The launch of bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiations between the EU and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in April 2025 (1) marks a shift in the EU’s approach to engagement with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and its member states. After over three decades of stalled bloc-to-bloc talks, the EU is now pursuing a more flexible strategy. The shift goes beyond trade, reflecting a broader dual-track approach: advancing bilateral cooperation in the short to medium term while preserving the long-term goal of closer multilateral EU-GCC engagement. Ongoing discussions in Brussels on new partnership agreements between the EU and individual GCC member states illustrate this shift in practice.

The timing is deliberate. The negotiations come amid intensifying global trade uncertainty, driven by shifting US policy under Trump 2.0. While the EU’s 2022 Gulf Strategy provided a framework for renewed engagement, and 2024 brought visible momentum – including the first EU-GCC Summit – progress on core priorities has remained limited.

The EU has much to both offer and gain from a closer partnership with the GCC and its member states. But as Gulf states deepen ties with Asia, the EU must move beyond soft power narratives and vague declarations. Its engagement must be credible, offering stable markets, reliable investment, clear regulatory frameworks, and principled – but adaptable – diplomacy. Equally, it must be confident in asserting the strategic value it brings to the table.

Economic Engagement

Economic relations between the EU and the GCC have long alternated between multilateral and bilateral frameworks, with bilateral efforts often yielding more tangible results. Talks on an EU-GCC FTA, initiated in the 1990s, were suspended in 2008 due to ‘insurmountable differences in ambitions’ (2). Nevertheless, EU-GCC engagement has persisted through initiatives like the EU-GCC Dialogue on Trade and Investment (2017) and the EU-GCC Dialogue on Economic Diversification (2019).

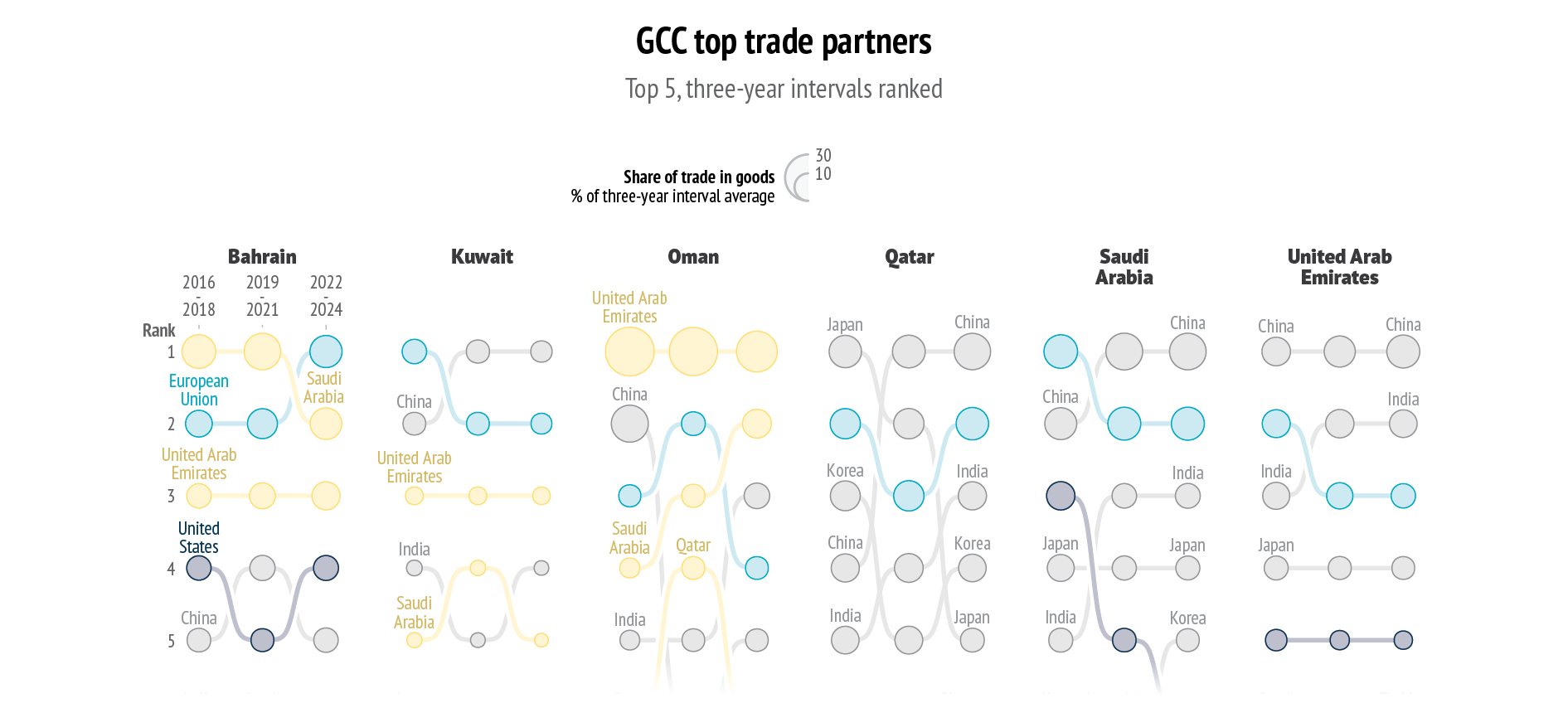

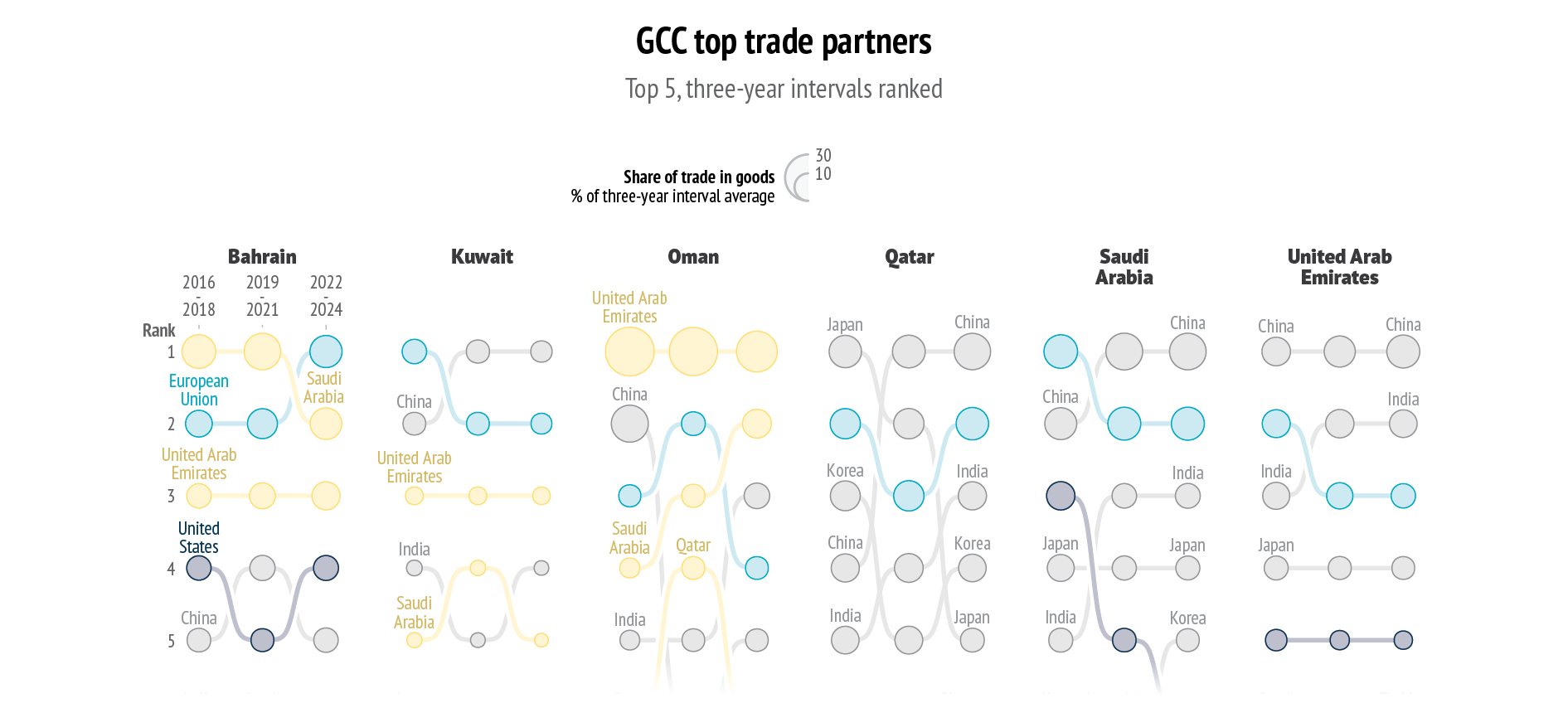

In the meantime, the trade landscape has evolved significantly, often to the EU’s detriment. As of 2024, the EU is no longer the leading trade partner for any GCC country, having ceded Bahrain to Saudi Arabia (3). China now holds the number-one spot in four of the six GCC states, while the EU ranks second in Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia. Yet rankings alone do not tell the full story. In Oman, for example, the EU ranks sixth – but accounts for 6.4% of total trade, more than its 4.4% share in Kuwait, where it ranks second. In Saudi Arabia, China overtook the EU in 2019, driven by rising Chinese exports rather than a decline in EU trade; by 2024, the EU’s trade share had rebounded to 15.6%, compared to China’s 18.7%. Overall, the EU has consistently maintained a positive trade balance with all GCC states.

Data: European Commission, Trade and Economic Security, Statistics, 2025

The investment landscape is mixed. Of the GCC’s 80 bilateral investment treaties, 22% are with EU Member States. Kuwait and the UAE lead on the GCC side, while France, Italy and Germany have treaties with all six GCC countries. Yet, despite headline deals like the $40 billion Italy-UAE partnership for 2025, actual investment flows remain modest.

While deals are negotiated at the Member State level, the EU’s collective weight enhances its appeal to GCC investors. Its stable economy is a key asset amid global uncertainty and rising US protectionism under the second Trump administration. Thanks to its market power and regulatory coherence, the EU remains a reliable, rules-based partner in an era of global tariff volatility. Meanwhile, multilateral cooperation remains viable in promoting trade and economic stability, including WTO governance and regulatory alignment in key sectors like transport.

Emerging Security Synergies

Security cooperation between the EU and the GCC is evolving in response to shifting geopolitical dynamics. Historically reliant on US security guarantees, many GCC states have begun to diversify their strategic partnerships following perceived inconsistencies in American engagement – particularly after the 2019 attacks on Saudi and Emirati infrastructure. While the EU is neither seen as, nor aspires to be, a substitute for the United States’ security role in the region, momentum for multilateral cooperation has grown.

The launch of the EU-GCC Structured Security Dialogue in 2024, followed by the second High-Level Forum in 2025, has helped institutionalise cooperation in key areas such as counterterrorism, maritime security, cyber and hybrid threats, and disaster response. The EU’s role in the Red Sea through Operation Aspides – tasked with protecting commercial shipping – signals its commitment to an issue of primary importance for GCC states. The recent cooperation protocol between the EU’s Emergency Response Coordination Centre and the GCC Emergency Management Centre, alongside logistical hubs like the ReliefEU stockpile in Dubai (4), marks a tangible step towards more structured inter-bloc collaboration.

However, significant obstacles remain. Both the EU and the GCC face internal divergences that hinder deeper cooperation. While the Gulf bloc has shown greater cohesion in recent years (5), particularly since the resolution of the Qatar crisis (2017–2021), differences persist over regional conflict strategies and preference for neutrality versus intervention. On the EU side, disunity driven by conflicting national interests, rising right-wing populism and internal political polarisation continues to limit its capacity to act as a cohesive strategic actor. Strategic divergences between the two blocs also persist, as GCC countries deepen economic ties with China and other Asian countries while hedging their positions on Russia and avoiding full alignment with Western sanctions.

While the EU has been sidelined in recent regional diplomacy over the Israel-Iran confrontation, the GCC states have shown they can play a stabilising role. Over the years, they have invested in easing tensions with Tehran, and now, wary of being drawn into a regional war, they have used their influence with the US to help de-escalate the conflict.

At the same time, the EU has identified targeted opportunities for engagement, notably through sanctions relief measures and humanitarian coordination with Saudi Arabia and Qatar in Syria and Yemen. The 2024 launch of the Global Alliance for the Implementation of the Two-State Solution, in partnership with Saudi Arabia and Norway, represents a rare example of joint leadership on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While it has yet to yield results and remains under-recognised, even in EU diplomatic messaging, it builds on one of the few points of consensus among EU Member States: that the two-state solution is the only viable resolution to the Israel-Palestine conflict.

Towards a green, AI-powered future

There is a clear shared interest between the EU and the GCC in advancing the digital transition and deploying smart technologies. A key aspect of this transition is the governance of data flows. Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE are attempting to position themselves as future digital hubs. Saudi Arabia is aligning itself closely with the US digital ecosystem, while the UAE, currently the largest investor in AI in the region and among the top 15 globally (6), has thus far sought to engage with both the US and China. Recent announcements indicating a strengthening of US-UAE cooperation in AI (7) suggest that the UAE may successfully maintain this dual approach, especially as the Trump administration appears to be easing chip export restrictions. Meanwhile, the EU has no current plans to relax its own export controls.

What the EU can offer in this domain is a human-centric approach to AI, grounded in long-term sustainability and committed to developing policies, standards and best practices that ensure robust ethical and legal frameworks (8). Closer coordination on AI governance, infrastructure and ethical standards would foster sustainable digital transformation in both regions and enrich the global debate on responsible AI.

The AI race further underscores the need for low-cost, green energy, another shared interest between the EU and GCC member states. However, expectations must be managed. It is unlikely that GCC countries will be able to export renewable energy at the scale the EU hopes for, especially from renewable and low-carbon hydrogen, at least in the short term. In the near to mid future, domestic consumption of renewables and continued oil exports may be more efficient and profitable for many GCC states, although this will vary by country.

Similarly, while the EU promotes the adoption of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies as part of its climate strategy, several GCC countries focus on Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR), a related but less climate-friendly method that uses captured CO2 to increase oil extraction. Although not aligned with the EU’s full decarbonisation goals, EOR-related infrastructure, if designed with long-term transition in mind, could eventually support carbon-negative production in a post-oil future.

While the EU and GCC countries take different approaches to the green transition, both can benefit from cooperation on clean technologies – an area where the EU has much to offer. Open and pragmatic dialogue about each side’s respective priorities is essential to avoid pursuing unrealistic or mismatched goals. Given differences in diversification strategies, pace of implementation, and oil and gas reserves across GCC countries, bilateral cooperation may be more effective than a uniform approach.

Building bridges

People-to-people relations are a key yet underutilised aspect of EU–GCC cooperation. Significant potential exists to strengthen bilateral ties through EU programmes such as Horizon Europe, Erasmus+ and TAIEX (9). Although all GCC member states qualify for participation in the latter programme – aimed at sharing public sector expertise – it has seen only limited uptake. with just a handful of TAIEX activities having taken place in Oman and Saudi Arabia (10).

In the research domain, GCC countries are not formally associated with Horizon Europe but are eligible to take part (11). Nevertheless, GCC institutions have been involved in just 32 projects under Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe combined, with most activity concentrated in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. In contrast, institutions from Morocco and Lebanon participated in 128 and 54 projects respectively, and Israel engaged in 1 662 projects under Horizon 2020 alone (12).

In 2022, EU universities hosted slightly over 9 000 GCC students, far fewer than the more than 30 000 enrolled in both the UK and the US (13). Erasmus+ exchanges between the EU and GCC have similarly been limited, often seeing more EU students travelling to the Gulf than vice versa.

To address these disparities, targeted initiatives promoting EU programmes are crucial. Establishing Horizon Europe contact points in all GCC countries – not just in Saudi Arabia and Oman – would significantly enhance participation (14). Although GCC higher education institutions are not currently included in the proposed Mediterranean University Network under the New Pact for the Mediterranean, incorporating them could significantly strengthen regional academic cooperation (15).

Conclusion

The evolving EU-GCC relationship reflects both the opportunities and limits of strategic cooperation in a rapidly changing global landscape. Since 2022, engagement has picked up speed, but asymmetries remain and priorities still diverge. The central challenge lies in balancing the EU’s preference for structured, multilateral frameworks with the GCC’s more flexible, state-led approach.

The political momentum is there, backed by increasingly active high-level exchanges. However, progress in bilateral cooperation on trade and investment, climate, and AI will depend on identifying concrete projects where interests already converge – or can be brought into alignment. Priorities include building consensus on decarbonisation pathways, strengthening academic and research collaboration, and supporting stability and development in the shared neighbourhood. The EU’s new dual-track strategy provides the flexibility to tailor cooperation – whether bilateral or multilateral – to the level of ambition on both sides.

References

* The author would like to thank Tamara Noueir for her research assistance.

- 1 European Commission, ‘EU and UAE agree to launch free trade talks’, 10 April 2025.

- 2 Ibid.

- 3 Author’s own analysis based on data from IMF.

- 4 EU Reporter, ‘Strengthening humanitarian partnerships: EU visits ReliefEU stockpile in Dubai’, 4 March 2025.

- 5 Ardemagni, E. and Barroug, H., ‘EU-GCC: Time looks ripe for security and defense cooperation’, ISPI, 15 October 2025.

- 6 Stanford University, ‘AI Index Report 2025’.

- 7 Reuters, ‘UAE to build biggest AI campus outside US in Trump deal, bypassing past China worries’, 15 May 2025.

- 8 European Commission, ‘European approach to artificial intelligence’.

- 9 The EU’s flagship research and innovation funding programme, and the largest of its kind globally; the EU’s programme for education, training, youth and sport; and an EU instrument for global institution building, respectively.

- 10 European Commission, ‘TAIEX and Twinning Highlights: Annual Activity Report 2023’.

- 11 From the broader MENA region Israel, Türkiye and Tunisia are associated to Horizon, and negotiations on Egypt’s association were concluded in April 2025 as well. See: European Commission, ‘Association to Horizon Europe’.

- 12 Cordis Database, ‘EU Research Results’.

- 13 ECD, ‘Number of mobile students enrolled and graduated by country of origin’.

- 14 Horizon Europe NCP Portal, ‘Find your NCP’.

- 15 European Commission, ‘Speech by President von der Leyen’, 25 May 2025.