February 2019, contributed to the growth of EU exports to Japan by 6.6% and Japanese exports to the EU by 6.3% in the first ten months following its implementation.20 However, in principle Japan negotiates and signs FTAs only with countries with which it already has large trade volumes. To date, Japan has signed 18 free trade agreements and economic partnership agreements with partners in 21 countries and regions. The ratio of trade volume with these countries to Japan’s total amount of trade volume is 51.6%. This number further rises to 86.2% when trade with partners with whom Japan is currently negotiating an FTA is taken into account.21 Statistics for 2018 show that Japan’s trade volume with EaP states accounts for 0.11% of the total, so it is unlikely that Tokyo will in the short to medium-term engage in time-consuming negotiations to sign FTAs with EaP countries.

What can increase trade exchanges in the immediate future are the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) agreements signed between the EU and Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Although still limited, the positive effects of DCFTA agreements are beginning to be felt in Japan. This is due to improvements in product quality after the gradual introduction of European standards and legislative harmonisation with the EU.

Although still limited, the positive effects of DCFTA agreements are beginning to be felt in Japan.

Other associated EaP members Georgia and Moldova could adopt this model of increased exports to Japan. For example, it would be beneficial for them to increase trade volumes with Japan by exporting wine, an item which has been targeted by Russian embargoes in the past. This seems feasible, especially given figures which show Japanese consumers buy more and more wine every year. According to Mercian Corporation, from 1989 to 2019, consumption of wine in Japan has nearly quadrupled.22 Since both Georgian and Moldovan wines, which are already gaining popularity in Japan, have relative price competitiveness, they may boost exports to the Japanese market. These growing imports from the EaP countries also contribute to bolstering Japan’s food security and trade diversification, thus there is a clear benefit for Japan in supporting the Association Agreements, of which the DCFTA is an integral part.

Although still limited, the positive effects of DCFTA agreements are beginning to be felt in Japan.

Japanese direct investment in the EaP countries remains limited. According to the Japan External Trade Organization, as of August 2019 there were 38 Japanese companies in Ukraine, 11 in Azerbaijan and Belarus respectively, 6 in Georgia, 5 in Armenia and 4 in Moldova. The stock value of Japanese direct investment in Ukraine, which hosts the highest number of Japanese companies, is merely $139.2 million (2019).23 This value is less than one-tenth of Japanese direct investment in Russia ($1.92 billion),24 although this is quite natural as Russia is much closer geographically and has a much bigger market. In order to promote and increase Japanese investments in the EaP countries, concluding bilateral investment treaties would be desirable, if not necessary. Currently, Japan has such treaties with Ukraine (in force since November 2015) and Armenia (in force since May 2019), while negotiations continue with Azerbaijan and Georgia; however, there are no talks in this direction with Belarus and Moldova.

However, here again the DCFTA plays a positive role for Japanese companies. Some Japanese companies have recently started availing of DCFTA agreements between the EU and some EaP countries - for example, Japanese automotive components producers who export wiring harness from Ukraine and Moldova to the EU. More Japanese manufacturing and trading companies could expand their businesses to EaP countries, not only thanks to the cheap and skilled labour force available, but also given the advantages and benefits of DCFTA agreements with the EU.25 Such investments would be advantageous to all three parties – Japan, the EaP countries and the EU. In addition, it is worth mentioning that designer brand clothes, such as Prada, Moncler and Armani, have recently appeared as a new export item from Moldova, Georgia and Armenia to Japan. While still insignificant, these exports may indicate an upcoming trend, as a result of the DCFTA agreement which facilitated European companies moving their production capacities to the region.

Another important factor for Japanese companies is market size. Ukraine attracts Japanese investment primarily due to its potential – it is the largest economy and market among the EaP countries, and with long-standing economic ties to Japan. In fact, with 16 Japanese companies, Ukraine concentrates almost all Japanese business in the EaP region. Nevertheless, improving the investment climate through the support of values such as democracy and rule of law in the region is imperative, as Japanese business people cite corruption and the lack of rule of law as disincentives for investment.26

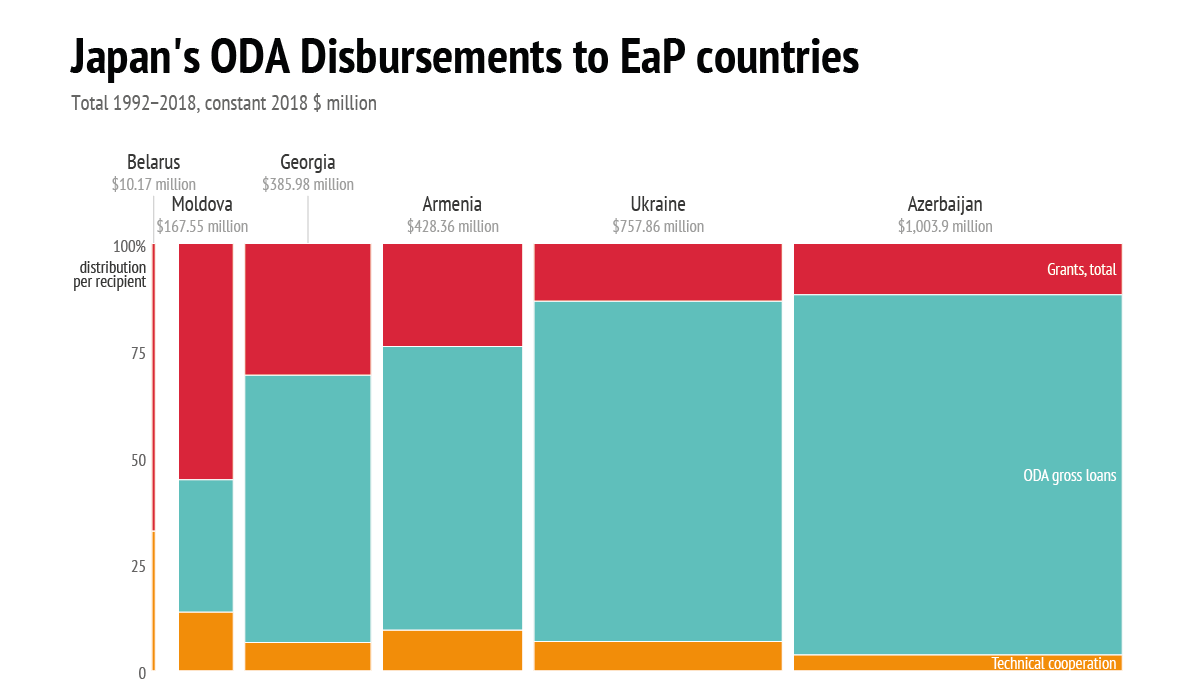

Conditional development aid

Although Japan’s budget for Official Development Assistance (ODA) is on a declining trend,27 Japan still remains one of the leading donors in Eastern Europe. According to the latest Japanese Development Cooperation Charter, Japan in Eastern Europe ‘will support the moves toward the integration of Europe, which shares universal values such as freedom, democracy, respect for basic human rights and the rule of law, by providing assistance necessary to this end.’28 However, it is a challenge for Japan to achieve these policy tasks while reducing the ODA budget. As for other big development donors, the dilemma for Japan is how to achieve ‘more with less’.

Nevertheless, despite budgetary constraints there are successful examples of development assistance in Eastern Europe. In Moldova, the Japanese government provides loans to local farmers enabling them to obtain agricultural equipment on preferential terms (e.g., payment in instalments, zero interest, etc.)29 Moreover, Japan in the years 2010-16 was the second-biggest donor (accounting for 15% of all aid) after the EU in Moldova’s autonomous Gagauzia region.30

Although Japan had already been offering assistance to victims of the Chernobyl disaster in Belarus and Ukraine, cooperation was stepped up after the incident at the nuclear energy plant in Fukushima in 2012. Since Belarus and Ukraine were able to share their knowledge and experience of the nuclear disaster with Japan, this cooperation has delivered benefits to both sides. Also, all EaP countries collected donations after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011. This demonstration of solidarity with Japan showed that Japanese assistance is not a ‘one way street’ and led to Japan having a rethink about planned cuts in its ODA budget.31

As the regional priority of assistance policy clearly shows, Japan supports democratic reforms and the European integration of the EaP countries. For example, Japan regularly sends electoral observers to the EaP countries and assists in the holding of fair and free elections. Japan is the number one Asian partner of the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) for cooperation and an important donor to the organisation’s Partnership Fund.32

Data: OECD, 2020

In the case of Japanese assistance to Ukraine, notwithstanding the ongoing armed conflict in Donbas33 conditionality is clear and Japan holds to a strict position, whereby ‘Japan is ready to continue its support towards Ukraine as long as Ukrainians pursue the path of reform.’34 Tokyo does not set out any clear and concrete conditions as the IMF or the EU do in their memoranda with the Ukrainian government, but in case of backsliding on reforms, potentially Japan could suspend its macroeconomic assistance, while continuing its humanitarian support to ordinary vulnerable citizens. This use of conditionality to induce reform efforts stands in stark contrast with the stance of other emerging donors, including China, and is in line with the EU approach of ‘more for more and less for less’ in Eastern Europe.

Although Japan initially viewed China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) negatively, Tokyo is not opposed to infrastructure investment and now considers it wiser to engage China in the hope of inducing it to change some of its bad practices rather than to ignore the BRI and watch how the initiative is implemented in more and more countries. Theoretically, it would be possible for Japan and China to cooperate in Eastern Europe to their mutual benefit. For example, cooperation is feasible in the logistics sector in Belarus, which is attracting increasing Chinese investment. However, such cooperation in the region would be possible only after the successful implementation of projects in a region of considerable strategic significance for both parties - South East Asia.

Strengthening synergies

Japan and the EU are like-minded powers which at the global level favour multilateralism and the primacy of international law. Unsurprisingly, Japan’s foreign policy goals in the eastern neighbourhood overlap with those of the EU. This is why Japan ‘underscores its support for the Eastern Partnership, which contributes to the democratization and promotion of market economy in Eastern Europe.’35 As Japan also benefits from the DCFTAs between the EU and the three EaP countries, it is in Japan’s interest to assist efforts to transpose EU norms and standards in EaP associated members.36

Japan closely follows the ongoing discussion in the EU on the way forward vis-à-vis Eastern Europe beyond 2020. Tokyo is considering a review of its policy as the region becomes more diversified in terms of external powers’ presence, and thus requires a more complex and thought-through approach. In fact, the region for now has no clear perspective of joining the EU, while Russia is actively working to bring it back into its own sphere of influence, and China is silently building its own geo-economic project there. An Eastern Europe squeezed between Russia and China is the least desirable scenario for Japan.

An Eastern Europe squeezed between Russia and China is the least desirable scenario for Japan.

All of this makes coordination between Japan and the EU in Eastern Europe more urgent and vital in the coming decade. However, there is currently no ongoing dialogue between Japan and the EU on coordinating assistance or policies in general to the EaP states. If both parties find it necessary to talk about the EaP, there are many possible dialogue formats. One is provided by the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement: it envisions that the Joint Committee in which both parties participate can be used to exchange views on issues of common interest (article 42). In addition, the EU could invite Japan to the EaP Summits as an observer, if such a need were to arise.

In which area does such cooperation look most promising? One sector with potential for successful cooperation is infrastructure.37 The question for Japan and the EU is how highly the EaP region is prioritised in each side’s respective investment policy, and to what extent they would consider investing in various projects in the region. Although the EU, together with the six EaP countries and financial institutions, has already worked out the so-called Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) Investment Action Plan,38 it would be better to coordinate investment projects with Japan in the framework of Japan-EU cooperation in connectivity.

A second area of possible cooperation between the EU, Japan and the EaP countries could be tourism, which – once the Covid-19 pandemic has been successfully addressed – has great potential for boosting economic growth and job creation through spillover effects on other sectors. The EaP countries that have established visa-free regimes with the EU could benefit more from greater people-to-people mobility, further deepen cooperation in the tourism sector and contribute to enhanced interconnectivity. Japan already has experience in cooperating with Central Asian countries in the tourism sector and could thus contribute to designing national strategies for developing the sector.

Japan and the EU are natural partners in Eastern Europe. However, the potential for building synergies between each other’s policies has not been fully explored and exploited. As both actors are set to re-assess their approach to the region in the light of dramatic geopolitical shifts, it is high time for both to engage in more strategic discussions on how best to promote overlapping interests in Eastern Europe.

References

* The views expressed in this publication are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of any institution with which he is currently affiliated.

** The author would like to thank Karol Luczka for his research assistance in writing this Brief.

*** In this Brief the term ‘Eastern Europe’ is used to denote the post-Soviet states of Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine, as well as the South Caucasus countries Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia.

1 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Diplomatic Bluebook 2007, https://www.mofa.go.jp/policy/other/bluebook/2007/html.

2 Tomohiko Taniguchi, “Beyond ‘The Arc of Freedom and Prosperity’: Debating Universal Values in Japan’s Grand Strategy”, Asia Papers Series 2010, The German Marshall Fund of the United States, October 26, 2010, http://www.gmfus.org/file/2298/download.

3 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Speech by Mr. Taro Aso, Minister for Foreign Affairs on the Occasion of the Japan Institute of International Affairs Seminar ‘Arc of Freedom and Prosperity: Japan’s Expanding Diplomatic Horizons’”, November 30, 2006, https://www.mofa.go.jp/announce/fm/aso/speech0611.html.

4 Diplomatic Bluebook 2007, op. cit.

5 Organisation for Democracy and Economic Development – GUAM, “Charter of Organization for democracy and economic development – GUAM”, May 23, 2006, https://guam-organization.org/en/charter-of-organization-for-democracy-….

6 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Joint Statement ‘Central Asia + Japan’ Dialogue/Foreign Ministers’ Meeting”, August 28, 2004, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/dialogue/joint0408.pdf.

7 Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, “Policy Speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the 183rd Session of the Diet”, January 28, 2013, http://japan.kantei.go.jp/96_abe/statement/201301/28syosin_e.html.

8 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “The 13th IISS Asian Security Summit -The Shangri-La Dialogue-Keynote Address by Shinzo ABE, Prime Minister, Japan”, May 30, 2014, https://www.mofa.go.jp/fp/nsp/page4e_000086.html.

9 Prime Minister of Japan and His Cabinet, “Japan and NATO As Natural Partners’ - Speech by Prime Minister Abe”, May 6, 2014, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/96_abe/statement/201405/nato.html.

10 “Toichi Sakata : Anneksiya Kryma – eto problema ne tol’ko Ukrainy, no i problema vsego mira” [Toichi Sakata: the annexation of Crimea is not only the problem of Ukraine, it is the problem of the world”], day.kyiv.ua, April 4, 2014, https://day.kyiv.ua/ru/article/den-planety/toichi-sakata-anneksiya-krym….

11 United Nations, “Problem of the militarization of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, Ukraine, as well as parts of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov : resolution adopted by the General Assembly”, December 17, 2018, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1656124?ln=en.

12 “Remember the Varyag”, The Wall Street Journal, December 3, 1998, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB912638337213805500.

13 Anton Troianovsky, “At a Ukrainian aircraft engine factory, China’s military finds a cash-hungry partner”, The Washington Post, May 20, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/europe/at-a-ukrainian-aircraft-eng….

14 "China on purchase of Ukraine’s Motor Sich defense plant: We’ve snatched ‘pearl of engine building’ away from US and Russia", UAWIRE, December 18, 2019, https://uawire.org/china-on-purchase-of-ukraine-s-motor-sich-defense-pl….

15 Organisation for Democracy and Economic Development – GUAM, “Joint Press Release of 5th GUAM-Japan Ministerial Meeting”, September 20, 2017, https://guam-organization.org/en/joint-press-release-of-5th-guam-japan-…; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Japan-Armenia Foreign Ministers’ Meeting”, September 3, 2018, https://www.mofa.go.jp/erp/ca_c/am/page6e_000137.html.

16 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Basic Understanding of the Northern Territories Issue”, March 1, 2011, https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/europe/russia/territory/overview.html.

17 Liberal Democratic Party of Japan, “Press conference of Shinzo Abe”, February 26, 2012, https://www.jimin.jp/news/press/president/128912.html.

18 “Also, Russia is proceeding with the development of military facilities in the Northern Territories. In November 2016, Russia announced that it deployed coastal (surface-to-ship) missiles to Etorofu and Kunashiri Islands”: Ministry of Defence of Japan, Defense of Japan 2019 (Annual White Paper), September 11, 2019, p.126, https://www.mod.go.jp/e/publ/w_paper/pdf/2019/DOJ2019_1-2-4.pdf.

19 The Kremlin, “Interview by Vladimir Putin to Nippon TV and Yomiuri newspaper”, December 13, 2016, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/53455.

20 European Commission, “First year of EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement shows growth in EU exports”, January 31, 2020, https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/press/index.cfm?id=2107.

21 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Initiatives in Japan’s Economic Partnership Agreements (EPA/FTA)”, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000490260.pdf.

22 “Bottoms Up: Japan’s Wine Consumption Nearly Quadruples in 30 Years”, Nippon.com, December 25, 2019, https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h00611/bottoms-up-japan%E2%80%99s-….

23 State Statistics Service of Ukraine, "Direct investment (equity capital) from countries of the world to Ukraine economy (2010-2019)", http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua/operativ/operativ2017/zd/inv_zd/pi_ak_ks_reg/….

24 Russian Central Bank, "Direct Investment in the Russian Federation: Positions by Instrument and Partner Country (Asset/Liability Principle)", http://www.cbr.ru/vfs/eng/statistics/credit_statistics/direct_investmen….

25 Fujikura Automotive Ukraine Lviv, LLC and Fujikura Automotive MLD S.R.L.

26 Japan Business Federation – Keidanren, “The 8th Joint Meeting of the Coordinating Council for Economic Cooperation with Japan at the Ministry of Economic Development, Trade and Agriculture of Ukraine and Keidanren”, December 16, 2019, https://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2019/113.pdf.

27 Japan’s ODA budget, even if it had slightly increased in recent years, has decreased almost by half compared to its peak in 1997: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “ODA Budget”, January 24, 2020, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/gaiko/oda/shiryo/yosan.html.

28 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Cabinet decision on the Development Cooperation Charter”, February 10, 2015, https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000067701.pdf.

29 Government of the Republic of Moldova, “Over 100 tractors bought within 2KR project handed over to Moldovan farmers”, July 5, 2018, https://gov.md/en/content/over-100-tractors-bought-within-2kr-project-h….

30 “Gagauzia gets largest share of assistance from EU – research”, infotag.md, April 25, 2018, http://www.infotag.md/rebelion-en/262516/.

31 See the trend of the Japanese ODA budget, which re-bounced in recent years: ODA Budget, op. cit.

32 Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, “Japan: the OSCE’s first Asian Partner for Co-operation”, February 20, 2018, https://www.osce.org/magazine/372946.

33 Embassy of Japan in Ukraine, “Japan’s Assistance to Ukraine”, February 2018, https://www.ua.emb-japan.go.jp/jpn/bi_ua/oda/180205_assistance_en.pdf.

34 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Statement by Parliamentary Vice-Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan, Mr. Kenji YAMADA, Ukraine Reform Conference in Toronto”, July 2, 2018, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/000494960.pdf.

35 Visegrad Group plus Japan Joint Statement, “Partnership based on common values for the 21st century”, June 16, 2013, https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000006466.pdf.

36 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, “Press release on signing of the AA, including DCFTA with Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova”, June 26, 2014, https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/press/danwa/page4_000540.html.

37 European External Action Service, “The Partnership on Sustainable Connectivity and Quality Infrastructure between the European Union and Japan”, September 27, 2019, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/68018/node/68….

38 European Commission and World Bank, “Indicative TEN-T Investment Action Plan”, January 16, 2019, https://www.euneighbours.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2019-01/te….