You are here

Appeasement and autonomy

Introduction

Armenia’s foreign policy and its role in the post-Soviet space are often characterised as ‘pro-Russian’. While such a description is partially true, it is overly simplistic. This Brief analysis the main trends and evolutions in Armenia’s Russia policy after the 2018 Velvet Revolution: how the changes have influenced Russia’s approach towards Armenia, how these dynamics affect Armenia’s autonomy and what the consequences of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war are for Armenia’s regional security and alliances.

After the revolution and up until the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, no substantial strategic changes were made to Armenian foreign policy. The leadership has avoided framing its external affairs in geopolitical ‘pro or against’ terms, promoting a ‘pro-Armenian’ policy that aims to maintain good relations in all directions and prioritises sovereignty as a foreign policy principle. Instead, the revolutionary ambitions of the new leadership have been directed towards domestic issues such as fighting corruption, reforming the judiciary and law enforcement bodies, improving the business environment and addressing social issues.

The main determinants of Armenia’s foreign policy are security threats, which lead it to perceive Russia as the only viable security provider.

The main determinants of Armenia’s foreign policy are security threats – the ongoing Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the military threats from Turkey and Azerbaijan, and Armenia’s closed borders in the east and west. These security threats also explain the rationale behind Armenia’s Russia policy, leading it to perceive Russia as the only viable security provider. This has been sealed by extensive bilateral agreements and Armenia’s participation in Russia-led regional projects such as the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) and the Russian-Armenian Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, and the agreement to establish a Russian military base in Armenia, etc. Nevertheless, in the past decade, Russia has also sold weapons to Azerbaijan, albeit at market prices, while Turkey’s military support for Azerbaijan has increased dramatically over the past year, constraining Russia’s ability to prevent conflict. Before this, Russia had been able to maintain the status quo, exercising its strong influence on both sides of the conflict, making it the unofficial primus inter pares co-chair of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group, which is mandated to mediate the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Russia also exerts powerful economic influence over Armenia. Armenia’s overreliance on Russia has come at the cost of ceding the strategic assets of its energy, transport and other infrastructure, hampering its ability to create new trade partnerships and diversify its economic structure, and consequently deepening asymmetry in its relations with Russia, which has created expectations of loyalty in Moscow. After the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and Armenia’s defeat, the country’s dependence on Russia – the deal-broker with Azerbaijan (and Turkey) and the guarantor of Karabakh’s fragile security through its peacekeepers – is only set to increase as the country becomes mired in deep political, security and economic crises.

Mistrust from Moscow - appeasement from Yerevan

Armenia’s overreliance on Russia has resulted in its foreign policy manoeuvring being constrained, with Russia increasingly consolidating its political and economic leverage over the country; however, foreign policy manoeuvring has also been limited because of the interpersonal ties and perceptions of Armenia’s leadership. In 2018, Russia found itself in a curious situation when the regime of Serzh Sargsyan, regarded by Moscow as quite malleable, was toppled by a movement that expressed no anti-Russian agenda.1 When it became increasingly likely that Sargsyan would fall, Russia put its support behind Karen Karapetyan, the then first deputy prime minister and a career Gazprom official. Reflecting this preference, Russian media attempted to discredit the protests against Sargsyan led by Nikol Pashinyan.2 However, when he became acting prime minister, backing the increasingly unpopular Karapetyan at any cost was not in Russia’s interests, as it might have given the protests the geopolitical agenda they had so far lacked. Considering the scale and popularity of the protest movement, Russia’s stance could have irreversibly harmed its public image in Armenia. Thus, democratic legitimacy became a pillar of Armenia’s post-revolutionary foreign policy, increasing the country’s sovereignty vis-à-vis external actors.

At least until June 2020, the Armenian government, led by Pashinyan since May 2018, still enjoyed overwhelmingly high levels of public support.3 During this period, attempts were made by Russian economic-political actors (often from the Armenian diaspora) to back anti-government groups and former ruling parties, with the possible aim of only testing the government’s resilience. Pashinyan was forced to prove his pro-Russian credentials, also giving in to domestic pressures, as the opportunistic opposition players tried to win Moscow’s sympathy by presenting the revolutionaries as the ‘anti-Russian puppets of Soros’.4 If Russia had actively supported such groups, which were extremely unpopular, or explicitly pressurised the government, it would have further diminished its image in the eyes of Armenians as the main friend of the country. According to a poll conducted in 2019, only 57% of respondents considered that Russia is the main friend of Armenia, down from 83% in 2013, and, in addition, the demand for greater self-reliance has been growing.5 Relying on his legitimacy and overestimating the extent to which the revolutionary elites are acceptable to Moscow, Nikol Pashinyan tried to pursue a more independent policy towards Russia, overconfident that the Kremlin would tolerate his government’s ambition of greater autonomy because of his popularity and the lack of any prospect of regime change prior to the 2020 war.

Paradoxically, the desire to boost Armenia’s autonomy has forced Pashinyan into a policy of appeasement towards Russia.

Unfortunately, the Armenian leadership has failed to use this leverage and its legitimacy to boost Armenia’s practical autonomy vis-à-vis Russia, instead wasting this resource for largely symbolic gains. Domestically, the most defiant of these moves was pursuing former pro-Russian president and friend of Putin Robert Kocharyan and the Secretary-General of the CSTO Yuri Khachaturov and pressing charges over the violent suppression of the 2008 post-election protests.6 Robert Kocharyan’s detention7 was perceived as a politically, perhaps even geopolitically, motivated event in the Russian media.8 Khachaturov’s recall from his post and the filing of criminal charges had an exclusively domestic focus, but Moscow interpreted the move as damaging to CSTO’s institutional reputation and against the spirit of allied relations.9

Furthermore, in 2018, the Armenian government cancelled plans to transfer the state-owned High Voltage Electric Networks of Armenia under the discretionary management of the Russian Tashir Group, headed by a diaspora businessman. Soon after this, the authorities did not rush to intervene when a group of protestors disrupted the operations of GeoProMining, a Russian mining giant,10 while Armenian law enforcement bodies began investigations into South Caucasus Railways, which is 100% owned by Russian Railways.11 Sergei Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, expressed his discontent over these legal processes and suggested a connection between them, as well as with the price of Russian gas in the country.12 The ongoing negotiations over these trade-offs13 could set the limits for what the Kremlin is willing to tolerate with regard to Armenia’s autonomous actions concerning Russia’s key interests. Meanwhile, Pashinyan has backed his actions with calls for sovereignty, non-interference in domestic affairs and consideration of Armenia’s national interests, which have not been well-received in Moscow.14 However, as the post-war realities force Armenia to negotiate from a much weaker position, in greater need of Russian assistance, the government has toned down its rhetoric.

These moves by the new government could have been interpreted as purely domestic matters; however, they have been interpreted by Moscow in the context of Pashinyan’s statements and stance on Russia before he came to power. Pashinyan had previously criticised the asymmetry in Armenian-Russian relations, questioned the effectiveness of the CSTO, voted against Armenia’s membership of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) as an MP and introduced a bill demanding Armenia’s exit from the bloc.15 Before leading the state, Pashinyan believed that, "by joining the EAEU, Armenia loses its strategic perspectives and motivations, becoming a wretched tenant of the Eurasian economic space", and that joining the Union "is a process of isolation and not of integration".16 In addition, Russia’s mistrust of revolutions in the post-Soviet region only exacerbated Moscow’s misgivings about the new government in Yerevan, especially considering the fact that many among the new political elite had come from civil society organisations, which are often connected to various Western non-governmental organisations.

Because of factors that have instilled more and more scepticism into the Kremlin’s reading of post-revolutionary Armenia and the sincerity of the new government’s dedication to the alliance with Russia, Pashinyan has been compelled to be even more pro-Russian than his predecessors, in order to keep the strategically important alliance alive. Paradoxically, the desire to boost Armenia’s autonomy has forced Pashinyan into a policy of appeasement towards Russia. Given this combination of factors, a move towards more (symbolic) autonomy vis-à-vis Russia triggered the need for acts showing Armenia’s loyalty to the alliance, resulting de facto in less rather than more autonomy. This was seen, for instance, in Yerevan’s decision to send a demining and humanitarian mission to Syria after the revolution in response to calls from Russia, which had earlier been refused by the previous government, as well as by Russia’s other CSTO allies.17

As long as Pashinyan does not present an open risk to Russia’s key areas of interest, Moscow has been willing to work with his government. Under these circumstances, Pashinyan has not sought to – nor is he able to – change the course of Armenia’s Russia policy. Instead, he has aspired to utilise the alliance in defence of Armenia’s interests as much as the existing frameworks have allowed. Pashinyan has tried to steer Armenia’s membership in the Russian-led CSTO and EAEU by revitalising the declared purposes of these organisations. This strategy has been pursued through two main means: (1) increasing the effectiveness of the organisations and (2) strengthening the formalisation and institutionalisation of cooperation within the organisations – increasing their predictability and reliability and fixing the terms of how exactly Armenia can benefit from them. Economically, this strategy has aimed to enhance the benefits received by Armenia, while, in terms of security, attempting to formalise relations within the CSTO by setting clear rules, procedures and expectations to ensure that deterrence will work when needed most.

Hence, instead of pursuing the former policy of ‘bandwagoning’, leading to overreliance on Russia, Pashinyan’s foreign policy with Russia has attempted to lean towards ‘hedging’, which could provide more room to manoeuvre within the existing frameworks. By formalising, institutionalising and giving assurances about its ties (or the alliance) with Moscow and other CSTO members, Yerevan has aimed to offset any risks and maximise its influence. One of the aims of hedging is to increase the flexibility of a country’s foreign policy. Hedging may allow the development of commercial ties and value-based cooperation between Armenia and the EU (or different types of cooperation with other power centres), while demonstrating loyalty to Russian (geo)political interests in the region.18 Although this strategy could potentially strengthen Armenia’s sovereignty, the need to give stronger reassurances to Russia has only further accentuated the policy of appeasement. In other words, hedging was a risky endeavour whose aim was to foster ties with other actors while placating Russia, in line with Yerevan’s long-declared foreign policy principle of ‘complementarity’.

Armenia's economic dependence on Russia

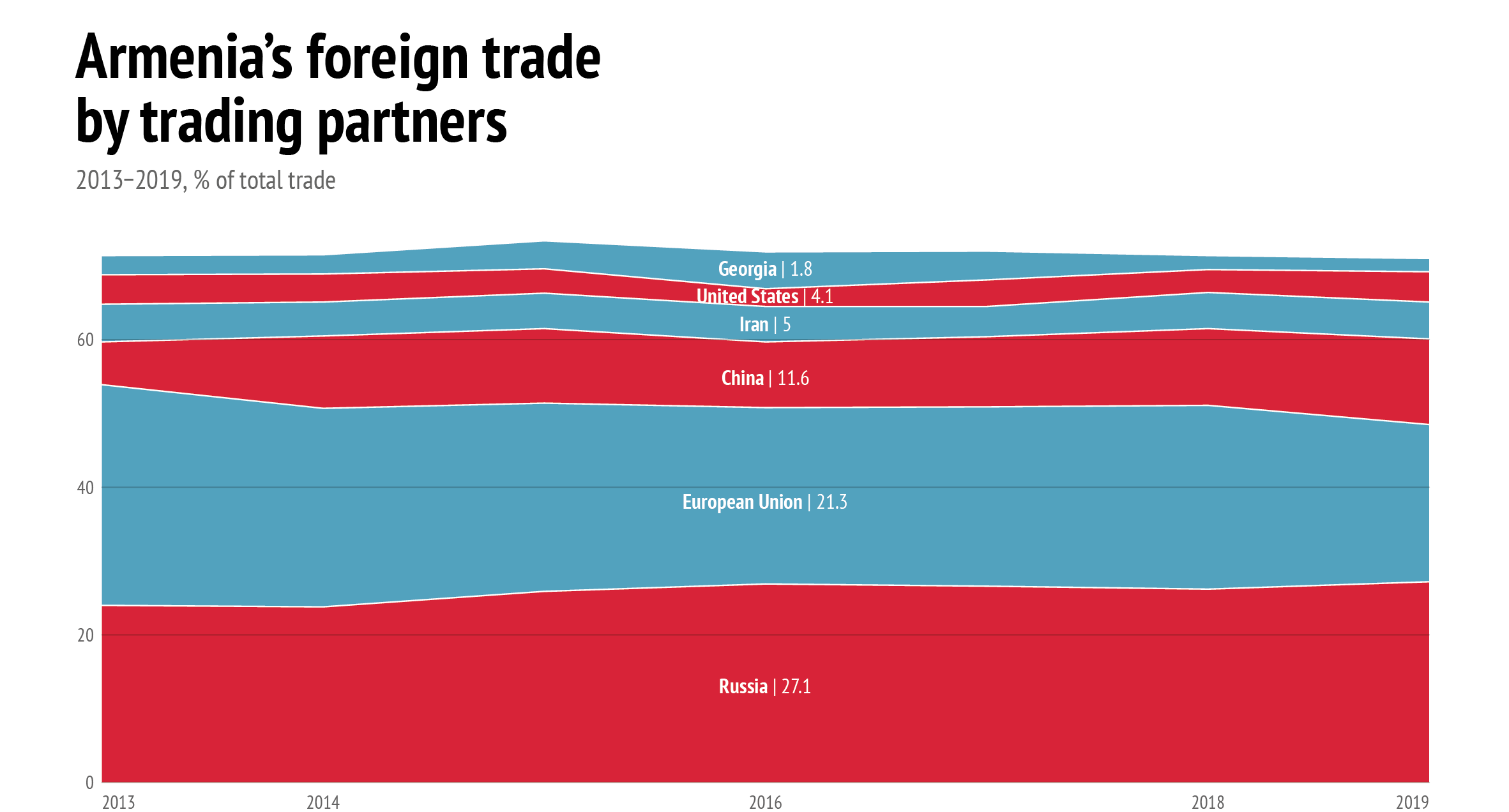

Russia is Armenia’s largest trading partner and investor. The trade turnover with the EAEU (more than 95% of which is with Russia) has over the past few years surpassed the EU-Armenia trade turnover and the gap keeps widening, although in absolute numbers EU-Armenia trade largely keeps growing. As a result, almost one-third of Armenia’s overall foreign trade is with Russia.19 However, when it comes to foreign direct investment, Russia provides half of Armenia’s accumulated stock, with no other partner’s share exceeding 10%.20

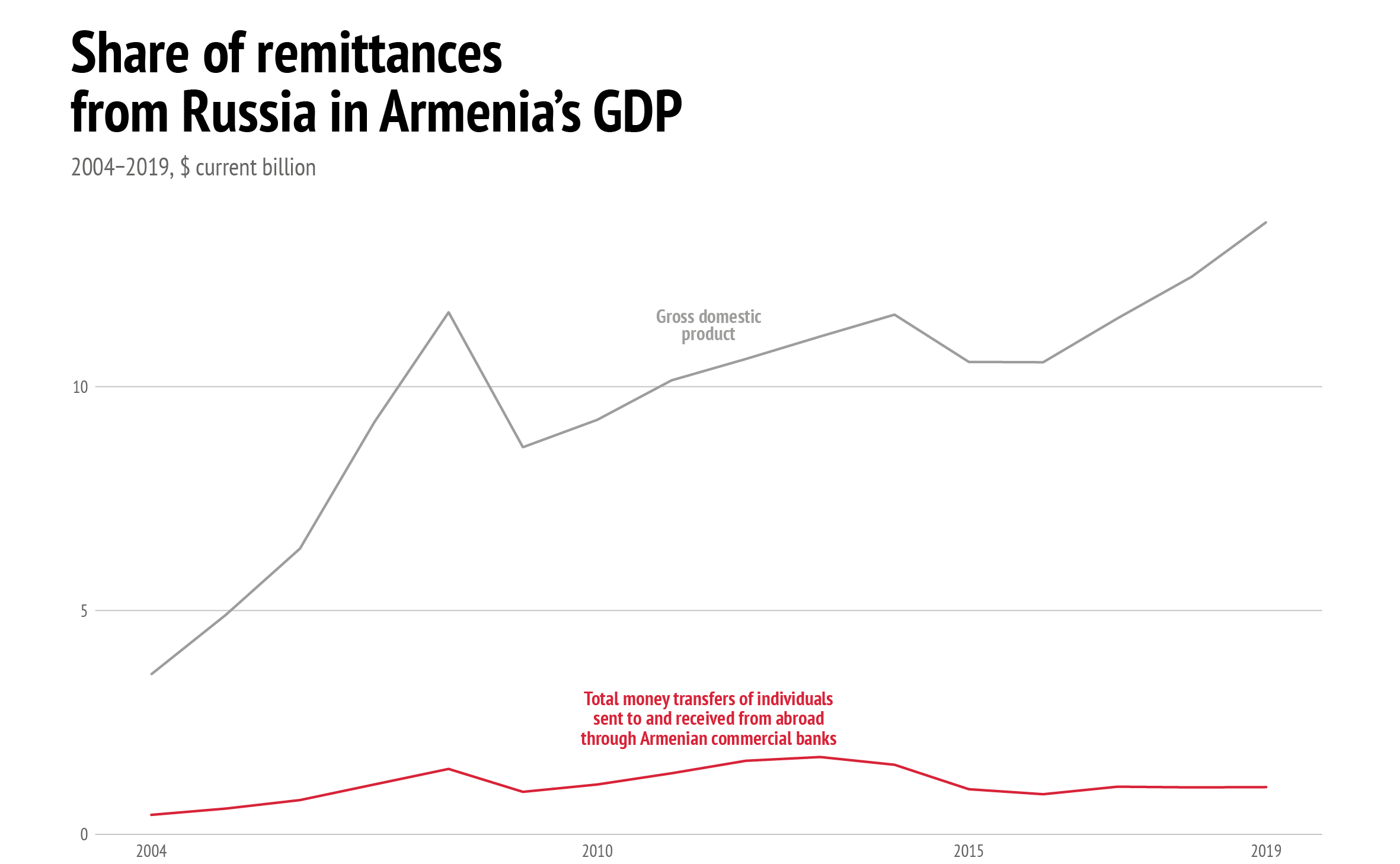

Russia hosts Armenia’s biggest diaspora and is the main destination of labour migrants. The share of remittances from Russia in Armenia’s GDP was 15.5% in 2012. With the decline of the Russian economy since 2014, remittances fell by 45% over two years and made up 7.7% of Armenia’s GDP in 2019.21 Notwithstanding the ongoing weakness of the Russian economy, Armenia needs to generate growth by rebalancing exports in order to avoid a further deterioration of its external balance and to address vulnerabilities connected to shocks in the Russian economy.22 This keeps Armenia’s foreign policy tied to and dependent on the remittances from Russia because if Russia wanted to pressurise Armenia into making a particular policy choice or prevent it from embarking on a particular course, it could theoretically create obstacles for migrant workers, thus depriving Armenia of significant cash inflows.

Russia has a monopolistic position in Armenia’s energy, railway, telecommunications, mining and financial domains. It controls 80% of Armenia’s energy sector.23 It annually supplies 2 billion cubic metres of gas to Armenia and owns Gazprom Armenia, the country’s domestic gas distribution network. Although about half a million cubic metres of gas is supplied from Iran, the gas is transformed into electricity and sent back to Iran.24 In 2016, Armenia and Russia reached an agreement on fixing the gas price at $150 per 1,000 cubic metres until the end of 2018. The subsequent 2019 price increase of 10% is often interpreted as a sign of Moscow’s dissatisfaction with how Yerevan conducts its affairs.25 Furthermore, some Russian-friendly sources have argued that Armenia’s State Revenue Committee investigation of Gazprom Armenia’s financial activity, which identified several violations and abuses, was in fact part of Armenia’s tactics in the negotiations over the gas price.26 Although no final price has been agreed to date, Armenia has tried to join up with Belarus and Kyrgyzstan in an attempt to reduce the price, arguing on the basis of both the price decreases in international markets and the policies of the EAEU, by pushing for a common gas market and the setting of tariffs for transport.27 However, this strategy has its risks: justifying the demand for a price cut by the decrease in prices in international markets may not be the wisest strategy for Armenia, as Russia may offer to trade on the basis of floating prices, which could seriously damage the Armenian economy if international prices increase.

When it comes to the common gas market, which is set to commence in 2025, Russia and Kazakhstan are not eager to relinquish the current mechanisms, which keep control in the hands of suppliers. A recent attempt to settle the price dispute failed and Vladimir Putin concluded that a "uniform tariff may be realised only on a single market with a uniform budget and uniform tax system".28 On the one hand, a single market brings lower prices, more regulation and reliability, which are desired by Armenia; however, on the other hand, it means less sovereignty for all members – neither desired by Armenia, nor yet institutionally feasible.29 It is thus unlikely that the EAEU common market will be established according to the envisaged schedule, if indeed at all.

Data: Central Bank of Armenia, 2020; World Bank, 2020

Russia's role after the July 2020 skirmishes

The primary issue that has, over the years, pushed Armenia closer to Russia – the Turkish threat – increased significantly in importance in 2020, with the Armenian-Russian axis failing to react accordingly. The Turkish threat in the region had often been downplayed because Turkey had refrained from explicitly threatening Armenia since the 1990s.

After almost two years of relative calm in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone, July 2020 saw an intensification of fighting, albeit isolated, on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border over one military post. During the escalation, Turkey quickly expressed its full support for the Azerbaijani actions30 and declared itself on that side of the conflict,31 with Azerbaijan threatening to shell Armenia’s nuclear power plant.32 Over the four days of clashes, Moscow made more efforts than any other country towards de-escalation through dialogue with Ankara, Baku and Yerevan, and at the diplomatic level addressed the risks concerning Turkish expansionist aspirations in the South Caucasus.33

Turkey redrew the security architecture of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict and shifted the odds in favour of another war.

The growth of Turkish ambitions in the South Caucasus has suggested a shift in its regional policy. By showing a readiness to engage militarily and to offer Azerbaijan a strategic alignment option that it had not had before, Turkey redrew the security architecture of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict and shifted the odds in favour of another war, which had previously been prevented as a result of Russia’s pivotal deterrence policy, which encouraged Azerbaijan to show military caution and pressured Armenia to show loyalty.34 Shifting the military balance in Azerbaijan’s favour, Turkey prepared the ground for a major war two months later.

Data: Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2019

Meanwhile, the July skirmishes resulted in more questions than answers for the Armenian-Russian alliance. Why did Armenia refrain from seeking intervention and would the CSTO have intervened if asked? During the incident, Armenia asked its CSTO ‘allies to demonstrate solidarity and support’,35 without requesting intervention. In response, the CSTO’s reaction was limited to an expression of concern.36 There were several reasons for this. First, the absence of unequivocal backing of Armenia by the CSTO allies was indicative of a lack of shared security concerns and priorities among all members. No one expected Belarusians or Kazakhs, who have closer ties with Azerbaijan, to fight alongside Armenians. Second, the scale of the fighting was rather limited and Russia was able to support Armenia’s military activities by providing intelligence and hardware, without publicising its cooperation. And, finally, it may have been motivated by the belief that cracks in the alliance would cast doubt on the members’ commitment to undertake a common defence action, thus undermining the deterrence function that the CSTO plays in Armenia’s security architecture. It is also silently acknowledged that Russia will intervene only in the case of full-scale military incursions into Armenian territory, not during isolated clashes. It is because of these reservations that Pashinyan sought to clarify the terms and procedures relating to when and how Armenia should expect assistance from its allies within existing mutual defence obligations.37

The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war and its aftermath

On 27 September 2020, Azerbaijan launched an all-out offensive against Armenian forces along the entire line of contact in Nagorno-Karabakh. While in the first days of the war many people expected an escalation of the conflict with limited scope, as in the four-day war in 2016, Turkey’s overwhelming direct support38 for Azerbaijan, including the deployment of around 2,000 mercenaries from Syria to fight against Armenia,39 made it clear that the war had not been launched for limited military gain, but, rather, to enable Azerbaijan to gain total control over Karabakh and, importantly for the regional security system, to enable Turkey to gain an equal regional status to Russia. Moreover, the continuation of the Azerbaijani offensive after three failed truces on 10, 17, and 25 October, backed by each of the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs Russia, France and the US, only demonstrated Turkey’s unwillingness to agree to any deal reached without its consent and recognition of its regional status. As a result, the fighting continued until 10 November, when a ceasefire was announced jointly by the leaders of Armenia, Russia and Azerbaijan;40 this was followed by consultations between Putin and Erdogan and their ministers of foreign affairs, thus effectively sidelining the Minsk Group co-chairs France and the US.

The ceasefire announcement was a confirmation of Armenia’s military defeat. As a result of war and under the terms of the ceasefire, Armenia had lost control over seven regions surrounding Karabakh proper, as well as significant areas inside Karabakh. Combined, these account for 80% of the territory that was under de facto Armenian control prior to the war. A Russian peacekeeping force of 1,960 military personnel has been deployed in the area left under Armenian control to oversee the ceasefire.41 The ceasefire deal not only includes no mention of Karabakh’s status but also envisages the establishment of a corridor through Armenia’s territory linking Azerbaijan to its Nakhichevan exclave, to be overseen by Russian border troops, and agrees to the opening of all regional communication lines. Importantly, a Russian-Turkish ceasefire monitoring centre has been established in the territory of Azerbaijan, while Turkish officers have been deployed there.42

What does the deal mean for the future of Armenian- Russian relations in the post-war reality? Russia, once the unchallenged dominant regional power, has lost its status in the South Caucasus as the grand broker of regional affairs. While previously Russia had enough leverage over both sides to prevent or alleviate hostilities, this time it could not do so without Turkey’s consent, as Turkey successfully provided Azerbaijan with a strategic alternative and substantially reduced Russia’s formerly pivotal deterrent role in the region. Nevertheless, Russia has finally gained a foothold in Karabakh and so avoided the complete loss of Azerbaijan from its zone of influence. While Russia is legally bound to guarantee Armenia’s security via the CSTO, and Putin reiterated Russia’s commitment to do so during the war,43 it is under no obligation to support Armenia in Karabakh. Doing so openly would send Azerbaijan into Turkey’s wide-open embrace. However, allowing Armenia to lose Karabakh would mean losing Armenia as an ally. Therefore, Russia supplied Armenia with weapons during the war, but, as some experts argue, only with enough to prevent complete defeat, in order to be able to subsequently deploy its peacekeepers and exert more influence over Armenia.44 The inception of the war and, moreover, the defeat of Armenia by the Azerbaijani-Turkish alliance, was not in Russia’s regional interests and constitutes a major setback for Russia in the context of the balance between the capabilities of regional powers.

In spite of the strategic loss, Russia has won a long-desired tactical victory by having a direct military say in the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Once a proponent of a non-alignment policy, Azerbaijan must currently host Russian peacekeepers (implying a Russian military base) as well as a Turkish-Russian ceasefire monitoring centre (implying a Turkish military base). The peacekeeping force must leave Karabakh after 5 years if either side is against the prolongation of its mandate. As Turkish influence in the region and over Azerbaijan grows, presence of the Russian troops might not be tolerated in the long term and further concessions – most probably at the cost of Armenia’s key interests – are possible.

Russia, once the unchallenged dominant regional power, has lost its status in the South Caucasus as the grand broker of regional affairs.

The war has resulted in huge human and territorial losses for Armenia, dealt a significant blow to its military potential and given rise to enormous financial costs, all of which have been made worse by the Covid-19 crisis. In the post-war regional security system, Armenia has granted unprecedented leverage to Russia over its most important foreign and security policy issue, Karabakh, thus effectively ceding a significant margin of autonomy. Russia has already stepped in to help address the above-mentioned crises, as well as overcome the humanitarian catastrophe in Karabakh. If it is not financially supported by the West (or other countries), Armenia will have to turn even more to Russia to seek ways to overcome its economic crisis, further deepening the country’s dependence and vulnerability.

Armenia has little to be happy about with regard to the deal that was reached; at the start of the war, Azerbaijan did not have the aim of hosting Russian troops in Karabakh; and Turkey’s regional ambitions are only just coming to the fore. Considering this, the post-war period might prove to be an interlude before the next war, which might be deadlier than previous conflicts, with Armenia beginning from a much worse position, and might consequently result in larger costs for Armenia. More troubling for Armenia, Russia’s military foothold largely has only political significance; its military presence might not be sufficient to effectively deter or repel a future major offensive by Armenia’s two rivals. Consequently, fortification of the Russian military base in Armenia should be expected alongside increased arms trading and/or the free transfer of weapons to Armenia.

In addition, Armenia faces a political crisis domestically, as defeat has resulted in the mobilisation of all of its political forces, which have demanded Pashinyan’s resignation. However, these actors understand Russia’s increased influence in Armenia and have refrained from questioning Russia’s intentions or the legitimacy of the deal it has brokered. Against this domestic backdrop, Pashinyan offers Moscow guarantees in terms of implementing the agreed deal, while the opposition positions itself as the most desirable replacement for the ‘anti-Russian’ Pashinyan. While the appeasement continues, Armenia’s post-defeat survival strategy forces the country to be more dependent on Russia than it has ever been in the past 30 years, regardless of its leadership’s wishes.

References

1. Alexander Markarov and Vahe Davtyan, “Post-Velvet Revolution: Armenia’s Foreign Policy Challenges,” Demokratizatsiya, vol. 26, no. 4 (2018), pp. 531-46.

2.Lucan Ahmad Way, “Why Didn’t Putin Interfere in Armenia’s Velvet Revolution? His Support for Authoritarianism Abroad Has Limits,”Foreign Affairs, May 17, 2018, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articlesarmenia/2018-05-17/why-didnt-putin-interfere-armenias-velvet-revolution.

3. Center for Insights in Survey Research International Republican Institute, “Public Opinion Survey: Residents of Armenia,” Washington, D.C., June 2020, p. 15, https://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/7.14.2020_armenia_survey_on_ covid_19_response.pdf.

4. Armen Grigoryan, “‘Armenia First’: Behind the Rise of Armenia’s Alt-right Scene,” Open Democracy, September 4, 2019, https://www.opendemocracy.net/ en/odr/armenia-first-behind-the-rise-of-armenias-alt-right-scene/.

5.Caucasus Research Resource Center, “Main Friend of the Country,” Caucasus Barometer time-series dataset Armenia, 2019, https://caucasusbarometer.org/ en/cb-am/MAINFRN/.

6. Nikol Pashinyan himself was one of the leaders of these protests, for which he spent two years in prison.

7. Mikael Zolyan, “Inside the Explosive Case against Armenia’s Ex- President,” Carnegie Moscow Center, August 6, 2018, https://carnegie.ru/ commentary/76985.

8. See, for example, “Правосудие или месть: кому выгодно удерживать Кочаряна под стражей” [Justice or revenge: who benefits from keeping Kocharyan under arrest?], REN TV, July 29, 2019, https://ren.tv/news/v- mire/442947-pravosudie-ili-mest-komu-vygodno-uderzhivat-kochariana- pod-strazhei.

9. “Armenia Reassures Russia after Criticism from Lavrov,” OC Media, August 2, 2018, https://oc-media.org/armenia-reassures-russia-after-criticism-from- lavrov/; Joshua Kucera, “Pashinyan-Lukashenko Spat Intensifies, Threatening CSTO Schism,” Eurasianet, November 21, 2018, https://eurasianet.org/ pashinyan-lukashenko-spat-intensifies-threatening-csto-schism.

10.“GeoProMining: Criminal Elements in Armenia Hinder the Activity of Large Russian Investors,” Arminfo, May 24, 2018, https://arminfo.info/full_news. php?id=31880&lang=3.

11. Alexandr Avanesov, “Lack of Awareness of Rank and File of South Caucasus Railway Was the Reason of Protests,” Arminfo, November 15, 2018, https:// arminfo.info/full_news.php?id=36669&lang=3.

12. “Lavrov Hints Gas Price for Armenia Linked to Criminal Case against Rail Firm,” Panarmenian.net, April 21, 2020, http://www.panarmenian.net/eng/ news/280359/Lavrov_hints_gas_price_for_Armenia_linked_to_criminal_ case_against_rail_firm.

13. “Pashinyan Discussed with Putin Legal Processes around Russian Companies Operating in Armenia,” Armenpress, May 16, 2020, https://armenpress.am/eng/ news/1015516.html.

14. Office of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, “Nikol Pashinyan Meets with Vladimir Putin in Moscow,” September 8, 2018, https://www. primeminister.am/en/press-release/item/2018/09/08/Nikol-Pashinyan-met- with-Vladimir-Putin/.

15 Joshua Kucera, “Pashinyan and Putin Hold First Meeting, Pledge to Build Closer Ties,” Eurasianet, May 14, 2018, https://eurasianet.org/pashinyan-and- putin-hold-first-meeting-pledge-to-build-closer-ties.

16. “Հայաստանի համար ԵՏՄ-ն ոչ թե ինտեգրացիոն, այլ մեկուսացման պրոցես է” [“For Armenia the EAEU is not an integration, but an isolation process”], Armtimes.com, December 4, 2014, https://www.armtimes.com/hy/ article/57021.

17. Eduard Abrahamyan, “Understanding Armenia’s Syrian Gamble,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, vol. 15, issue 129 (2018);.

18. Office of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, “ ‘Armenia Is Ready to Do its Utmost to Ensure Access to New Markets’ – PM Attends ‘The Transit Potential of the Eurasian Continent” Conference’ ”, Yerevan, September,30, 2019, https://www.primeminister.am/en/statements-and-messages/ item/2019/09/30/Nikol-Pashinyan-Eurasian-Economic-Forum/.

19. Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia, https://www.armstat. am/file/article/sv_01_18r_411.pdf; https://www.armstat.am/file/article/ sv_01_20r_411.pdf.

20. Statistical Committee of the Republic of Armenia, https://armstat.am/file/ article/sv_02_20a_420.pdf, pp. 101-102.

21.Central Bank of Armenia, https://www.cba.am/Storage/EN/stat_data_ eng/5.%20Money%20transfers%20of%20individuals_eng.xls; World Bank, “GDP (current US$) – Armenia”, World Bank National Accounts Data, and OECD National Accounts Data Files, no date, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=AM&fbclid=IwAR0b0uOnPESorxN37tjPmiuyH3h8c Ko2EeK33KwATHvr4UVWqrSL6rNxpak.

22.World Bank Group, Future Armenia: Connect, Compete, Prosper. A Systematic Country Diagnostic, Report no.124816-AM, November, 2018, http://documents1. worldbank.org/curated/en/716961524493794871/pdf/Armenia-SCD-in-Eng- final-04192018.pdf.

23.Syuzanna Vasilyan, “Swinging on a Pendulum”, Problems of Post-Communism, vol. 64, no. 1 (2017), pp 32-46, https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2016.1163230.

24. Benyamin Poghosyan, “Benyamin Poghosyan: Russian Gas Price for Armenia as the Key Factor in Bilateral Relations,” CCBS, April 20, 2020, https://ccbs.news/ en/article/811/.

25.Joshua Kucera, “Russia Raises Gas Prices for Armenia in the New Year,” Eurasianet, January 3, 2019, https://eurasianet.org/russia-raises-gas-prices- for-armenia-in-the-new-year.

26. Ani Mejlumyan, “Armenian Investigation of Gazprom Again Tests Ties with Russia,” Eurasianet, November 16, 2018, https://eurasianet.org/armenian- investigation-of-gazprom-again-tests-ties-with-russia.

27. Shaimerden Chikanayev, “Will Gas Tariff Become the Dealbreaker for the Eurasian Economic Union?”, Islamic Finance News, July 15, 2020, https://gratanet. com/laravel-filemanager/files/3/v17i28%2018.pdf.

28.“Russian President: Uniform Tariff on Gas Transit in the EAEU Cannot be Applied in the Current Level of Integration,” Aysor, May 19, 2020, https://www. aysor.am/en/news/2020/05/19/putin-tariff/1697832.

29. “Գազի գնի շուրջ բանակցությունները Ռուսաստանի հետ չեն ավարտվել, բնակիչների համար կապույտ վառելիքը չի թանկանա. Փոխվարչապետ” [“Negotiations on Gas Prices with Russia Are Not Over, Blue Fuel Will Not Become More Expensive for the Residents. Deputy Prime Minister”], Azatutyun, May 21, 2020, https://www. azatutyun.am/a/30625678.html.

30. Ayla Jean Yackley, “Caucasus Fighting Pits Russia against Turkey, Straining Shaky Alliance,” Politico, July 20, 2020, https://www.politico.com/ news/2020/07/20/turkey-russia-azerbaijan-armenia-374878; “Russia Urges Turkish Restraint on Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict,” Massis Post, July 23, 2020, https://massispost.com/2020/07/russia-urges-turkish-restraint-on-armenia-azerbaijan-conflict/.

31. “Turkey Declared Party to Karabakh Conflict”, Azatutyun, August, 28, 2020, https://www.azatutyun.am/a/30809327.html.

32. Chris Jewers, “Azerbaijan Threatens to Cause a ‘Nuclear Catastrophe’ by Attacking Power Station in Armenia amid Deadly Border Clashes,” Daily Mail, July 17, 2020, https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8534029/Azerbaijan- threatens-cause-nuclear-catastrophe-attacking-power-station-Armenia.html.

33.“Putin, Erdogan Discuss Situation on Armenian-Azerbaijani Border,” Tass, July 28, 2020, https://tass.com/politics/1182951; “РФ сделает все возможное для снижения напряженности между Арменией и Азербайджаном – МИД” [“RF Will Do Everything Possible to Reduce Tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan – Foreign Ministry”], Tert.am, July 16, 2020, https://www. tert.am/ru/news/2020/07/16/azerbaijan-russia/3346881; Office of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia, “The Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia Presented the Position of Armenia Regarding the Recent Escalation on the Armenian-Azerbaijani Border and the Nagorno-Karabakh Peace Process”, July 23, 2020, https://www.primeminister.am/en/statements-and-messages/ item/2020/07/23/Cabinet-meeting-Speech/.

34.Laurence Broers, Armenia and Azerbaijan: Anatomy of a Rivalry (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), p. 246.

35. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Armenia, “Remarks by the Permanent Representative of Armenia to the CSTO at the Session of CSTO Permanent Council,” Yerevan, Armenia, July 14, 2020, https://www.mfa.am/en/press- releases/2020/07/14/csto_/10367.

36.CSTO, “The CSTO Secretariat Commentary on the Situation on the Armenian- Azerbaijani Border that Arose on July 12, 2020,” Moscow, July 14, 2020, https:// en.odkb-csto.org/news/news_odkb/kommentariy-sekretariata-odkb-o- situatsii-na-armyano-azerbaydzhanskoy-granitse-voznikshey-12-iyulya-/.

37.“There Are More Serious Issues in CSTO and Issue of Secretary General Is an Occasion to Discuss Them, Says Armenia’s Pashinyan,” Armenpress, November 20, 2018, https://armenpress.am/eng/news/955155.html.

38.Yelena Chernenko, “Принуждение к конфликту” [“Forcing conflict”], Kommerstant, October 16, 2020, https://www.kommersant.ru/ doc/4537733#id1962785.

39. Ron Synovitz, “Are Syrian Mercenaries Helping Azerbaijan Fight for Nagorno-Karabakh?”, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, October 15, 2020, https:// www.rferl.org/a/are-syrian-mercenaries-helping-azerbaijan-fight-for- nagorno-karabakh-/30895331.html.

40. Presidential Executive Office, “Statement by President of the Republic of Azerbaijan, Prime Minister of the Republic of Armenia and President of the Russian Federation”, November 10, 2020, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/ news/64384.

41.Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation, “Обстановка района проведения миротворческой операции (по состоянию на 22 ноября 2020г)” [“Situation in the Area of the Peacekeeping Operation (as of November 22, 2020)”], November 2020, http://mil.ru/russian_peacekeeping_forces/ infograf.htm.

42. Suzan Fraser, “Turkish Parliament Approves Peacekeepers for Azerbaijan,” AP News, November 18, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/turkey-russia-recep- tayyip-erdogan-azerbaijan-armenia-3cc35a16dd70fba816347e95f1072a2d.

43. “Putin Says Russia Remains Committed to All its Obligations to Armenia within CSTO,” Armenpress, October 7, 2020, https://armenpress.am/eng/ news/1030685/.

44.Benyamin Poghosyan, “Nagorno-Karabakh Becomes Russia’s Latest Protectorate in the South Caucasus,” Commonspace.eu, November 19, 2020, https://www.commonspace.eu/opinion/nagorno-karabakh-becomes-russias- latest-protectorate-south-caucasus?fbclid=IwAR01l5H7DUFN0hTqNelRblX yq_N7zBYN154hUpgnlSsIspvO9k7tr3ToWkA.