Summary

- The Sahel remains key to European security due to interlinked threats – terrorism and its spillover into neighbouring countries, and organised crime networks controlling lucrative drug and human trafficking routes to Europe. Heightened international competition for influence and access to the region’s mineral wealth should also caution the EU against complete disengagement.

- Anti-Western sentiment and strategic hedging have led to the diversification of partnerships under the banner of ‘multipolarity’. But external actors interpret multipolarity according to their respective agendas, while leaders of the Alliance of the Sahelian States (AES) prioritise sovereignty and multi-alignment.

- The EU should respond by pursuing targeted, interest-based cooperation on energy and mining, alongside efforts to counter transnational terrorism and organised crime. It should also engage more selectively in key civilian domains, prioritising education and cooperation with civil society.

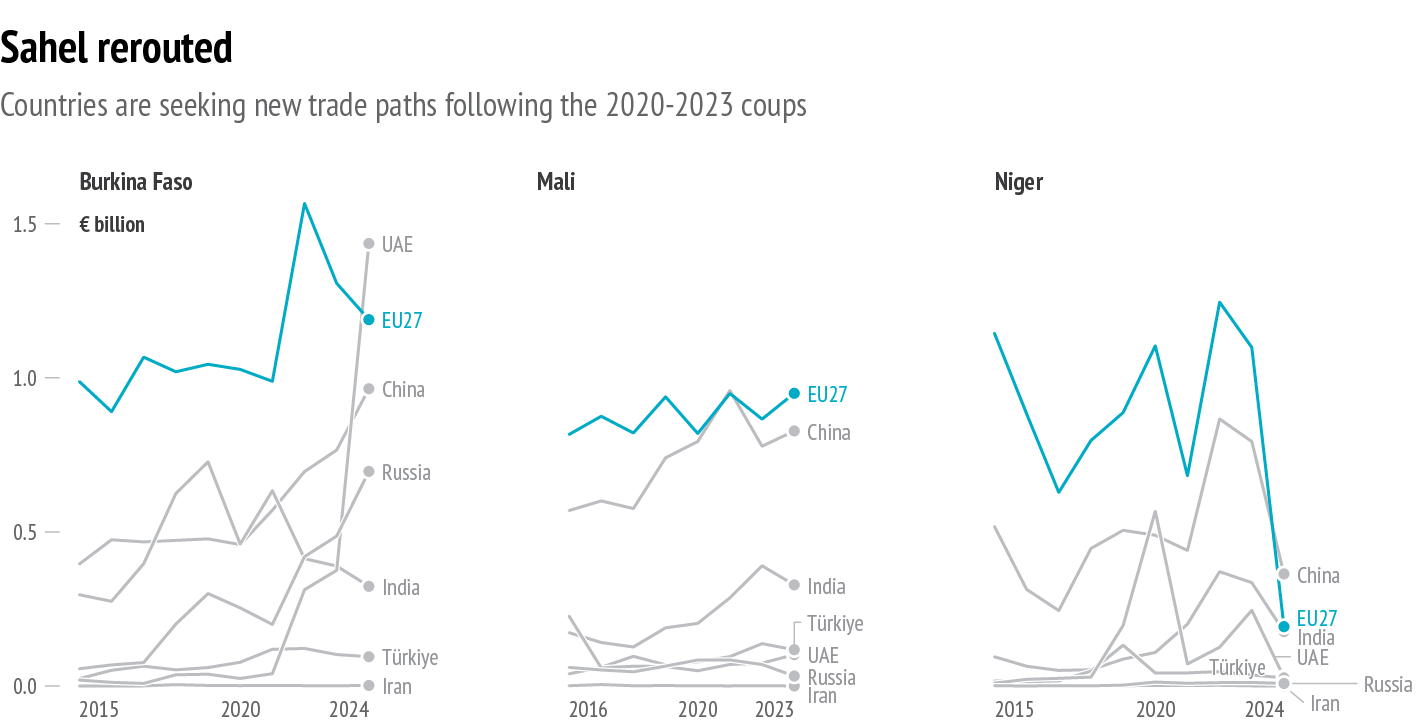

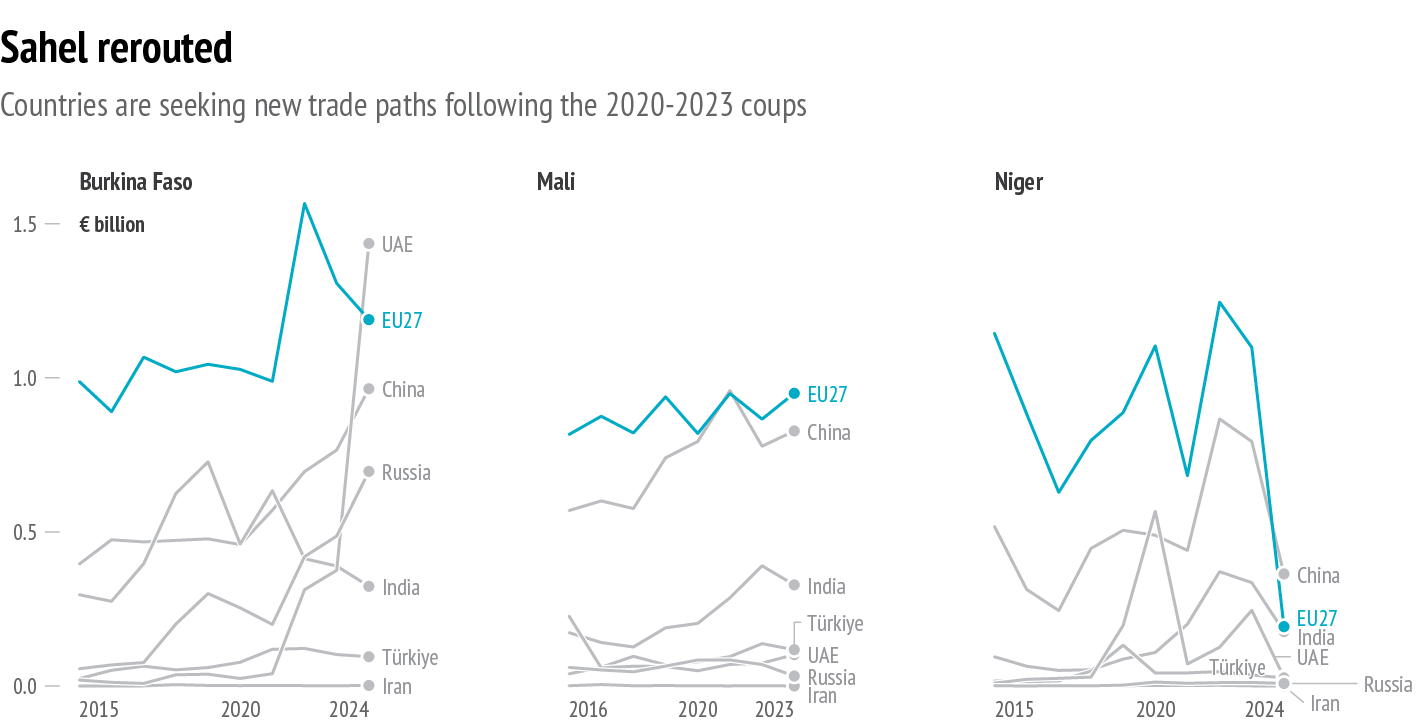

The Central Sahel maintained long-standing ties with partners such as Russia, China and Türkiye before the 2020–2023 coups. But the retreat of European countries following the wave of military takeovers created space for these ties to deepen and opened opportunities for new actors, like Iran and India, to engage with the countries of the Alliance of Sahelian States (AES), a defence pact formed by Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger in 2023. These developments mark a shift away from closer security cooperation with Europe and the US towards a posture of multi-alignment – signalling a changed landscape that presents new challenges for Europe.

This change reflects local narratives that blend criticism of past partnerships – especially with the UN, ECOWAS, France and the US – viewed by some as ineffective, especially in combating terrorism, with a determination to avoid isolation and forge new alliances. As a result, Sahelian states pursue foreign policies that prioritise regime preservation and maximise economic and security gains for elites, while external partners seek to advance their own national interests.

The Central Sahel remains vital for the EU due to its strategic location, the threats posed by terrorism, drug and human trafficking routes towards Europe, and international competition for resources such as oil, gold and uranium. Over the past three years, militant Islamist violence has caused an average of 10 500 deaths annually – seven times more than in 2019(1). In recent months, terrorist groups have demonstrated their ability to impose a fuel blockade on Bamako and to expand into neighbouring countries.

The EU should adopt a selective approach, avoiding confrontation while advancing its interests.

This Brief provides an overview of the changing international relations of the Central Sahel region by considering the multi-aligned foreign policy of the AES. China, Russia, Türkiye and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have emerged as key external players in this context, followed by India and Iran. For Europe, this evolving geopolitical landscape presents challenges, as multi-alignment can turn into a zero-sum game, jeopardising the EU’s stakes in the region. To mitigate this risk, the EU should adopt a selective approach, avoiding confrontation while advancing its interests.

Clout contest

While all non-Western actors in the Sahel operate under the banner of ‘multipolarity’, they each understand this notion differently. Russia seeks to restore its prestige as a global power; Iran aims to challenge the US and its allies; China focuses mainly on economic gains while countering US influence; and India aspires to a more prominent role in global politics. Meanwhile, Türkiye and the UAE seek to gain influence by balancing extensive economic investments with soft power, careful to avoid overt anti-Western rhetoric that could jeopardise their close ties with the EU and the US.

Russia has capitalised on the coups to position itself as a key partner of the new military regimes. Roughly 2 000 Russian fighters in Mali and several hundred in Burkina Faso and Niger have conducted combat and training missions. Russia thus seeks to present itself as a major independent security actor while discrediting Western partners through orchestrated media campaigns(2).

Moscow also targets the Sahel’s mining sector to fund its military operations and circumvent sanctions. The transition from Wagner to Africa Corps signals tighter Kremlin control, and is expected to shift the focus towards training in an effort to reduce casualties, remedy the reputational damage caused by Wagner’s brutality against civilians, and deflect responsibility for the expansion of the al-Qaeda-linked Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) into southern Mali. Cooperation has gradually expanded to infrastructure, energy and investment projects, but with limited results so far(3).

Data: International Trade Centre, Trade map, 2025

China anchors its presence primarily through its significant investments in the extractive sector, and its flagship Belt and Road Initiative. However, Chinese security contractors maintain a low profile, reportedly operating only in Mali, on a small scale. Beijing has also made a few military donations to these countries, including the reported delivery of 81 vehicles to Burkina Faso in 2024(4).

While already an established commercial and cooperation partner, Türkiye has expanded its security footprint, with reports indicating that Turkish companies have been deployed in Niger to protect mining assets. Turkish long-range medium-altitude long-endurance (MALE) drones Akinci and TB-2 now play a role in the Central Sahel countries’ counterinsurgency, intelligence and border protection operations(5).

The coups led the UAE to recalibrate its engagement in the Sahel, moving from support for the G5 Sahel Joint Force to deeper involvement in the gold sector. Between 2020 and 2024 gold exports from Burkina Faso and Niger to the UAE rose by 131%(6). Its position as a major destination for gold exports, combined with its activities in Islamic charity and education, allows the UAE to maintain strong visibility in the region.

India ranks among the top five commercial partners of the AES and has launched major cooperation projects in the region, including the establishment of the Mahatma Gandi conference centre in Niamey(7). New Delhi’s engagement in the Sahel reflects its broader outreach to the ‘Global South’, aimed at expanding its leadership role through scholarships, technical cooperation, and trade promotion(8).

By contrast, Iran has no commercial presence in the region, but prospects for increased security cooperation are emerging, especially in the light of Iran’s expanding drone industry and its interest in accessing Niger’s uranium reserves(9).

Multi-alignment vs. multipolarity

For their part, the AES states follow a multi-aligned approach rooted in the strong sovereignty claims of the Central Sahel governments and reflected in their preference for ‘diversifying’ partnerships. For example, despite having shallow trade relations with Iran, the three countries have invoked the legacy of the Iranian revolution and sent diplomatic delegations to Tehran to bolster their ‘revolutionary’ image(10).

Pragmatism has also led AES officials to court India, Türkiye and the UAE. Some European countries have maintained relations with the Central Sahel countries, notably Italy, which retains a small military mission in Niger, while EUCAP Sahel Mali remains active in Mali, and the US has begun to re-engage with the region(11). Türkiye’s defence cooperation benefits from the juntas’ reluctance to overly rely on China and Russia(12).

However, this logic of multi-alignment also creates tensions among partners. Competition over arms procurement has highlighted the emerging rivalry between Russia and Türkiye in the region. On 17 April 2025, the Russian media outlet African Initiative published an article accusing a Turkish think tank of spreading ‘anti-Chinese’ and ‘anti-Russian’ ‘propaganda’ in the context of the Sahel(13).

Elite access is another area of competition. Russia only recently reopened its embassies in Burkina Faso and Niger but retains influence through military training programmes and the activities of pro-Kremlin ‘pan-Africanist’ influencers who are close to the Nigerien de facto government, while Chinese citizens allegedly advise the Burkinabe leadership(14). Iran, for its part, has also stepped up its outreach to Sahelian states through an agreement on institutionalised security and defence cooperation with Niger and the opening of local branches of the Al-Mustafa International University – a sanctioned organisation accused of promoting regime ideology and recruiting for Iran‘s foreign legions(15).

At the same time, the AES countries are tightening control over the strategic mining sector, selectively providing access to external partners. In 2025, Mali and Niger increased pressure on Canadian and French companies, and three executives of the China National Petroleum Corporation were expelled from Niger as a row over salaries escalated(16). In 2022 and 2023, Bamako and Ouagadougou exercised caution about the potential involvement of Russian troops in their mining sector, seeking to avoid a repeat of the Central African Republic scenario, where Wagner reportedly ended up controlling a large portion of the industry. In Niger, Türkiye’s General Directorate of Mineral Research and Exploration announced the start of gold production in 2025(17).

A new balance in the EU’s strategy towards the Sahel

Non-Western actors are now important security and economic players in the Central Sahel. Given the region’s geographic proximity to Europe, and the EU’s goals of fighting terrorism, organised crime, trafficking and irregular migration, demographic projections estimating that the population will double to reach 154.4 million by 2051 make sustained engagement all the more urgent(18). The EU should therefore:

- Pursue a pragmatic approach vis-à-vis the Central Sahel countries. The EU should focus on a small and targeted set of areas for its engagement in line with the principles of the renewed approach adopted on 20 November 2025, such as justice, education and fighting organised crime. These provide ways to sustain EU influence, as well as the means to stay engaged.

- Adopt flexibility as a guiding principle. Multi-alignment in the Sahel entails constant negotiation between Sahelian governments and their external partners. While the EU’s Global Gateway strategy includes the Central Sahel in the complex settings envelope(19), the renewed approach to the region should restore the centrality of diplomacy in negotiating common interests, priorities and working methods to advance cooperation wherever common ground exists.

- Foster unity and coordination among the EU and Member States by aligning bilateral actions within a tailored country-by-country approach.

- Engage in partnerships with other countries whenever possible. Security in the region constitutes a priority not only for the EU, but also for neighbouring states, Türkiye, India, the UAE and China. The EU should therefore consider selectively engaging with these external players.

References

* The authors would like to thank Luca Guglielminotti, EUISS trainee, for his research assistance.

1 Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Africa surpasses 150,000 deaths linked to militant Islamist groups in past decade’, 28 July 2025.

2 Bryjka, F. and Czerep, J., ‘Africa Corps – a new iteration of Russia’s old military presence in Africa’, PISM Report, 23 May 2024.

3 Marangio, R., ‘Sub-Saharan Africa: Debunking the Russian mirage and strengthening EU-Africa ties’, in Ditrych, O. and Everts, S. (eds.), ‘Unpowering Russia: How the EU can counter and undermine the Kremlin’, Chaillot Paper No 186, EUISS, May 2025, pp. 47–55.

4 ‘Burkina Faso: la Chine octroie du matériel de soutien logistique à l’armée’, Burkina 24, 21 March 2024.

5 ‘Turkey adds mercenaries to Sahel’s violent mix’, Africa Defense Forum, 17 December 2024; Africa Center for Strategic Studies, ‘Drone proliferation in Africa: destabilising impact’, Africa Center Spotlight, 21 April 2025; ‘Turkey, Niger agree to enhance energy, defence cooperation’, Reuters, 18 July 2024.

6 Based on ITC, Trade map database.

7 ‘Jaishankar inaugurates convention centre in Niger dedicated to Gandhi’, Hindustan Times, 22 January 2020.

8 Embassy of India in Mali, Government of India, Factsheet on Mali, 19 August 2025.

9 ‘Iran courts Africa to ease isolation as it trails Russia, China and Turkey’, Al-Monitor, 20 August 2025.

10 Bouvier, É., ‘La présence croissante de l’Iran en Afrique’, Les clés du Moyen-Orient, 26 June 2024.

11 ‘Italy, Niger’s last Western partner’, Le Monde Afrique, 25 July 2024; Chason, R., ‘To fight extremists, Trump administration warms to Russia-friendly junta’, The Washington Post, 15 September 2025.

12 Wilén, N., ‘Stepping up engagement in the Sahel: Russia, China, Turkey and the Gulf States’, Egmont Policy Brief No 375, Egmont Institute, April 2025.

13 Ilin, M., ‘Kak Turtsiia pugaet Niger i ves Sakhel Kitaem i Rossiei ili obrazchik turetskoi propagandy’ [‘How Türkiye uses China and Russia to scare Niger and the entire Sahel, or an example of Turkish propaganda’], African Initiative, 17 April 2025.

14 ‘Séba promotes anti-French sentiments in West Africa’, African Digital Democracy Observatory, 12 January 2024; ‘Coopération Chine–Burkina Faso: des hommes d’affaires chinois et burkinabè échangent avec le Chef de l’État’, Le Faso, 20 September 2024; Byamungu, C-G. N., ‘Burkina Faso: un nouveau “prince” chinois près du capitaine président’, Le Projet Afrique Chine, 16 April 2025.

15 ONEP Niger, ‘Coopération sécuritaire Niger-Iran : signature d’un protocole d’accord relative à la mise en place d’un dispositif institutionnel’, Le Sahel, 9 May 2025; Government of Canada, ‘Canada imposes new sanctions against Iranian regime’, 31 October 2022.

16 ‘Niger expelled Chinese oil execs over local-expatriate pay gap, minister says’, Reuters, 20 March 2025.

17 ‘Turkish ministers head to Niger to boost ties’, Daily Sabah, 16 July 2024.

18 Authors’ elaboration based on data from UN Population Fund, World Population Dashboard, 2025.

19 European Commission, DG INTPA, Annual Activity Report 2024, March 2025, p. 30.