Almost 20 years ago, an early assessment of the role of the EU in the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons concluded that it performed better at addressing the arms control agenda in multilateral fora than at resolving proliferation crises.1 The reasons for this seemed straightforward: a composite actor like the EU can coordinate better in a multilateral setting, where it is able to rely on ample preparation time, than in the context of international crises that often arise unexpectedly.

A decade after that initial assessment, the situation was the opposite. In 2015, France, Germany and the UK – the E3 – assisted by successive EU High Representatives, secured a deal with Iran after years of painstaking talks alongside the US, China and Russia, putting the EU on the map as a non-proliferation actor. However, in the Review Conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) that took place in the same year, the EU appeared divided in a session that eventually failed to agree a final document.2 How can this evolution be explained – and ideally improved – with a view to the upcoming Review Conference (RevCon) of the NPT in April-May 2020? The present Brief outlines the record of the EU in this context, highlighting the difficulties encountered in the 2015 edition, and identifying the stakes for the EU in the forthcoming RevCon as well as a possible way forward.

The NPT process in trouble

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, in force since 1970, is considered the cornerstone of the nuclear non-proliferation regime. With 191 states parties, it is one of the most universal treaties. Implementation is assessed by states parties in quinquennial review cycles preceded by Preparatory Committees (PrepCom) in the three previous years. The review concerns the three pillars of the treaty: the commitment by the P-5, or nuclear weapons states (NWS), to ‘pursue negotiations (…) on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race (…) and to nuclear disarmament’; the commitment by non-nuclear weapon states (NNWS) to forego the acquisition of nuclear arsenals and to accept safeguard and verification measures; and the promotion of peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

The present decade started well for nuclear arms control. US President Barack Obama set out the goal of nuclear abolition, ‘Global Zero’, in a 2009 speech.3 The US Nuclear Posture Review published the following year outlined steps to reduce Washington’s reliance on nuclear weapons. The NPT RevCon 2010 closed with a final document, and agreed a 64-point Action Plan that covered all three pillars of the Treaty. It also decided to appoint a facilitator to advance the creation of a zone free of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) in the Middle East, an Egypt-sponsored idea endorsed by the 1995 RevCon. However, these encouraging developments were soon overshadowed by stagnation in the implementation of the Action Plan, aggravated by plans by some NWS to modernise their nuclear arsenals.

Regrettably, the 2015 RevCon resulted in a setback. The planned WMD-free zone in the Middle East precipitated the sharpest controversy; however, the lack of progress in the disarmament pillar also proved unusually divisive. Observers pointed to a shrinking of the traditional middle ground between the increasingly polarised camps of the NWS and abolitionists.4 The latter assembled around the so-called ‘Humanitarian Initiative’, which, transposing the logic of unacceptability applied to other WMD, aimed at prohibiting and eventually eliminating nuclear weapons. After the 2015 RevCon, the Humanitarian Initiative coalesced into a treaty: 122 states negotiated the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), or ‘Ban Treaty’, under the aegis of the United Nations (UN). After it opened for signature in September 2017, it became the third most ratified treaty within its first year of existence.5 However, the North Atlantic Council (NAC), along with the P-5 and other umbrella countries, denounced it as a danger to the NPT regime.6 Today, the Ban Treaty is still fifteen ratifications short of the number required for it to enter into force.

The EU has a long history in the NPT process. The level of member state coordination is remarkable in view of the diversity that characterises attitudes in European capitals towards nuclear weapons.

Until early 2020, the Union counted two official nuclear powers among its members, France and the UK.

As members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the majority of EU countries are covered by extended deterrence, in the form of the Atlantic Alliance’s ‘nuclear umbrella’. Several of them – Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy and the UK – host US nuclear weapons on their territory. Cyprus, Finland, Malta and Sweden are neither NATO allies nor are they formally covered by any nuclear umbrella.7 Two further members in this situation, Austria and Ireland, are resolute advocates of nuclear disarmament and have played a key role in the promotion of disarmament treaties: the NPT originated from an Irish-sponsored resolution at the UN General Assembly, while Austria championed the Humanitarian Initiative. With the sole exception of Cyprus, all non-NATO EU countries collaborate with the Atlantic Alliance under the Partnership for Peace programme. On account of the diversity of attitudes among EU members towards nuclear deterrence, the Union was described as a ‘laboratory of consensus’8, apt to agree measures likely to attract advocates in the NPT context.

With the adoption of the EU Strategy against the Proliferation of WMD9 in 2003, non-proliferation activity became broader and more sophisticated.10 The European Security Strategy (ESS) identified WMD proliferation as ‘potentially the greatest threat to our security’.11

The European Security Strategy (ESS) identified WMD proliferation as ‘potentially the greatest threat to our security’.

In the 2016 Global Strategy, it remains ‘a growing threat to Europe and the wider world’.12 EU engagement in this field was aided by the creation of a dedicated line within the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) budget, in addition to pre-existing funding from the Community budget.

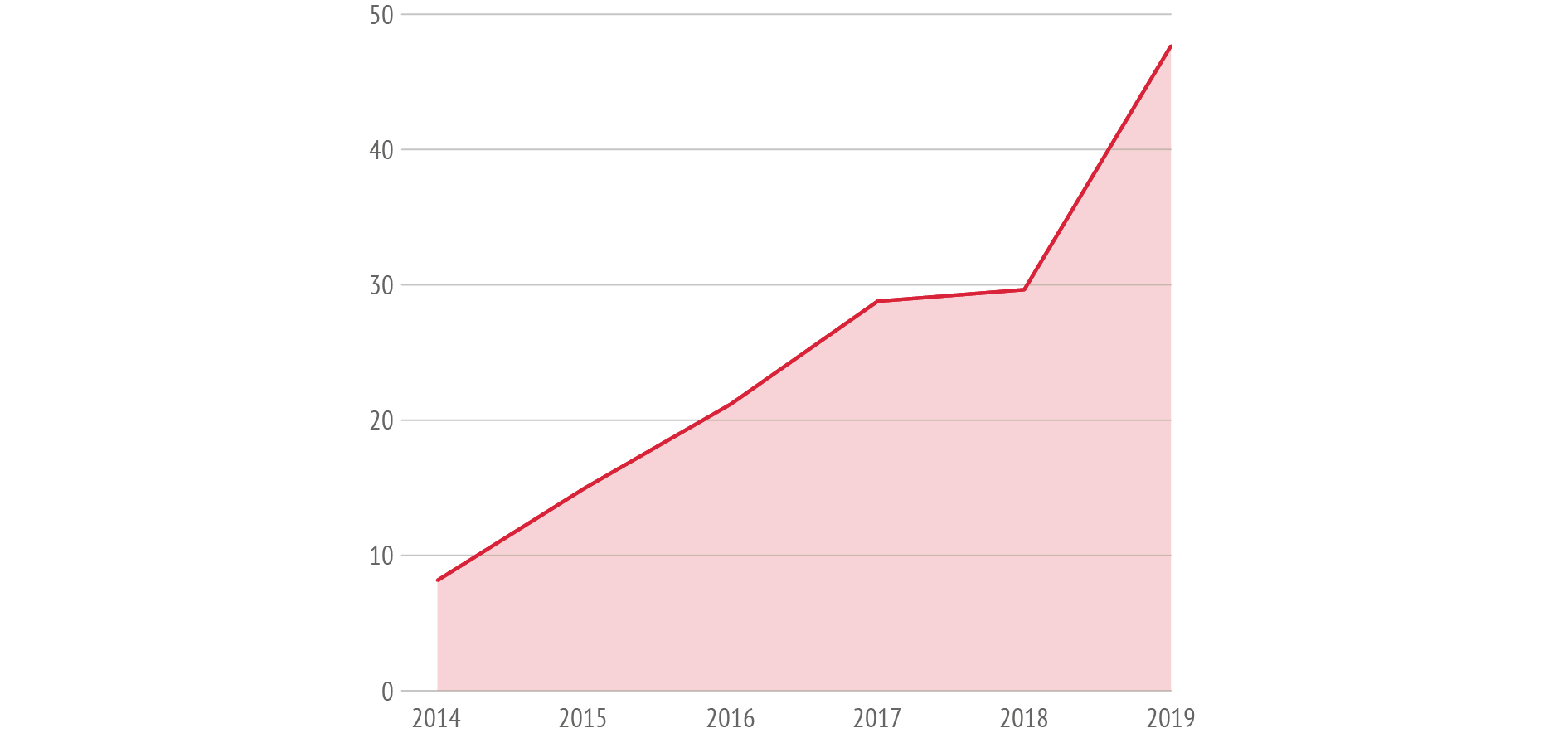

CFSP non-proliferation budget

Amounts committed,2014-2019, € million

Figures as of 05/12/2019

Data: European External Action Service, 2019

While the EU has been generously funding threat reduction assistance, bilaterally and via the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), its role goes beyond financial support. The ‘New Lines of Action’ agreed in 2008 prioritised the universalisation of international agreements and reinforcing compliance.13 Since 2010, the EU has funded the activities of the EU Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Consortium, a network of European think tanks.14 The High Representative’s role in facilitating the nuclear talks with Iran helped to boost the EU’s profile in the field.15 In recent years, the EU has been acknowledged sometimes as a ‘supporting’ actor, sometimes as a fully-fledged or ‘normal’ actor in non-proliferation.16

EU coordination ahead of NPT meetings

EU members traditionally coordinate their positions in preparation for NPT RevCons as part of the CFSP. Coordination in the run-up to the 1995 RevCon, which was to decide on the treaty’s indefinite extension, saw EU member states orchestrating démarches with third countries that consolidated support for extension.17 Over the four review cycles that took place from 1995 to 2015, the EU adopted CFSP legal acts invariably committing it to ‘help build a consensus’ and ‘strengthen the international nuclear non-proliferation regime by promoting the successful outcome of the conference’.18

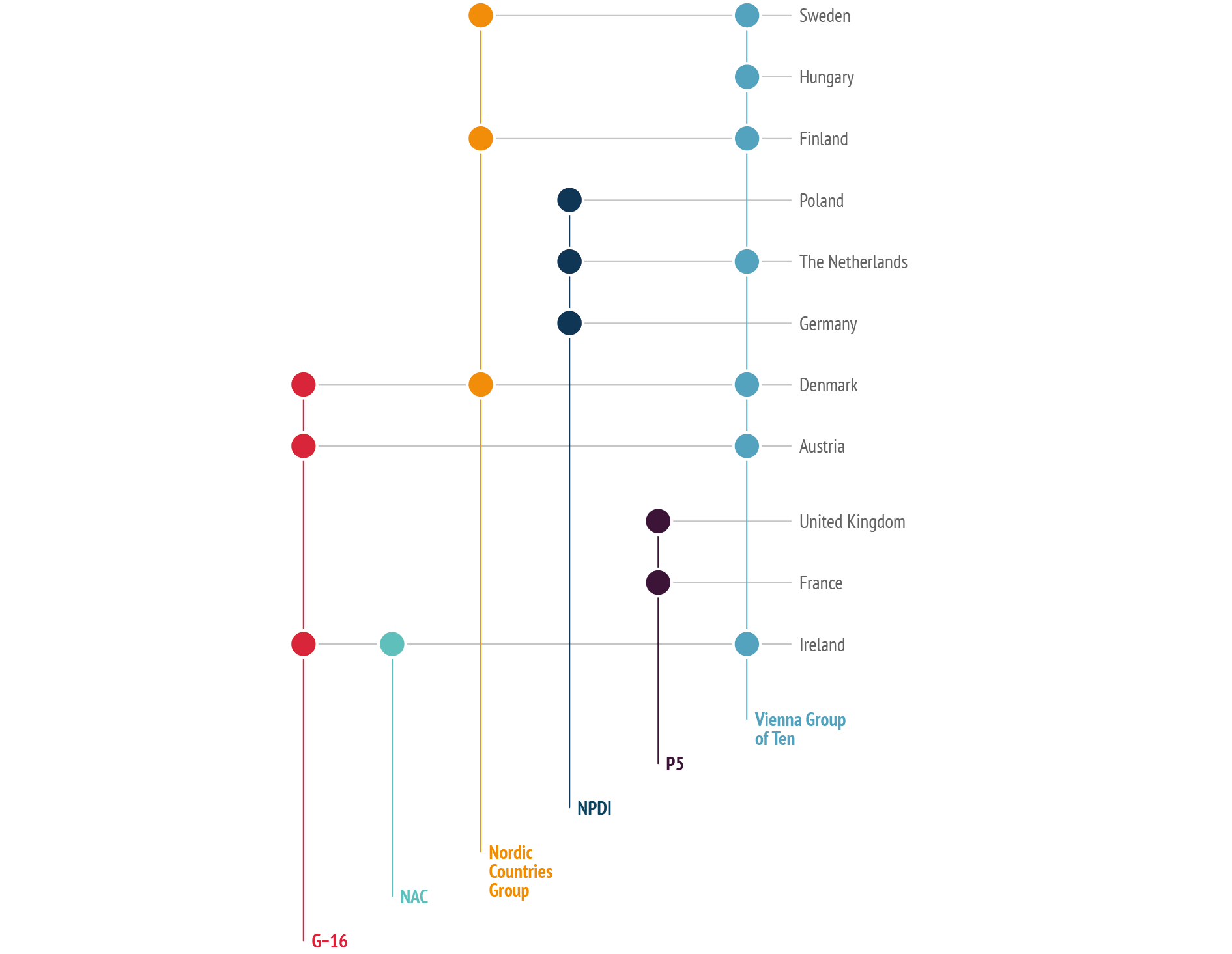

The modus operandi of the EU in the NPT forum combines member states’ individual activity with participation in various groupings in addition to the EU bloc. The NPT is characterised by the presence of multiple groupings: traditional clusters like the 120-strong Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) or the NWS/P-5, or regional groups like the Arab League or the EU. Traditional blocs coexist with yet other like-minded formations, mostly of a cross-regional and/or cross-factional character, which are often in flux. Previous review cycles saw the action of Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy, alongside Norway, under the ‘NATO-5’, a coalition of ‘umbrella’ countries. While this formation is now defunct, the Netherlands and Germany have joined, alongside Poland, the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Initiative (NPDI), a group close to Washington aspiring to play a bridge-building function.19 Concurrently, the Netherlands is part of the Vienna Group of Ten alongside Austria, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Ireland and Sweden.20 Meanwhile, the pro-disarmament New Agenda Coalition (NAC) was launched with three European members, Ireland, Slovenia and Sweden, out of which only Ireland remains.21 Recently, Denmark, Finland and Sweden formed a Nordic Countries group alongside non-EU members Norway and Iceland. Thus, EU states have navigated this shifting landscape by combining memberships in partially overlapping groupings, while acting separately in a national capacity. In thematic terms, the EU has maintained unity by prioritising collective action in the non-proliferation and peaceful uses pillars of the NPT, to the detriment of the disarmament pillar, where traditional divisions among nuclear possessors and disarmament advocates hamper consensus.

The deteriorating arms control environment

While in the past decade attention focused on the proliferants North Korea and Iran, the current review period is characterised by the dismantling of the arms control treaty network. The first months of 2019 witnessed the denunciation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty by the United States, following allegations of Russian non-compliance. The New Strategic Arms Reduction (START) Treaty is at risk of not being renewed after it expires in February 2021. The Treaty on Open Skies is similarly in jeopardy. The strengthening and universalisation of multilateral arms control agreements is dogged by stagnation. Adherence to the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), open for signature since 1996, is still missing eight ‘Annex 2’-signatories required for its entry into force. Moreover, no new Annex 2-country has acceded since 2008.22 The negotiation of a Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty remains out of sight. The NPT RevCon 2020 will take place against a backdrop that has not looked so inauspicious since the EU became active in arms control.

The NTP framework was also left in bad shape after the 2015 RevCon, which saw the acclaimed 2010 Action Plan as well as the initiative for a WMD-free zone in the Middle East unravel. At the opposite end of the spectrum, shortly after the RevCon, negotiations on the Ban Treaty started. Thus, the NPT framework is stretched between two increasingly polarised camps: NWS resisting moves towards disarmament and nuclear abolitionists. The ‘radicalisation of the nuclear disarmament debate’23 has shrunk the overlap between both camps, reducing the middle ground occupied by advocates of a gradual approach towards nuclear disarmament.

This bleak picture leaves the EU faced with a multi-faceted challenge: firstly, the erosion of nuclear arms control undermines its objective of upholding the NPT and multilateralism, a leitmotiv of both the ESS and the Global Strategy, at a time when the multilateral system is under strain. The denunciation of arms control treaties affects Europe directly: albeit concluded between the Washington and Moscow, they protect primarily European territory. The current challenges to the NPT framework, although global in character, are of specific concern to the bulk of EU members which occupy the shrinking middle ground of advocates of a gradual approach to disarmament. In the aftermath of the 2015 debacle, observers referred to the EU as ‘caught in the middle’ or ‘stuck on disarmament’.24 All this puts the EU in the spotlight: if it fails to frame a response to protect the NTP process, it risks losing its hard-won relevance to the non-proliferation regime and reverting to the uncomfortable role of a ‘payer rather than player’, to borrow a phrase that has been used to describe EU efforts to defuse the North Korean nuclear crisis.25

Meanwhile, the EU’s main success in the non-proliferation arena to date, the Iran deal, is on the verge of collapse. Washington’s withdrawal and its re-imposition of sanctions has severely endangered its viability. The EU has gone to great lengths to rescue it: it revived its 1996 blocking statute,26 and in 2019 Berlin, London and Paris established the Instrument for Supporting Trade Exchanges (INSTEX) to facilitate transactions with Iran. Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden recently joined as shareholders.27 While these initiatives indicate a willingness to salvage the Iran deal, in opposition to the posture of the EU’s principal ally, the private sector holds back under the threat of US sanctions. In response to Tehran’s resumption of enriched uranium production, the EU recently triggered the conflict resolution mechanism.29

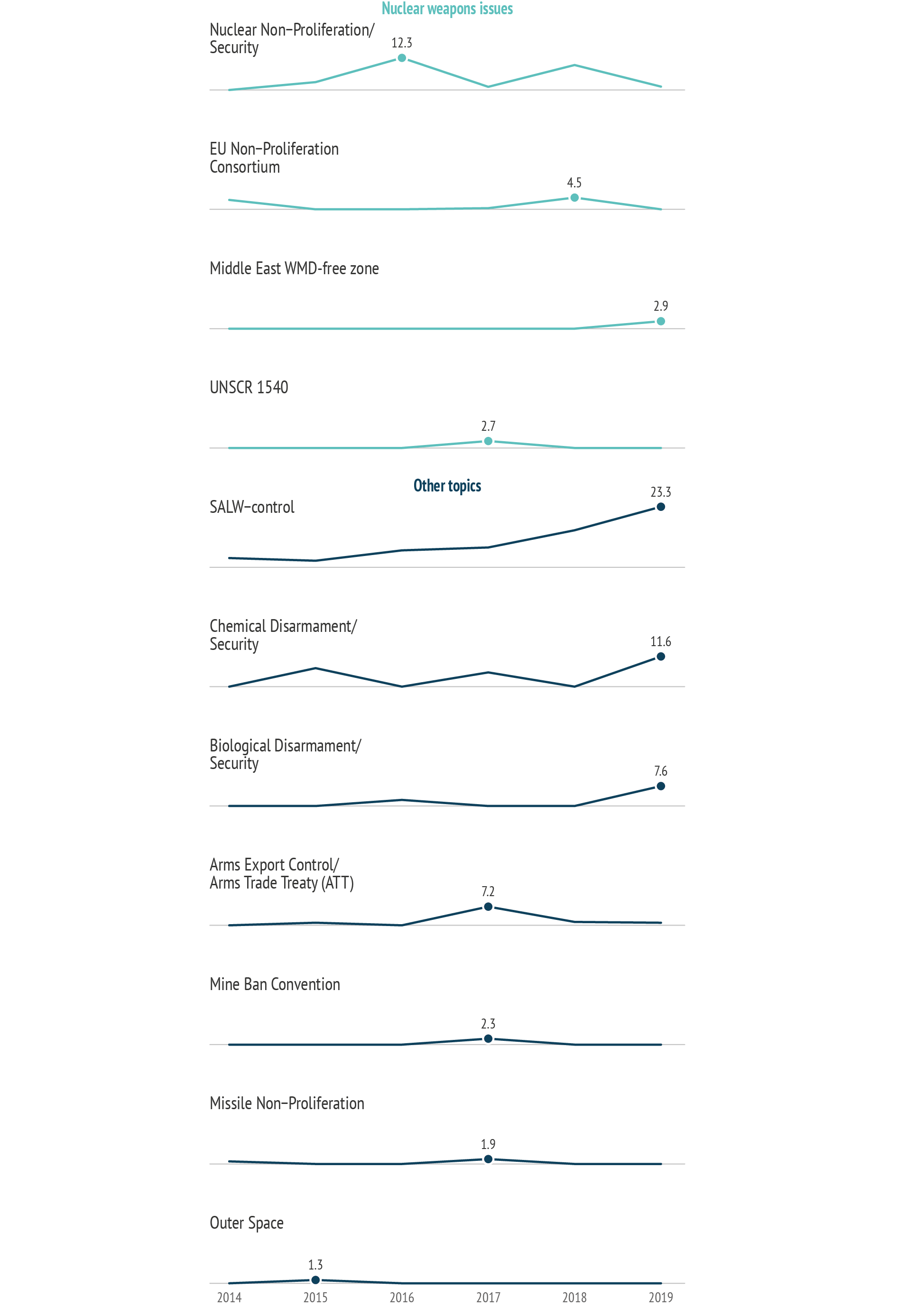

CFSP non-proliferation budget per topic

Amounts committed, 2014-2019, € million

Figures as of 05/12/2019

Data: European External Action Service, 2019

The EU’s NPT challenge

Beyond the deterioration of global arms control, the EU’s reputation and credibility as a security actor is at stake. Over the 15 years between the 1995 NPT extension and the 2010 review, the EU established increasingly successful coordination: it invariably entered the RevCons with a common position in place, made statements at both the Plenary and the Main Committees, and submitted working papers. The sophistication of the CFSP documents adopted in preparation for the sessions illustrate this evolution. The CFSP legal acts that preceded the 1995 and 2000 reviews consisted of merely one substantive page. By contrast, the 2005 Common Position featured a catalogue of four substantive pages, while the 2010 Common Position reached a peak of six.30 Equipped with a robust common position, the EU presented statements and working papers across all pillars of negotiation at the 2010 RevCon. In contrast, in the 2015 RevCon, the Humanitarian Initiative proved so divisive that the Council could not agree on a CFSP act. Instead, it reflected vague priorities in non-binding conclusions, demonstrating the existence of unresolved disagreement. Symptomatic of the discord within the EU was the parallel failure of the European Parliament to draft its own priorities for the 2015 RevCon. In consequence, the failed 2015 RevCon witnessed the weakest performance of the EU to date. Beyond the presentation of ‘a few statements and working papers’, its action remained with ‘little to no impact’.31

The cleavage within the EU reflects the split that characterises the NPT community, rooted in the dissatisfaction with the pace of implementation of the disarmament requirement by NWS that catalysed the Ban Treaty in the aftermath of the 2015 RevCon. Although some initial supporters like Sweden decided against accession, the TPNW counts Ireland among its 80 signatories and Austria among its 35 parties.32

EU members in NPT cross-regional coalitions

Revitalising the EU at the NPT

In view of the 2015 debacle, how can the EU rebuild its credibility with a view to the upcoming NPT RevCon? Last year, the EU committed to fund a series of seminars under the aegis of the UN Office of Disarmament Affairs (UNODA) with the purpose of raising awareness and helping delegations prepare for the session. By increasing opportunities for information and dialogue, this initiative might aid consensus-building in the run-up to the RevCon. However, the revitalisation of the EU’s role in an NPT forum under stress necessitates a bold, innovative approach to patch up divisions among a polarised membership. Reconsidering some premises of EU engagement can help it adjust to a transformed NPT environment.

A new modus operandi

As part of the CFSP, the EU aspires to present itself as a unitary actor by coordinating its positions and voting jointly in international fora.33 Over the years, projecting an image of relative unity has represented a major accomplishment given that nuclear deterrence remains one of the most divisive issues in the CFSP. Voting behaviour at the UN General Assembly reveals that nuclear and disarmament issues rank among the most controversial among EU members, with the European nuclear powers and non-NATO members often voting differently from the EU mainstream.34 The EU’s modus operandi at the NPT combines the hammering out of a common stance with member state action in like-minded groupings, allowing members to promote their views beyond the EU consensus. The flexibility of this approach makes it possible for the EU to appear as a cohesive entity while member states can keep their affiliation to other groupings. Moreover, this flexibility has made it possible to accommodate the alignment of third countries, turning the EU into a veritable regional group representing Europe rather than just its members.

While this modus operandi served the EU well for 20 odd years, the price to be paid for a common EU stance was to remain silent on disarmament. Maintaining consensus was only possible by sidelining the disarmament question in favour of the other pillars, where more common ground existed among member states. At the same time, simultaneous participation of some members in like-minded coalitions weakened the EU’s image as a bloc when their statements deviated from the EU common stance.35 The discord witnessed over the Humanitarian Initiative eventually interrupted the incremental pattern of EU coordination, suggesting that the current modus operandi might have exhausted its usefulness. What could the way forward look like?

The principal objective of the EU is to promote a successful outcome of the NPT session, and preserve the NPT altogether. This objective can be best achieved by following a policy of framing common statements and submissions selectively. As evidenced by the sheer number of statements produced at multilateral arms control fora in Geneva, New York, The Hague and Vienna – no less than 192 in 2019 – the EU coordination machinery accomplishes a remarkable job. Systematic efforts to agree common stances and vote jointly in international fora constitute a salutary exercise, resulting in the framing of common approaches that would not come about otherwise. This endeavour enables the EU to discern where agreement is within reach and where not, ensuring that no items escape consensus for any other reason than unbridgeable divisions. The practice of intra-EU coordination should continue unabated.

The principal objective of the EU is to promote a successful outcome of the NPT session, and preserve the NPT altogether.

Yet, EU tactics should depend on the outcome of this coordination effort. The EU should act as a grouping only in issue areas where EU member states are in strong agreement on ideas that can promote progress in the field. The 2005 working paper discussing modalities for NPT withdrawal exemplifies an EU contribution providing added value.36 However, where this cannot be achieved, common statements do little for the image of the EU as a unitary bloc. On the contrary, such an image is undermined when ‘lowest common denominator’ statements coexist with member state positions that point in opposite directions. Where EU agreement is reduced to the ‘lowest common denominator’, the EU could follow a policy of systematically supporting the groupings that promote the middle ground, currently the NPDI as well as the Vienna Group of Ten. By aligning with these cross-regional coalitions of umbrella countries, the EU will strengthen the moderate faction that lost ground after 2010. Thanks to the overlapping membership of the Netherlands, Germany and Poland in the NPDI and five additional EU countries in the Vienna Group of Ten, the EU can encourage an agenda of gradual progress towards disarmament. This serves the objective of preserving the NPT without hurting EU visibility. After all, while regional and like-minded groupings co-exist in the NPT forum, regional blocs rarely call the shots.37 The most established clusters, such as the P-5 and NAM, and the most influential like-minded groups, such as NAC, are notoriously cross-regional. Regional groupings matter in the NPT context primarily when they address their geographical area directly, as exemplified by the Arab League’s advocacy of a WMD-free zone in the Middle East. At the RevCon 2020, the EU could work together with the NPDI and its adepts to reach out to NAM members, revive what can be salvaged of the 64-point Action Plan, and rebuild the middle ground in the NPT community.

A modus vivendi with the Ban Treaty

The EU could benefit from acknowledging the turning point that the Ban Treaty entails for the NPT process, and developing a modus vivendi with it. Discord over insufficient progress towards disarmament might well have precipitated the failure of the RevCon had the Middle East issue not done so before. Intra-EU divisions became acute to such an unprecedented degree that this precluded the framing of a common approach both before and during the session.

On account of the predominance of umbrella countries among its members, the EU position on disarmament in the 2015 RevCon leaned more towards the stance of European NWS than towards the Humanitarian Initiative. The Council Conclusions on the 2015 RevCon employed language resonating with the approach of France and the UK, which shifts responsibility for further stockpile reductions to the US and Russia: ‘The Council welcomes the considerable reductions made so far taking into account the special responsibility of the States that possess the largest arsenals […] and strongly encourages them to seek further reductions in their nuclear arsenals.’38 By contrast, allusions to the Humanitarian Initiative distance the EU from it: ‘The Council further notes […] the ongoing discussions on the consequences of nuclear weapons, in the course of which different views are being expressed, including at an international conference organised by Austria, in which not all EU Member States participated’. Abnormally for a Council statement, the emphasis on the lack of universal EU attendance at the meeting undermines the message of EU unity.

The cleavage evidenced by these statements show that the EU is not functioning as the laboratory of consensus that it was once claimed to be. This probably owes much to the change in the ‘demographics’ of the organisation. After the phrase was popularised, the Eastern enlargement process brought into the EU a large number of umbrella countries, which strengthened a conservative approach to disarmament. This shift accentuated the difference between the mainstream orientation in the EU and that in the NPT community, which is more favourable to abolition. The disjoint between the preferences of EU and NPT memberships deepened.

The EU is not functioning as the laboratory of consensus that it was once claimed to be.

Now that the TPNW is approaching its entry into force, it appears less threatening to the NPT than many anticipated: the TPNW does not rival the NPT in terms of the number of signatories. The NPT is almost universal, while the TPNW has not yet reached the 50 ratifications necessary for its entry into force. To date no TPNW party has withdrawn from the NPT. TPNW members continue to be active members of the NPT and to support its aims, and there are no signs so far that the TPNW may ‘hijack’ the NPT process. Many observers argue that a treaty banning nuclear weapons is not in conflict with the NPT.39 However, the debate over the compatibility of the Ban Treaty with the NPT ultimately misses the point. Whether the Ban Treaty will complement or undermine the NPT is not a given: it will depend on how parties of each forum frame the relationship towards each other.

Rather than vilifying the TPNW as a competitor to the NPT, the EU could reconcile itself with advocates of the former by recognising the legitimacy of its ultimate objective, which is equally enshrined in the NPT. Other than having engaged no less than 122 states at the negotiating table, the Ban Treaty enjoyed the support of an NGO coalition, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, which was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Acknowledging the Ban Treaty as an expression of widespread frustration at the pace of nuclear disarmament constitutes a constructive basis for rebuilding a common agenda that engages the entire NPT community. The EU would do well to interpret the Ban Treaty as an impulse to move towards elimination, and work with its parties towards what is sorely missing from both the TPNW and the NPT frameworks: a viable plan to work towards nuclear disarmament accompanied by its gradual implementation.

References

- Clara Portela, “The role of the EU in the non-proliferation of nuclear weapons”, PRIF Report no. 65, 2003.

- Michal Smetana, “Stuck on Disarmament: The European Union and the 2015 NPT Review Conference”, International Affairs, vol. 92, no. 1, 2016, pp. 137-52.

- Remarks by President Barack Obama, Hradcany Square, Prague, 5 April 2009, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president…

- Oliver Meier, “The 2015 NPT Review Conference Failure: Implications for the Nuclear Order”, Working Paper 4, Stiftung Wissenschaft and Politik (SWP), 2015.

- Michal Onderco, “Nuclear Ban Treaty: Sand or Grease for the NPT?”, in Tom Sauer, Jorg Kustermans and Barbara Segaert (eds), Non-Nuclear Peace: Beyond the Nuclear Ban Treaty (Basingstoke: Palgrave McMillan, 2020), pp. 131–48.

- North Atlantic Council Statement on the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, September 20, 2017, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_146954.htm?selectedLocale=en

- Manuel Lafont, Tara Varma and Nick Witney, “Eyes tight shut: European attitudes towards nuclear deterrence”, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), December 2018.

- Camille Grand, « L’Union européenne et la non-prolifération des armes nucléaires », Cahier de Chaillot no. 37, Institut d’Etudes de Sécurité de l’Union de l’Europe occidentale, January 2000, p. 47.

- Council of the European Union, “EU strategy against the proliferation of Weapons of Mass Destruction”, December 2003, https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/st_15708_2003_init_en.pdf.

- Clara Portela and Benjamin Kienzle, “EU non-proliferation policies before and after the 2003 strategy”, in Spyros Blavuokos, Dimitris Bourantonis and Clara Portela (eds), The EU and the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (Basingstoke: Palgrave-MacMillan 2015), pp. 48-66.

- Council of the European Union, “European Security Strategy. A secure Europe in a better world”, December 2003, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/30823/qc7809568enc.pdf.

- Council of the European Union, “Shared Vision, Common Action: A stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign And Security Policy”, June 2016, p.41, http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/top_stories/pdf/eugs_review_web.pdf.

- Council of the European Union, “New lines for action by the European Union in combating the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and their delivery systems”, December 2008, http://register.consilium.europa.eu/doc/srv?l=EN&f=ST%2017172%202008%20…

- Council Decision 2018/299 of 26, February 2018 promoting the European network of independent non-proliferation and disarmament think tanks in support of the implementation of the EU Strategy against proliferations of weapons of mass destruction, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32018D029…;

- Clara Portela, “The EU’s evolving responses to nuclear proliferation crises”, Non-Proliferation Papers no. 46, EU Non-Proliferation Consortium, Stockholm, 2015.

- Riccardo Alcaro and Aniseh Tabrizi, “Europe and Iran’s Nuclear Issue: The labours and sorrows of a supporting actor”, International Spectator vol.49, no.3, 2014, pp. 14-20; Ramon Pacheco, “Normal power Europe: non-proliferation and the normalisation of EU foreign policy”, Journal of European Integration, vol. 34, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1-18.

- David Fischer and Harald Müller, “United Divided. The Europeans and the NPT Extension Conference”, PRIF Report no. 40, 1995.

- Council Common Position 2005/329/CFSP relating to the Review Conference on the Treaty on the NonProliferation of Nuclear Weapons of 2005, art. 1 and 2.

- Extra-European members include Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Mexico, Nigeria, Philippines, Turkey and UAE.

- Extra-European members include Australia, Canada, New Zealand and Norway.

- Extra-European members include Brazil, Egypt, Mexico, New Zealand and South Africa.

- Data by Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organisation, https://www.ctbto.org/the-treaty/status-of-signature-and-ratification/

- Op. Cit., “The 2015 NPT Review Conference Failure: Implications for the Nuclear Order.”

- Ibid; Op. Cit., “Stuck on Disarmament: The European Union and the 2015 NPT Review Conference.”

- Axel Berkofsky, “The European Union in North Korea: Player or only payer?”, Policy Brief 123, ISPI, 2009.

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2018/1100 of 6 June 2018 amending the Annex to Council Regulation (EC) No 2271/96, C/2018/3572; Sascha Lohmann, “Extraterritorial U.S. Sanctions”, SWP Comment no. 5, SWP, February 2019.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, “Joint statement on joining INSTEX by Belgium, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden”, November 29, 2019.

- Elizabeth Rosenberg, “The EU can’t avoid U.S. sanctions on Iran”, Foreign Affairs, October 2018.

- “Europeans trigger dispute mechanism in urgent bid to save Iran nuclear deal”, BBC News, January 14, 2020.

- Council Decision 94/509/CFSP; Council Common Position 2000/297/CFSP; Council Common Position 2005/329/CFSP and Council Decision 2010/212/CFSP.

- Megan Dee, “The EU’s performance in the 2015 NPT Review Conference: What went wrong”, European Foreign Affairs Review, vol. 20, no. 4, 2015, pp. 591–608.

- United Nations Treaty Collection, ‘Chapter XXVI – Disarmament ‘, (9. Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons), New York, July 7, 2017, https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVI…;

- Council Decision 2019/615/CFSP of 15 April 2019 on Union support for activities leading up to the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32019D061…;

- Paul Luif, “Der Konsens der Staaten der Europäischen Union in der Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik“, in Johann Frank and Walter Matyas (eds), Strategie und Sicherheit 2014 (Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2014), pp. 289–303.

- Op. Cit., “The EU’s performance in the 2015 NPT Review Conference: What went wrong”; Op. Cit., “Stuck on Disarmament: The European Union and the 2015 NPT Review Conference.”

- Op. Cit., “The EU’s performance in the 2015 NPT Review Conference: What went wrong”; See UNODA, “Withdrawal from the NPT: European Union common approach”, NPT/CONF.2005/WP.32, 2005.

- Megan Dee, “Group Dynamics and Interplay in UN Disarmament Forums: In Search of Consensus”, Hague Journal of Diplomacy, vol. 12, 2017, pp. 158-77.

- Council Conclusions on the Ninth Review Conference of the Parties to the NPT, CFSP 61, 2015, p.3.

- See for example Tariq Rauf, “The year in which nuclear weapons could be banned?”, SIPRI Commentary, March 20, 2017.