Summary

- The EU-India relationship is increasingly shaped by shared external pressures but constrained by differing threat perceptions and priorities. This asymmetry is structural, not temporary, and defines the environment in which the partnership must operate.

- Defence and technology illustrate where cooperation is most viable – not through alignment, but through practical, domain-specific collaboration rooted in shared vulnerabilities and risks.

- Trade, including the FTA, remains important, but it can no longer serve as the partnership’s organising centre. The relationship is already evolving towards a more modular partnership built around specific sectors and capabilities.

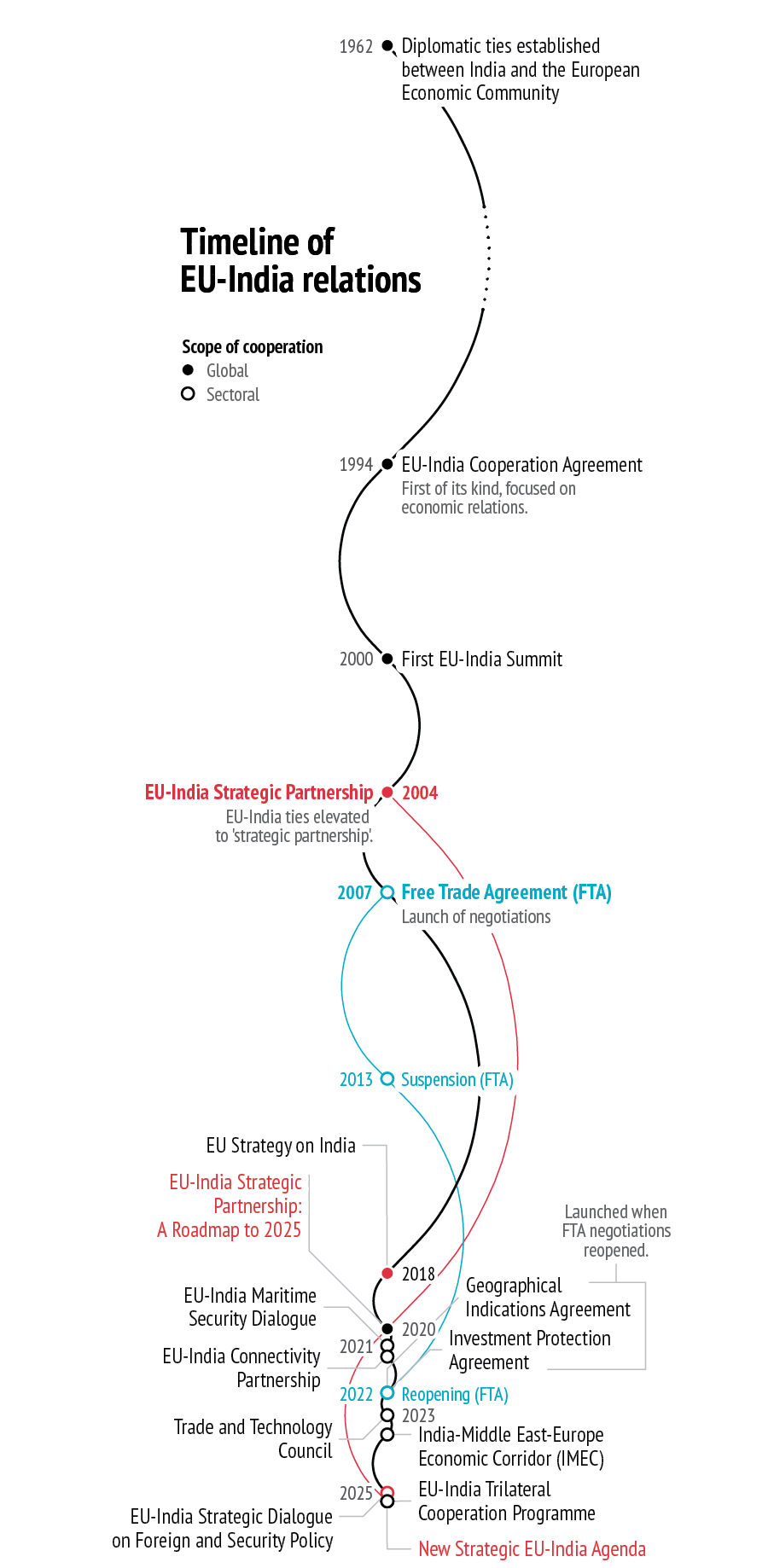

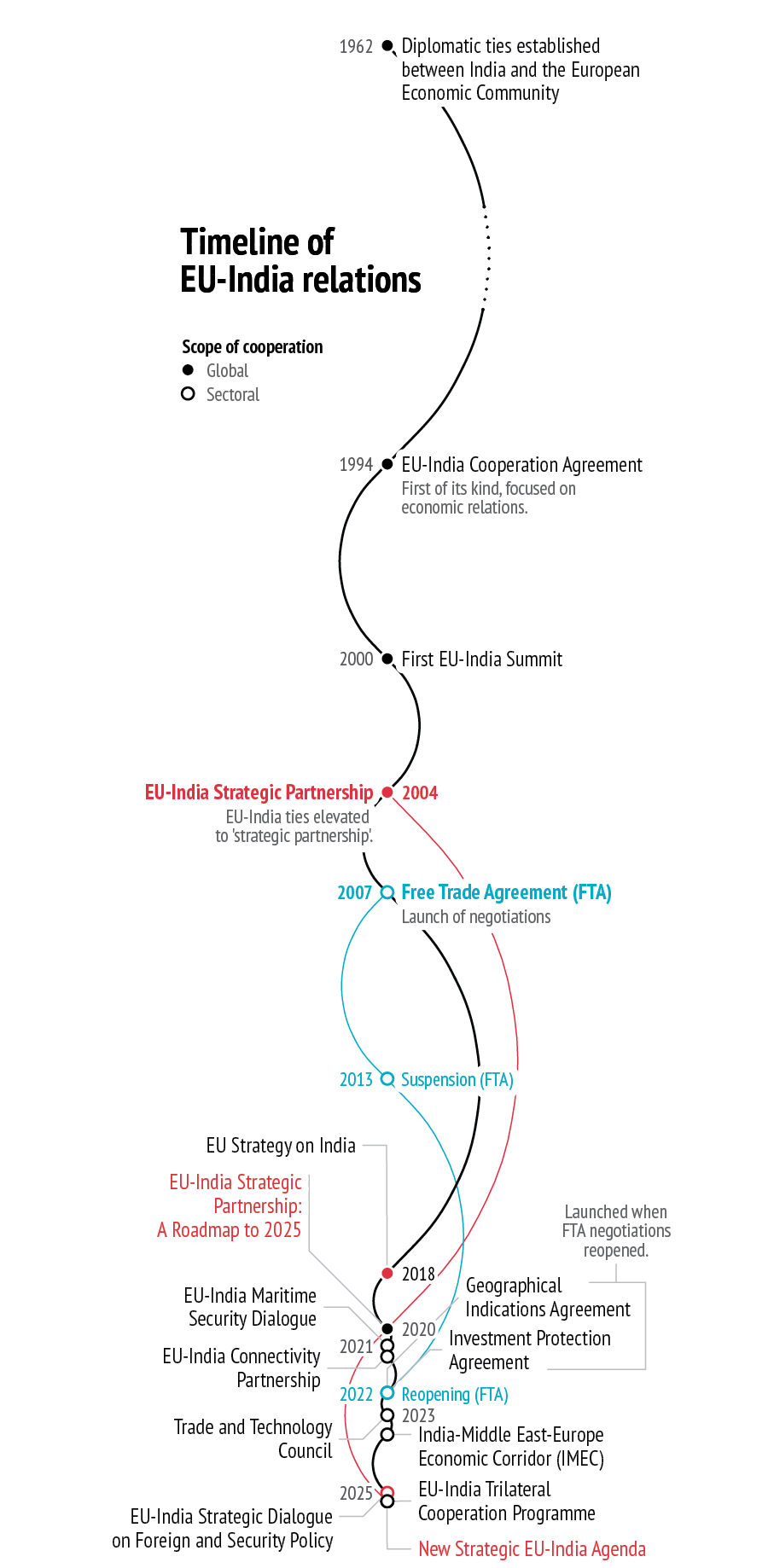

Nearly two decades after negotiations towards a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) began, the EU and India are preparing to finalise a deal that will almost certainly be presented as a watershed moment. Whatever the final text contains, reaching an agreement after years of fits and starts reflects long-haul political investment and a shared recognition of the relationship’s importance. Yet the significance of this moment lies less in the agreement itself than in the global context in which it is being signed.

For much of the past two decades, EU-India relations matured within a relatively stable global environment. India’s relationship with the US functioned as its gold-standard partnership. Europe’s transatlantic bond helped anchor its global posture. That architecture helped absorb differences, allowing both sides to treat their own partnership as a matter of long-term potential rather than immediate necessity. Over time, this latitude fostered a relationship that now accounts for roughly €120 billion(1) in bilateral trade.

That world has changed. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has forced Europe to commit to long-term defence rearmament and deterrence planning. The return of Donald Trump to the White House has reduced trust and introduced uncertainty into Washington’s role for both Brussels and New Delhi, albeit in different ways. Both are widening their partnership portfolios in response to shared pressures, but not from the same starting point. For India, Viksit Bharat, the ambition to become a developed nation by 2047, serves as the overarching framework guiding foreign policy and anchoring strategic autonomy as an operating logic. For Europe, the organising logic has become security-focused. Since 2022, Russia has morphed from a challenging neighbour into an existential threat, reshaping defence priorities, economic policy, energy choices and external engagement.

These are not variations of the same theme. They are different themes. As long as China and Russia define the immediate security environments of India and Europe respectively, this asymmetry will be structural rather than temporary. And this implies that the EU-India partnership cannot be built on expectations of alignment, or on any single organising bargain. It will have to be engineered to function under persistent misalignment, through distinct and purpose-built forms of cooperation.

Structural misalignment

The EU-India relationship is sometimes framed as a natural strategic alignment rooted in shared values and converging interests. It is better understood as a parallel response to a shared pressure environment where interdependence is increasingly weaponised and the international rules-based system is fraying.

The US now sits inside this geopolitical frame. President Trump’s second term has injected uncertainty, and at times open friction, into Washington’s role as a stable partner. The White House’s latest National Security Strategy(2) reflects an increasingly ambiguous posture towards Europe. Similarly, the public deterioration in US-India ties, including tariffs raised to 50%(3) (in part as retaliation for India’s continued imports of Russian oil) has reinforced New Delhi’s instinct to diversify rather than over-commit. Yet even where these pressures might be expected to draw Brussels and New Delhi closer, the Russia-China factor continues to pull them apart.

For Europe, Russia’s war against Ukraine has recalibrated threat perceptions and blurred the line between economic and security policy. This is pushing the EU to secure some €800 billion(4) in defence-related spending and redefining how Europe evaluates its partnerships. India’s decision to preserve ties with Moscow, refrain from political condemnation, and expand economic engagement, particularly via a sharp rise in energy imports(5), has become one of the most persistent sources of friction in the EU-India relationship.

This reflects the fact that India inhabits a different strategic landscape. China, not Russia, is the pacing threat: border conflicts, Beijing’s Belt and Road footprint, maritime encroachment, technological dependence and the deep Sino-Pakistani partnership structure New Delhi’s security outlook. In this environment, Russia remains both a legacy constraint and a managed variable. India is still heavily dependent on Russian-origin platforms (often estimated at around 60%(6)), while simultaneously trying to diversify and indigenise. This is not sentimental alignment. It is a calculated attempt to hedge against the consolidation of a Sino-Russian axis in India’s immediate neighbourhood.

This is the reality in which the EU-India partnership operates, meaning the relationship is shaped less by a common reading of the world than by the need to operate within the same contested environment. That distinction structures its limits, defining what can be coordinated, what must be compartmentalised, and where convergence is unlikely.

Functional convergence

If geopolitics exposes the limits of EU-India convergence, defence and technology reveal where the relationship’s capacity for adaptation is most visible. These are highly sensitive portfolios and irritants remain, yet cooperation is advancing because it is being structured to function in ways that manage Russia-related frictions, institutional asymmetry, and uneven trust.

The central driver is China. For both New Delhi and Brussels, Beijing’s rise is reshaping their security calculus and translating into tangible vulnerability across sectors. Europe’s exposure is now structural, spanning rare earths, clean technologies and advanced manufacturing inputs(7). India’s is embedded across electronics, industrial components and digital ecosystems, with Chinese production networks deeply woven into its economy. In industrial products alone, China accounts for nearly 40% of India’s electronics and telecommunications imports(8). The result is not a shared China strategy, but converging incentives to reduce sensitive dependencies.

This is most visible in domains such as maritime domain awareness, where civilian and military boundaries are increasingly blurred and commercial shipping data, satellite feeds and port information have become central to naval operations, undersea awareness, and grey-zone monitoring. This is where the centre of gravity has shifted from political alignment to operational cooperation, highlighting areas where the EU can act more coherently, for example through initiatives like SHARE.IT, an interoperability framework for maritime situational awareness.

At the same time, the limits of a unified European defence cooperation portfolio are fully apparent. The deepest industrial and strategic ties remain bilateral, most notably with France, with whom India has long-standing political arrangements(9) deepening collaboration in defence research and development, but also with Germany, Poland, and others(10). At EU level, export controls, licensing regimes, and intra-European industrial competition complicate the emergence of a seamless framework. Rather than imposing coherence, the solution has been to work around its absence: depth with some partners, thinner engagement with others, and EU-level cooperation where the tool fits.

What matters is not that this architecture is imperfect, but that it is explicit. Defence and technology cooperation are being built eyes-open, within structural constraints. Trust is developing through projects, interoperability, and co-development, not through political declarations. This is trust as practice. And it shows what the EU-India relationship is becoming: modular, domain-specific, and capable of functioning without full alignment.

The legacy challenge

If defence and technology show where the relationship is adapting, trade shows where it is still catching up. The long arc of FTA negotiations reflects not indifference, but faith that a comprehensive agreement could eventually anchor a strategic partnership.

That belief now sits uneasily with the environment in which the relationship operates. The world that produced many of the EU’s major trade agreements was one of expanding globalisation and relatively stable rules. The world that the EU and India are now navigating is one of retreating openness and regulatory and normative competition. Trade is no longer a domain apart. It is one of the main theatres of competition.

India enters this environment with a development-first logic that does not map cleanly onto Europe’s regulatory approach. New Delhi’s economic strategy is not simply about growth, but upgrading. Initiatives such as ‘Make in India’ – the government’s flagship manufacturing programme – and production-linked incentives are not negotiating positions. They are sovereignty tools. The EU, by contrast, continues to approach economic partnership primarily through rules, standards and comprehensive frameworks. European policymakers often treat the FTA as the natural centre of gravity. Indian policymakers treat it as one instrument among many.

Climate and mobility surface here not as parallel agendas, but as pressure points that expose the limits of the inherited model. Measures such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) are framed in Brussels as climate and industrial policy; in Delhi they are experienced as brakes on long-term development. On mobility, the economic logic of services, skills, and demographic complementarity collides with domestic political constraints on both sides – ranging from EU labour-market politics and migration sensitivities to India’s concerns over skills retention and recognition.

What is increasingly clear is that the problem is not a lack of ambition but the persistence of an inherited approach. The comprehensive trade deal remains the dominant symbol of success, even as much of the relationship is already developing through more sectoral channels. These tracks do not replace trade, but they are increasingly conditioning how the economic relationship functions.

Conclusion

To mature in the new strategic environment, the EU-India relationship must move away from a single organising centre and towards a more modular partnership.

First, geopolitics has to be treated as a management problem, not a convergence exercise. Divergent threat perceptions, especially regarding Russia and China, are structural. The partnership needs a standing strategic track focused not on alignment, but on translating differences into workable cooperation. This requires regularised senior dialogue, signalling channels, and crisis consultation mechanisms that allow disagreement to be identified before it becomes disruptive. Minilateral formats belong naturally here. They allow the partnership to extend into functional coalitions where threat perceptions overlap more closely, without forcing the EU-India relationship itself to become load-bearing.

Second, defence and technology should be formalised as operational corridors. This is already the most functional part of the relationship, precisely because it is domain-specific and practice-driven. Maritime awareness, space security, cyber resilience and undersea capabilities lend themselves to modular cooperation. Some of this will sit more naturally at EU level; other elements will remain anchored in Member State relationships.

Third, the economic relationship needs to be built around economic-security domains rather than a single grand bargain. Trade will remain important. But the centre of gravity is already shifting towards critical minerals, clean technologies, semiconductors, digital ecosystems and resilient supply chains. A modular partnership would treat these as standing pillars of cooperation in their own right, supported by targeted investment, regulatory coordination and industrial collaboration, with the FTA repositioned as one instrument among several rather than the organsing centre.

Across all three anchors, the same logic applies. Coherence emerges not from denying misalignment, but from engineering the partnership to function where interests overlap and to remain viable where they do not. This is the litmus test for how the partnership will be evaluated in the future.

References

1. EEAS, ‘Factsheet: EU-India relations’, 18 September 2025.

2. The White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America, November 2025.

3. The White House, ‘Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump addresses threats to the United States by the Government of the Russian Federation’, 6 August 2025.

4. European Commission, White Paper for European Defence: Readiness 2030, March 2025.

5. Sahai, V., ‘The impact of U.S. sanctions and tariffs on India’s Russian oil imports’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 20 November 2025.

6. Banerjee, V. and Dolbaia, T., ‘Guns, oil, and dependence: Can the Russo-Indian partnership be torpedoed?’, War on the Rocks, 23 September 2025.

7. European Parliamentary Research Service, ‘China’s rare-earth export restrictions’, November 2025.

8. Global Trade Research Initiative, An Examination of India’s Growing Industrial Sector Imports from China, 29 April 2024.

9. Press Information Bureau (India), Ministry of Defence, ‘DRDO and DGA, France ink Technical Agreement to deepen collaboration in defence R&D’, 20 November 2025.

10. News On Air (Prasar Bharati), ‘India and Germany deepen strategic partnership with wide-ranging agreements across defence, trade and technology’, 12 January 2026; Republic of Poland, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ‘India: Bilateral relations’.