The crisis in Yemen epitomises the complexity of contemporary intra-state conflicts: rather than a simple, binary war, the situation is characterised by various layers of conflict with multiple state, hybrid, non-state actors and foreign state powers playing active roles. Analysts and policymakers need to be aware of this complexity in order to grasp the drivers and implications of this war, and identify possible avenues for conflict resolution.

Yemen matters a lot for the strategic interests of the EU: its Western waters are the southern frontier of the Mediterranean Sea. But Yemen has also become an arena of strategic competition for the Gulf and Middle Eastern state powers, who have constructed or taken over control of ports, military bases and airports along its coasts and islands as a springboard for projection in the Western Indian Ocean. Finally, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), established in 2009 and based in Yemen, remains one of the most entrenched and resilient jihadi networks in terms of local ties and political adaptability.

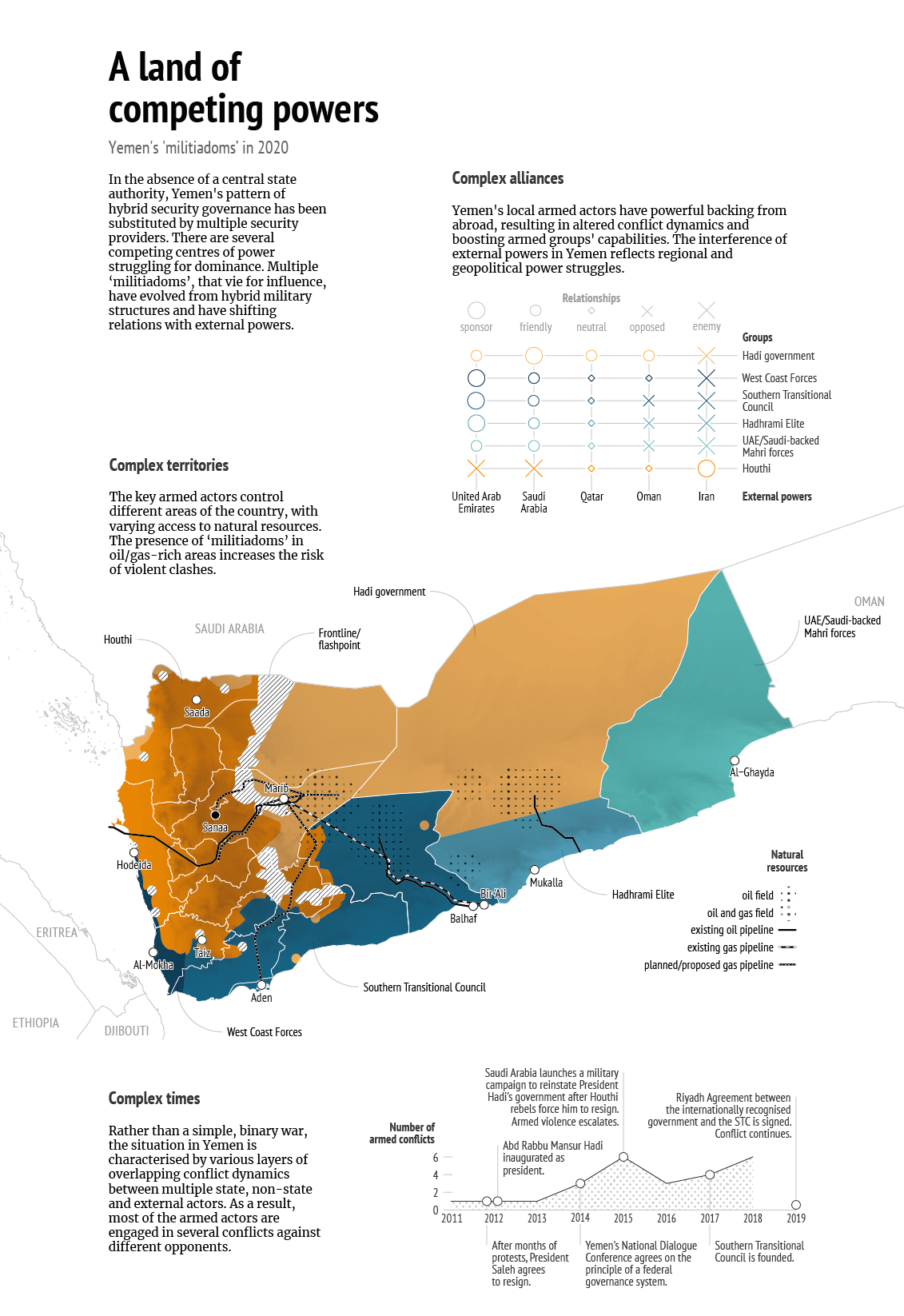

This Conflict Series Brief analyses the intertwined layers of conflict in Yemen and their implications for war resolution efforts. The local-foreign nexus between Yemini and external actors needs to be disentangled to separate domestic drivers and the regional and/or sectarian dimensions of the conflict. Competing ‘militiadoms’ are on the rise, thus transforming the traditional Yemeni pattern of hybrid security governance into a multiple security governance scenario. The Brief examines the Yemeni crisis in all its complexity, focusing on existing and emerging dynamics. Interference by foreign state powers is both a cause and a consequence of the protracted conflict, while the potential for peace must be sought at local level. This approach will help to identify strategies for mitigating and possibly resolving the crisis.

Four intertwined layers of conflict

The war in Yemen derives from long-standing grievances, related to the exclusion of segments of the population from the country’s political and military structures and the unequal redistribution of national wealth and resources. After the reunification of the country in 1990, horizontal inequalities between northerners and southerners added to the chronic vertical inequalities between the ruling northern elite and the rest of the population.1 The ongoing war comprises four intertwined conflicts. First, it is a war of attrition between the political centre (the capital Sanaa) and the marginalised peripheral regions (the north, now controlled by the Houthis, the Zaydi Shia insurgents; and the secessionist southern regions). Second, it is a power struggle between old and new elites: in 2014-5, the political-military-tribal bloc still loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh and part of the power-sharing government, forged an alliance with the Houthis, thus derailing the post-2011 transitional institutions headed by Abd Rabbu Mansur Hadi (Saleh’s former vice president) and the Islamist Islah party (comprising the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafi militants). Third, the conflict has become a theatre for regional rivalry between the Saudis and the Iranians and, to a lesser extent, for influence in the south between the contending allies Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Fourth, the protracted war has activated sectarian tensions (Sunni vs Shia) which are unusual in the Yemeni social context, given the degree of cultural and doctrinal convergence between the local Zaydi Shia and Shafei Sunni communities. This sectarian dimension has been fuelled by the interference of Saudi Arabia and Iran and their blaming of each other for supporting, respectively, Salafi groups and the Houthis, denigrated as ‘takfiriyyin’ (‘infidels’) and ‘safavids’ (‘Persians’) by their opponents.

Alliance-making is usually dictated by pragmatic short-term interests rather than ideological and sectarian loyalties.

The dispute between the centre and the peripheries and the struggle between old and new elites constitute the original drivers of the Yemen conflict, while the Saudi-Iranian regional competition and the sectarian factor represent geopolitical implications of the war. Therefore, defining the war first and foremost as a proxy dispute between Saudi Arabia and Iran is short-sighted and misleading, as is interpreting the crisis through sectarian lenses. Conflict analysis is complicated by Yemen’s tribal and political alliances, which are traditionally fluid and changing: alliance-making is usually dictated by pragmatic short-term interests rather than ideological and sectarian loyalties. For instance, in 2004-10 Saleh waged six wars against the Houthis in Saada governorate (the insurgents’ stronghold) and neighbouring areas, but then allied with the Houthis against the transitional institutions to (re)gain power, breaking their alliance again in late 2017 when Saleh was killed by Houthi militants. Saudi Arabia supported Saleh’s regime for more than 30 years despite the president being a Zaydi Shia; Saudi Arabia and the UAE have backed different and often competing Yemeni groups in southern regions of Yemen (the internationally recognised government and pro-Islah elements vs Salafis and secessionists), although they are both Sunni countries. As discussed later in this Brief, this ´never is forever` approach to alliances and alignments in Yemen may yet prove to be a valuable resource for conflict resolution.

Beyond hybridity: militiadoms and multiple security governance

From 2015 onwards, these intertwined layers of conflict have contributed to fragment Yemen’s political-military landscape. As things currently stand, three ‘state’ centres of power coexist in Yemen: the internationally recognised government; the Houthi-led ‘government’ in Sanaa; and the self-proclaimed Southern Transitional Council (STC). As the national framework has disintegrated, local rivalries have intensified, leaving more room to foreign state players for interference in the country. Emerging from the ruins of state institutions, ‘militiadoms’, a militarised variant of ‘chiefdoms’ and ‘sheikhdoms’ (prominent chiefly in the Saada-Sanaa Houthi-held area; the pro-government Eastern Marib province, fiefdom of the vice president and deputy commander of the Yemeni armed forces General Ali Mohsen Al Ahmar; and the pro-STC port city of Mukalla in Hadramawt) have come to play a key role in Yemen’s security governance.2 These are geographically adjacent but disconnected micro-powers, often competing with one another, that have evolved from hybrid military structures and mirror the local power balances prevailing in the respective territories. Yemen’s militiadoms develop socio-economic informal networks which are connected to the competing Yemeni ‘states’: this distinguishes ‘militiadoms’ from areas ruled by warlords which, in contrast, do not aspire to creating an institutional framework and display ‘a neopatrimonialist attitude’.3

The emergence of militiadoms has transformed Yemen’s security governance landscape from one characterised by hybrid security actors to one hosting multiple security actors. Yemen has never been a Westphalian nation-state, where the state holds a clear monopoly of legitimate violence. In Yemen, security governance develops on a continuum between hybridity and multiplicity. Until 2015, hybridity represented the dominant feature of the Yemeni security and military system, reflected in the structural overlapping of tribal and military roles and loyalties (for instance, tribal chiefs who are also military commanders, politicians and businessmen in many cases) and in blurred boundaries between formal and informal security actors (e.g. tribal militias who were legally part of the army, but maintained a certain degree of operative autonomy). The army of post-1990 unified Yemen was supported by tribal auxiliaries, i.e. state-sponsored militias able to strengthen or enforce territorial control and bottom-up loyalty, although the regular army remained the pillar of these hybrid military structures. As shown by Saleh’s regime, security governance needs a single state centre, albeit contested and with a limited monopoly on force, to generate ‘hybridity’: in this system of governance, there is both competition and cooperation between formal and informal security actors and, in case of cooperation, a hybridisation of formal and informal security actors becomes the norm.4

But since 2015 onwards, competing factions with militias at the centre of hybrid military structures have emerged from the ashes of the collapsed regular army, most of them constituting rival militiadoms. In the context of post-2015 competing ‘state’ centres (the internationally-recognised government; the Houthis’ de facto governing authority; the self-proclaimed STC), multiplicity rather than hybridity characterises the current Yemeni pattern of security governance lacking a single state. In fact, multiple and competing post-state security providers are present on the territory, including the remnants of the regular army.5

Foreign state powers have played an important role in fostering the emergence of this multiplicity of armed actors: by backing different militiadoms (formally or informally), they alter conflict dynamics and boost armed groups’ capabilities. For instance, Iran has helped the Houthis to develop indigenous missile and drone expertise; the UAE has trained and equipped southern pro-secessionist militias; Saudi Arabia has supported pro-government sponsored militias. Most of Yemen’s local actors can be considered proxies, since they have developed political, military and financial relations with foreign state patrons.6 Considering that ‘“proxy-ness” exists on a spectrum’ and so manifests itself to varying degrees,7 local actors in Yemen still maintain a certain amount of autonomy vis-à-vis their backers: they have shown themselves to be opportunistic players able to actively capitalise on their relations with these competing external powers in order to strengthen their domestic leverage.

The role of foreign powers in reshaping local politics

Foreign state powers have contributed to the rise of militiadoms, through open intervention or interference in Yemen. But at the same time, the resulting multiple security governance scenario gives these external powers extensive room for manoeuvre, allowing them to enhance their presence or carve out niches of geopolitical influence in the country. Through their intervention foreign state powers have exacerbated Yemen’s fragmentation and are quick to capitalise on this, aiming to gain direct or indirect control of civilian infrastructures, establish military bases/outposts and project their influence over oil and gas-rich areas via local proxies. In fact, external interests and agendas have progressively intertwined with the domestic drivers of the conflict. This local-foreign nexus can be traced in some already existing dynamics (border security governance; control of key civilian and/or military infrastructures) as well as emerging dynamics (the control of oil and gas-rich areas). In all cases, interference by external powers has led to a deterioration in Yemen’s overall security.

Border security governance and civilian/military infrastructure

Due to the interference of foreign state powers, Yemeni borders are now more permeable than in 2015. This is the case despite the growing role that neighbouring states play in security governance (having also deployed troops in border areas) and the militarisation of the borders. The Yemeni-Saudi and the Yemeni-Omani borders demonstrate the negative implications of geopolitical rivalries that compel local actors (for instance, border tribes not aligned with the Houthis and Mahri tribes) to take sides in the conflict to protect their interests.

External interests and agendas have progressively intertwined with the domestic drivers of the conflict.

Along the Yemeni-Saudi frontier, the political and military rise of the Houthis, who have been recipients of Iranian military support especially since 2015, has convinced Saudi Arabia to strengthen its securitisation-first approach. This is a borderland area inhabited by tribes bound by ties of kinship, informal economic exchanges and shared cultural heritage. From 2015 onwards, Riyadh’s attitude has changed from a ‘borderland politics’ to a ‘border politics’ approach: the traditional cooperation and patronage with local tribes has been replaced by the incremental militarisation of the frontier. However, the Houthis have stepped up their asymmetric warfare against Saudi territory and infrastructure (with missile and drone strikes) since Riyadh’s military intervention. This suggests that the Saudis’ militarisation strategy was counterproductive and triggered further insecurity at the border.

The Yemeni-Omani border has turned into an arena of geopolitical confrontation among the formal allies UAE, Saudi Arabia and Oman. This has resulted in local discontent and rising instability in the eastern region of Mahra: an area hitherto untouched by violence, with no Houthi presence and where jihadi activity and influence had made only limited inroads until very recently. Therefore, this regional competition has exported instability into one of the few stable corners of Yemen, which traditionally relied on tribal self-governance. In late 2017, Saudi Arabia sent military forces to Mahra to tackle border and arms smuggling from Iran.

In reality, Riyadh’s primary concern was to counter the expansion of the Emiratis who, having initially provided development aid to the region, have subsequently focused on military build-up along this strategic coast. The Emirati-Saudi presence in Mahra triggered a response from Oman, who stepped up financial support to loyal Mahri tribes to preserve its influence. The Sultanate has close links with Mahra which shares human and economic connections with the neighbouring Dhofar region in Oman. Since 2018, Muscat has reportedly been supportive of the intermittent Mahri protests against the Emirati and Saudi interferences in the governorate.

Data: GADM, 2020; Natural Earth, 2020; Chatham House, 2019; PRIO, 2007; Petroleum Economist, 2017; UCDP, 2020

Alongside these recently emerged border dynamics, international interference has led to increasing foreign control of strategic infrastructures in Yemen. For instance, the Saudis now control the main civilian infrastructure facilities of Mahra (al-Ghayda airport and Nishtun port) and have established several military outposts in the governorate. The Saudis hope to construct a pipeline in Mahra that would allow them to transport their oil directly to the Arabian Sea, thus bypassing the Strait of Hormuz. The remote and UNESCO-protected island of Socotra, far from the mainland and from armed clashes, is also now at the centre of a geopolitical dispute between the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The Emiratis sent humanitarian aid to the island and funded development projects in the aftermath of the 2015 cyclones which wreaked extensive damage.

But in 2016-18 the UAE also began to take control of the local airport, established training facilities to organise local militia forces, and deployed separatist troops from the mainland. In 2018, as locals - with the backing of island authorities - staged protests against the Emirati presence, Saudi Arabia sent troops to defuse tensions. The UAE has since allegedly reduced the number of military personnel on the island: but Saudi forces remain, with Riyadh launching a series of development projects for Socotra, too. The UAE has recently been expanding the port of Hadiboh to host bigger ships. In this context of competition for influence, Oman tries - as in the case of Mahra - to protect its traditional linkages with the island which was part of the Mahra Sultanate of Qishn and Socotra until 1967. In so doing, Muscat supports Socotri tribal leaders who have ties with Mahra and oppose the Emirati and Saudi presence. This indirect rivalry for influence and infrastructures is reshaping the contours of local politics and hampers local cohesion. For instance, the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Oman now have local backers in Socotra who support competing narratives on ‘reconstruction' and 'development’, leading to polarisation among the local community.

Contested power balances in oil/gas-rich areas

Unlike the conflict dynamics that have already materialised, the presence of external powers vying for influence in oil/gas-rich areas is an emerging dynamic – one which can still be prevented using economic and political tools. Although the energy sector has partially resumed activities since 2016, Shabwa is now the epicentre of a looming dispute over oil production, transit and export control. In Yemen, the location of oil/gas fields and energy infrastructures reflect the lack of an agreed power centre and the rise of militiadoms. Yemen’s oilfields are mainly located in areas still held by pro-government forces: the northern and eastern parts of the governorate of Marib, the hinterland of the province of Shabwa and the northern part of Hadramawt (Wadi Hadramawt, Masila Basin). Conversely, export terminals and ports are in territories controlled predominantly by the Houthis (e.g. the Red Sea oil terminals at Ras Isa; Hodeida port), or with a strong presence of pro-STC secessionist groups (Aden; the coastal region of Shabwa; and Hadramawt). In 2015-16, AQAP seized the oil terminal of Ash Shihr (Hadramawt). Currently, the authorities are not able to use Yemen’s main oil export pipeline, the Marib-Ras Isa, which crosses Houthi-held areas; a shorter pipeline links the Masila oilfields with the Ash Shihr export terminal. In 2019, the government started to build new segments of a pipeline connecting the Marib and Shabwa oilfields with the Bir Ali oil terminal (Shabwa), thus bypassing the lands controlled by the Houthis. Yemen’s only gas pipeline links the Marib-Al Jawf gasfield with the LNG export plant in Balhaf (Shabwa).

Oil politics has usually mirrored Yemeni power balances.

The presence in oil/gas-rich areas of militiadoms, who are backed by foreign state powers, increases the risk of clashes over resources: moreover, ideological factors are clearly at play. Pro-government and Saudi-backed forces in oil-rich territories are mostly tied to the Islah party and the Muslim Brotherhood (financed also by Qatar and towards whom Turkey has made overtures); in contrast, Emirati-supported groups who are stronger in littoral areas have secessionist goals and Salafi beliefs. Oil politics has usually mirrored Yemeni power balances: the prominent Al Ahmar family and also General Ali Mohsen Al Ahmar (no relation), both close to the Islah party, have economic interests in the oil sector and the General’s military forces now have the upper hand in oilfield areas. In August 2019, southern secessionists temporarily gained military advantage in Shabwa vis-à-vis pro-Hadi forces. The Riyadh Agreement, the Saudi-brokered power-sharing deal signed in November 2019 between the internationally-recognised government and the STC, should help contain clashes: but the agreement appeared to be in jeopardy following the renewed outbreak of fighting in Shabwa in January 2020. The Houthis are also advancing militarily in Al Jawf and the oil/gas-rich Marib governorate.

Linking development and security in a decentralised Yemen

Given the degree of political-military fragmentation and the high number of interlocutors, conflict resolution efforts in Yemen have produced very limited results so far. Patchwork agreements focused on local ceasefires and confidence-building measures (e.g. the Hodeida Agreement and the Riyadh Agreement) can contribute to reducing large-scale violence, but they lack an overarching national dimension. The Riyadh Agreement, for example, does not address the southern separatists’ demands for autonomy. Therefore, auxiliary security forces loyal to the STC could easily derail power-sharing institutions if their demands for local autonomy are not met. Indeed, the multiplicity of security forces and providers makes implementation of peace agreements generally difficult, with several potential spoilers to the frameworks. Pro-government militias increase the risk of conflict recurrence as they are often left out of peace negotiations and have little incentives to respect the deals that have been reached.8 In Yemen, this could be the case of the West Coast Forces led by Tariq Saleh (nephew of the former president), excluded by the Riyadh Agreement and with fluid external allegiances.

Yemen needs to start anew on the basis of local agency and ownership, investing in local councils and regionally-tailored security forces to rebuild national state institutions.9 In so doing, any security sector reform (SSR) plan has to deal with the Yemeni reality of multiple security providers to be effective: therefore, it cannot be designed starting from a state-centric approach to security reform.10 For this purpose, the EU and international actors could focus on the flexibility in alignments and alliance-making (the ´never is forever` approach rooted in tribal mediation)11 that is a traditional characteristic of Yemeni politics, supporting a political initiative for reform leading to a federal system of governance, based on the principles agreed upon in the Outcome Document of the Comprehensive National Dialogue Conference (2013-14).

‘Bottom-up’ federalism has emerged as a de facto reality in conflict-torn Yemen: the war has reconfigured Yemeni economic relations, giving a greater role to territorial players. For instance, the internationally recognised government pays the Hadramawt Tribal Confederation and the Petro Masila state company - which runs the oilfields in Wadi Hadramawt - to access the sites: in Mukalla, the recognised government pays local authorities and the Hadrami Elite Forces (in cash or fuel) for access to the oil facilities.12 As an emerging dynamic, confrontation in oil/gas-rich areas can still be contained by focusing on economic decentralisation and inclusive development. A more equitable distribution of oil and gas revenues must be part of a federal scheme to prevent new centre-periphery tensions and instead improve services for local communities. In the oil-rich regions of Marib and Hadramawt, governors have started to retain 20% of energy revenues at local level for development programmes, in coordination with the recognised government. The link between economic decentralisation and local security would strengthen Yemen’s federal architecture: it would also bind tribal chiefs’ loyalty on the ground, helping them to (re)acquire authority vis-à-vis tribal fighters. The EU can stress the value of this decentralised approach to better complement the United Nations’ diplomatic efforts towards a nationwide ceasefire: this could be pursued by promoting inter-Yemeni talks on federal reform and mechanisms to operationalise local security and development.

Establishing a Yemeni National Guard (YNG)13 as a complementary, regionally-oriented and tailored force distinct from the army, would diminish the power of militiadoms, and allow for Yemen’s multiple security governance to be brought under the umbrella of a Yemeni-owned political process. Technically part of the ministry of defence, like a gendarmerie-type force, the YNG would be under the command of the central government in the event of national emergencies (e.g. armed insurgency against central institutions, aggressive interventions by external powers, or natural disasters). The reconstruction of the army should be pursued in parallel with the creation of a YNG to overcome rivalries over financial resources, key positions and external funding. The advantage presented by the YNG in terms of the Yemeni federal state framework is that it would build on close ties and interaction with the population (something that cannot be achieved by the army’s system of rotating units), addressing broader security matters from a local and community-centred perspective. Training for the YNG would focus on regionally-targeted issues: border security and anti-smuggling activities (e.g. Hajja, Saada, Mahra), counter-terrorism (e.g. Abyan, Al-Bayda, Hadramawt), protection of energy and/or logistical infrastructures (e.g. Marib, Shabwa, Hadramawt, Hodeida), and demining (Hodeida, Taiz). The EU could play a role as training coordinator of the YNG, working as part of a multinational team of military experts.

At the budgetary level, each governorate would partially contribute to its own security, co-financing its division of the YNG through the reinvestment of a variable share of the regional budget (local taxes, fees and energy revenues). The largest share would be covered by external donors through central institutions, under international monitoring, especially for less wealthy regions. This would help keep the wealth in local hands, thus incentivising members of militias or state-sponsored armed groups to engage part-time in the regular security sector, while still performing a civilian job. Regional commanders of the YNG would be appointed by governors in consultation with local councils; reintegration of single combatants, rather than of pre-existing armed groups as such, should facilitate loyalty and cohesion. Governorates’ budgets would co-finance the YNG in an endeavour to generate local security, thus creating a conducive environment for development.

Finally, the promotion of effective powers at a local level ought to be accompanied by the rebuilding of a national political framework. Unified and strong institutions are essential to handle decentralisation:14 Yemeni stakeholders must agree, before engaging in SSR, on a single centre of power, within a federal institutional architecture. This would bridge the centre-periphery divide, unlike the 2014 six-regions federal reform approved by the presidential committee (and not implemented), which was rejected by many Yemeni actors. Militiadoms result from the fragmentation and triplication of the Yemeni institutional framework. Transnational patronage by Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Iran has facilitated the survival and consolidation of these armed groups. Formalising this federalism ´from below` should contribute not only to establish a viable national framework again, but also to reduce the space for external interference in Yemen. By investing in this decentralised approach, the EU and the UN can design a complementary path towards stabilisation.

Conclusion

Yemen’s conflict is complex and multi-layered. An analysis that focuses on the ‘proxy dimension’ of the war is not sufficient to understand its drivers and implications, nor to devise viable solutions for post-conflict governance. The presence of rival regional powers vying for control and influence on the territory has led to a paradigm shift from hybrid to multiple security governance, given the lack of a single state entity and the presence of various militiadoms competing against one another. Although Yemen’s militiadoms maintain a degree of operative autonomy, foreign state powers have managed to capitalise on the political fragmentation that has bedevilled the country thanks also to transnational patronage networks.

This local-foreign nexus has reshaped Yemeni politics, contributing to the worsening of overall human security, which the current pandemic crisis threatens to further aggravate. The first case of Covid-19 was identified in Yemen on 10 April: shortly afterwards, Saudi Arabia declared a unilateral truce. The United Nations are working to build an inter-Yemeni consensus to reach a nationwide ceasefire. But the Houthis are in a position of force militarily and politically. Moreover, as the response to the pandemic is uncoordinated among the official government, the self-proclaimed Houthi government and the local authorities, a potential health crisis is likely to increase political fragmentation and, as a result, the role of militiadoms.

In the hope that this troubled scenario can be overcome, restarting from local agency would formalise Yemen’s de facto federal reality, but in a national scheme agreeing on a single power centre. In this framework, the proposed YNG would be an invaluable asset to build a decentralised state linking bottom-up development to security.

References

1) For a background on Yemen’s history and the regime of Ali Abdullah Saleh, see Sarah Phillips, Yemen’s Democracy Experiment in Regional Perspective (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). On the north and the Houthis, see Marieke Brandt, Tribes and Politics in Yemen. A History of the Houthi Conflict (London: Hurst & Co, 2017). On the southern secessionist issue, see Peter Salisbury, “Yemen’s Southern Powder Keg”, Research Paper, Chatham House, March 2018 https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/yemens-southern-powder-keg.

2) For more on the concept of ‘militiadoms’, see Eleonora Ardemagni, “Yemen’s nested conflict(s): Layers, geographies and feuds”, ORIENT-German Journal for Politics, Economics and Culture of the Middle East, no. 2, April 2019, pp. 35-41. See also Philip S. Khoury and Joseph Kostiner (eds.), Tribes and State Formation in the Middle East (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991). Investigating pre-State political formations, Khoury and Kostiner stress the concept of chiefdom (or chieftancy) to indicate an ‘intermediate political formation between tribes and states.’

3) Antonio Giustozzi, “The Debate on Warlordism: The Importance of Military Legitimacy”, Crisis States Research Centre, Development Studies Institute (DESTIN), London School of Economics and Political Science, Discussion Paper no. 13, October 2005, p. 15, http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/13316/.

4) Eleonora Ardemagni, “Yemen’s Military: From the Tribal Army to the Warlords”, Commentary, in Trapped in War: Yemen, Three Years On, ISPI Dossier, Italian Institute for International Political Studies, March 20, 2018, https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/yemens-military-tribal-army-…; Eleonora Ardemagni, “Patchwork Security: The New Face of Yemen’s Hybridity”, Commentary, in Eleonora Ardemagni and Yezid Sayigh (eds.), Hybridizing Security: Armies and Militias in Fractured Arab States, ISPI-Carnegie Middle East Center Dossier, October 30, 2018, https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/patchwork-security-new-face-….

5) On Yemen’s post-2015 security providers, see Eleonora Ardemagni, Ahmed Nagi and Mareike Transfeld, “Shuyyukh, Policemen and Supervisors: Yemen’s Competing Security Providers”, ISPI-Carnegie Middle East Center-Yemen Polling Center, Analysis, March 26, 2020, https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/shuyyukh-policemen-and-super….

6) See the point made by Stacey Philbrick Yadav in “Roundtable: Backdrop & Reverberation of Soleimani’s Assassination”, Jadaliyya, January 21, 2020, https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/40546.

7) Thanassis Cambanis et al., Hybrid Actors. Armed Groups and State Fragmentation in the Middle East, The Century Foundation, October 2019, p. 16, https://tcf.org/content/report/hybrid-actors/.

8) Christoph V. Steinert, Janina I. Steinert and Sabine C. Carey, “Spoilers of Peace: Pro-government militias as risk factors for conflict recurrence”, Journal of Peace Research, vol. 56, 2, March 2019, pp. 249-63; United Nations University-Centre for Policy Research, Auxiliaries in Conflict: How militias impact post-conflict peace, stabilization and justice, Research project, 2019-20, https://unu.edu/projects/auxiliaries-in-conflict-how-militias-impact-po….

9) The Local Authorities Law, approved and introduced by the government in 2000, addresses regional claims for greater autonomy (providing for the devolution of power in some limited domains). According to the text, the central government remains in charge of foreign policy and national security laws and can veto local decisions: it also controls energy revenues. Local councils are responsible for everyday political affairs and can collect taxes, and also have decision-making competences on finances and how to apply development programmes.

10) Nadine Ansorg and Eleanor Gordon, “Co-operation, Contestation and Complexity in Post-Conflict Security Sector Reform”, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, vol. 13, no. 1, 2019, pp. 2-24, https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1516392.

11) On tribes and tribal mediation in Yemen, see Nadwa Al Dawsari, “Tribal Governance and Stability in Yemen”, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Paper, April 2012, https://carnegieendowment.org/2012/04/24/tribal-governance-and-stabilit…; François Burgat, “Le réglement des conflits tribaux au Yémen”, in “Le shaykh et le procureur”, Égypte/Monde arabe, troisiéme série, no. 1, 2005, https://journals.openedition.org/ema/1042#xd_co_f=NTYxZDk5YzMtZWE2ZS00O…;

12) Wadhah al-Awlaqi and Maged al-Madaji, “Challenges for Yemen’s Local Governance amid Conflict: Rethinking Yemen’s Economy”, Policy Brief, Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies-DeepRoot Consulting-CARPO Center for Applied Research in Partnership with the Orient, July 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/6314.

13) Eleonora Ardemagni, “Localizing Security: A National Guard for Federal Yemen”, Policy Brief, Italian Institute for International Political Studies (ISPI), December 13, 2018, https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/localizing-security-national….

14) Osamah Al Rawhani, “A Strong Central State: A Prerequisite for Effective Local Governance in Yemen”, Arab Reform Initiative, October 17, 2019, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/a-strong-central-state-a-prereq….