The boundaries dividing the Maghreb and the Sahel have never looked so porous. Geography and history have long tethered North Africa to its southern hinterland. But a recent spate of coups and shifting diplomatic alignments has drawn the two regions into an even more intricate web of entanglements – albeit under markedly different terms. Globally, the US is cutting development aid but maintains strategic security ties in the region, particularly with Morocco. Russia remains engaged in the region, although its presence is increasingly contested locally.

In the central Sahel, regime changes in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger have upended long-standing foreign policy alignments. The trio’s rejection of more traditional partners such as France and the US in favour of alternatives – most notably Russia – has shifted the balance of power and redrawn the region’s diplomatic map. Yet this is not a clean break. What is emerging instead is a form of geopolitical hedging, in which states hedge their bets – strengthening some alliances while cautiously exploring others to minimise risk (1).

This pragmatic posture reflects a broader trend. As global and regional configurations evolve, governments are less inclined to commit fully to any single partnership. Instead, they weigh costs and benefits, test loyalties, and diversify partners to mitigate risks in an unpredictable world where flexibility has become a strategic virtue.

This Brief examines the changing relationship between the Maghreb and the Sahel through the twin lenses of shifting partnerships and strategic hedging. While realignments in partnerships are driven by a mix of domestic upheaval and global competition, hedging reflects a pragmatic stance aimed at achieving domestic goals while managing risks.

In this context, Europe would do well to adopt a more pragmatic and agile posture based on a new diplomacy-led approach to navigate regional dynamics.

Shifting partnerships

Between 2020 and 2023, Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger experienced five coups, altering domestic governance and reshaping their international alliances. The military juntas withdrew from the G5 Sahel, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), and the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF), and founded the Alliance of Sahelian States (AES) (2). Proclaiming a return to national sovereignty, the juntas have distanced themselves from traditional partners, chiefly France, and edged closer to Russia. Although European actors remain active in the region, their leverage has waned, especially in the aftermath of the coup in Niger.

In recent years, partnerships between Sahel and Maghreb countries have shifted. The coups in the central Sahel, along with renewed tensions between Algiers and Rabat over Western Sahara and intensified global competition, have triggered realignments across both regions.

Algeria, a key player in the region, has seen its relationship with Mali deteriorate, while it has stepped up efforts to strengthen ties with Niger.

Algeria’s relations with Mali soured after Bamako rejected the Peace Agreement and accused Algeria of interference through alleged support for Tuareg rebel groups. Imam Mahmoud Dicko’s continued presence in Algeria and Malian attacks against rebels near the Algerian border have further strained bilateral relations (3).

As Algeria’s relations with Mali have deteriorated, it has increasingly turned to Niger. Despite tensions over migrant expulsions from Algeria to Assamaka and Niger’s rejection of an Algerian proposal for a six-month transition, Niamey valued Algeria’s opposition to a foreign military intervention following the coup (4). Diplomatic and economic ties have since strengthened. Algeria’s state oil company, Sonatrach, has resumed oil exploration in Niger’s Kafra block and is collaborating on a petrochemical complex in Dosso and the Trans-Saharan Gas Pipeline (TSGP), which will connect Nigeria to Algeria via Niger and link to Europe. Over 200 Nigerien diplomats have also received training in Algeria, signalling deepening cooperation (5). Notwithstanding, on 6 April 2025 the AES countries issued a joint communiqué protesting over the alleged destruction of a Malian drone by Algeria and subsequently recalled their ambassadors (6). Niger’s shifting alliances also concern Libya, with the junta reportedly forging closer ties with the Tobruk-based Libyan National Army of General Haftar rather than the internationally recognised Government of National Unity, possibly with Russian support. In February 2025, Haftar’s forces captured a key figure associated with the Nigerien opposition in southern Libya (7).

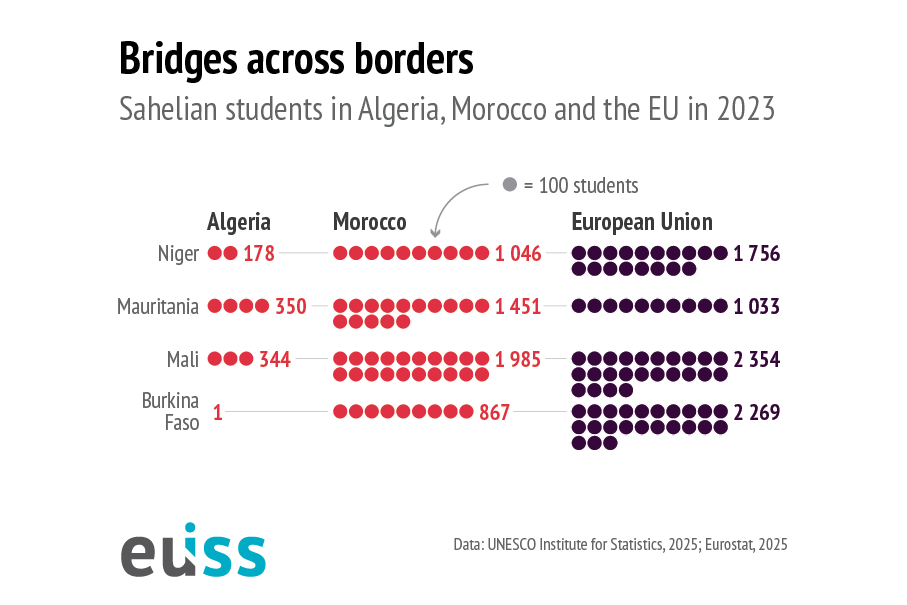

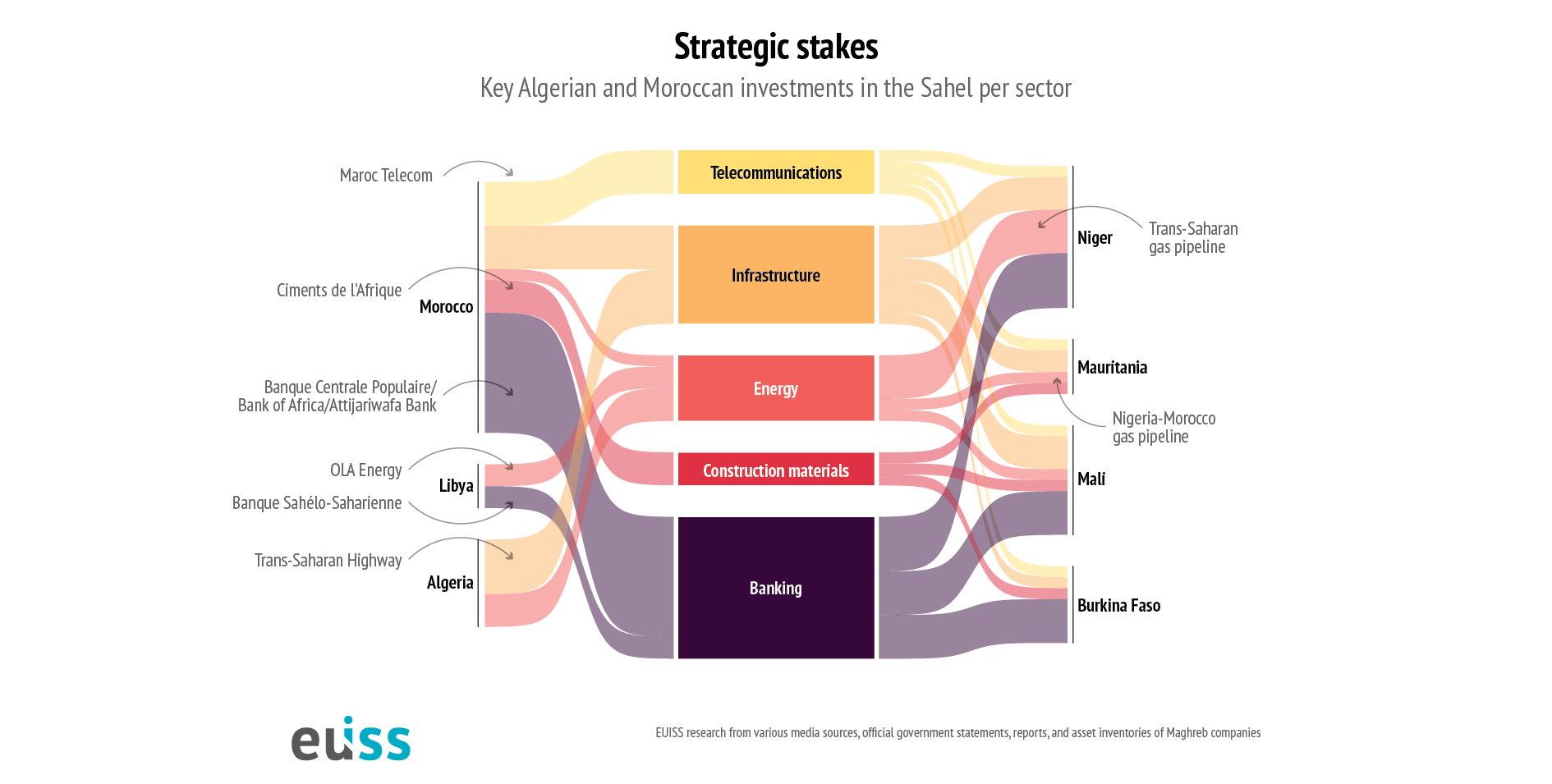

Rabat and Algiers, divided on the status of Western Sahara, appear to be projecting their competition for influence across the region. In contrast to Algeria’s renewed focus on Niger, Morocco has strengthened ties with all Sahelian states through trade, education, and infrastructure. Its educational initiatives, including training for students and military personnel, have boosted Morocco’s soft power. In 2023, Morocco hosted 21,000 African students, with 6,000 from Sahel countries (8). Morocco’s support of Sufi brotherhoods and religious institutions through the Mohammed VI Foundation of African Oulema, via the distribution of Qurans, mosque construction, and imam exchange programmes across Africa, further contributes to diplomatic rapprochement (9).

A key strategic project for Morocco is the Royal Atlantic Initiative, an offshore gas pipeline connecting Nigeria to Morocco, passing through several West African countries and providing Atlantic access to landlocked Sahelian states (10). This initiative serves both as an energy project and a geopolitical manoeuvre to strengthen ties across Western Africa and develop the port of Dakhla, reinforcing Morocco’s claims over Western Sahara. Endorsed by ECOWAS in late 2024, construction is set to begin in the northern section of the pipeline between Morocco and Senegal (11).

Mauritania maintains a position of ‘positive neutrality’ (12) on Western Sahara and fosters cooperation with both Algeria and Morocco. In 2024, Mauritania and Algeria launched a road project connecting Tindouf and Zouerate, along with plans to establish a duty-free zone to boost trade (13). In 2025, Mauritania and Morocco agreed to enhance cooperation in electricity, renewable energy, and strategic airline partnerships (14).

Hedging dynamics

As power dynamics shift, countries in the region use hedging strategies to diversify alliances and maximise both external and domestic benefits. Sahelian juntas prioritise regime survival by maintaining bilateral ties and fostering domestic dialogue to support prolonged transitions and suppress dissent. This approach helps mitigate isolation and the effects of shifting partnerships, such as limited engagement with traditional partners, reduced port access, and withdrawal from ECOWAS. Maghreb countries, particularly Algeria and Morocco, aim to expand their influence and outreach to the Sahel to offset limited regional integration and secure support or neutrality for their respective positions on Western Sahara.

Mali, for example, has welcomed Russian involvement primarily to combat terrorism, while focusing on consolidating state control and suppressing the rebellion, as shown by the symbolic ‘recapture’ of Kidal. This approach has strained relations with Algeria and Mauritania, opening space for Morocco to position itself as a more pragmatic partner. Morocco is strengthening its regional footprint through long-term projects like the Atlantic Initiative – which also positions it as a competitor vis-à-vis Algeria’s hydrocarbon exports to Europe. This is complemented by strategic investments in the banking system and telecommunications. Algeria has tried to increase cooperation with Niger to maintain its role in the Sahel region. However, the diplomatic crisis with Mali following the drone incident and the coordinated response of the AES has complicated this task. Meanwhile both Algeria and Morocco are courting Mauritania, offering expanding avenues for cooperation.

Thus, cooperation and competition are intertwined in the region as countries constantly adjust their positions, engaging in hedging strategies to maintain flexibility amidst shifting alliances. A key element of this approach is gauging each other’s intentions while keeping options open. The competition for sea and port access is critical, especially for landlocked Sahelian states seeking to overcome their geographical limitations. Morocco has positioned itself as a key partner in providing sea access, but it faces competition. Togo, leveraging tensions between Benin and Niger, is exploring its own port opportunities and allegedly considering joining the AES as control over trade routes can bring significant financial gains (15).

The recent withdrawal of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso from ECOWAS casts uncertainty over their exit from the common market. Yet, the introduction by the AES of a common 0.5% levy on imports looks like another hedging strategy as their membership of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA) also implies a common market. Thus, while the political rejection of ECOWAS after the coup in Niger serves the sovereignty argument, membership of the UEMOA mitigates economic risks. Hedging strategies have emerged as central tools of geopolitical manoeuvring, merging economic interests with shifting political dynamics. Trade, sea access and infrastructure projects like roads, pipelines, power grids and airlines are now vital for maximising profits and reducing reliance on any single partner.

Where to next?

Given the complex and fluid political landscape in the Sahel and Maghreb, the EU must adapt to the realities of shifting alliances. To navigate this environment, the EU should adopt flexible, diplomacy-led approaches that can accommodate countries’ hedging strategies while safeguarding European interests. This requires a three-pronged approach.

- Adopting a new diplomatic posture – less moralistic, more modular. The EU should discard binary notions of ‘ally’ and ‘adversary’. This mindset, subtly reflected in the EU’s posture towards countries like Niger and more explicitly echoed by Sahelian juntas, for instance in their stance towards France, limits the margin of manoeuvre. Instead, the EU should prioritise identifying shared interests and mutually acceptable modalities for engagement. Although Sahelian military regimes project unity under the rhetoric of sovereignty, their behaviour tends to be transactional and fluid.

- Focusing on feasibility and interests for the long term. This could include pivoting towards sectors that improve livelihoods, especially where security cooperation is not yet possible. Agriculture, water management, and decentralised energy projects can offer entry points for technical cooperation, helping to address underlying drivers of violent extremism and illicit activities. It may also imply looking for cooperation opportunities from the margins, such as increased cooperation with neighbouring states on education and security.

- Communicating its interests and red lines clearly and favouring selective cooperation. Hedging strategies show that countries in the region are weighing their options. The EU should prepare to focus on narrow, pragmatic cooperation instead of grand partnerships.

References

* The author would like to thank Ioana Trifoi, EUISS trainee, for her research assistance.

- 1 The theoretical discussion on the concept of ‘hedging’ is outside of the scope of this Brief. Several definitions of hedging have emerged in international relations theory, especially in South-East Asia and balance of power studies. See: Kuik, C.C., ‘Hedging in post-pandemic Asia: What, how, and why?’, The Asan Forum, 6 June 2020 (https://theasanforum.org/hedging-in-post-pandemic-asia-what-how-and-why/); Jones, D. M. and Jenne, N., ‘Hedging and grand strategy in Southeast Asian foreign policy’, International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, Vol. 22, Issue 2, May 2022, pp. 205–235 (https://doi.org/10.1093/irap/lcab003).

- 2 RFI, ‘Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso withdraw from French language body’, 20 March 2025 (https://www.rfi.fr/en/africa/20250320-mali-niger-and-burkina-faso-quit-international-francophone-organisation); ‘Le Mali, le Niger et le Burkina Faso instaurent un droit de douane commun’, Jeune Afrique, 30 March 2025 (https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1673759/politique/le-mali-le-niger-et-le-burkina-faso-instaurent-un-droit-de-douane-commun/).

- 3 RFI, ‘Nouveau regain de tension dans les relations entre l’Algérie et le Mali’, 7 January 2025 (https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250107-nouveau-regain-de-tension-dans-les-relations-entre-l-alg%C3%A9rie-et-le-mali); ‘Au Mali, le retour manqué de l’imam Dicko sous la menace des autorités’, Jeune Afrique, 14 February 2025 (https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1658485/politique/au-mali-leventuel-retour-de-limam-dicko-et-le-dilemme-des-autorites/).

- 4 RFI, ‘Niamey convoque l’ambassadeur d’Algérie pour protester contre le refoulement de migrants’, 5 April 2024 (https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20240405-niamey-convoque-l-ambassadeur-d-alg%C3%A9rie-pour-protester-contre-le-refoulement-de-migrants); RFI, ‘Niger: l’Algérie suspend sa médiation avec les autorités’, 10 October 2023 (https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20231010-niger-l-alg%C3%A9rie-suspend-sa-m%C3%A9diation-avec-les-autorit%C3%A9s).

- 5 Air Info, ‘Algérie-Niger : Une coopération stratégique et fraternelle au service du développement régional’, 25 February 2025 (https://airinfoagadez.com/2025/02/25/algerie-niger-une-cooperation-strategique-et-fraternelle-au-service-du-developpement-regional/).

- 6 ‘Le Mali, le Niger et le Burkina Faso rappellent leurs ambassadeurs en Algérie après un incident avec un drone’, Le Monde, 7 April 2025 (https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/04/07/le-mali-le-niger-et-le-burkina-faso-rappellent-leurs-ambassadeurs-en-algerie-apres-un-incident-de-drone_6592160_3212.html).

- 7 RFI, ‘Niger: Mahmoud Sallah, le chef du Front patriotique pour la libération, arrêté en Libye’, 24 February 2025 (https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20250224-niger-mahmoud-sallah-le-chef-du-front-patriotique-pour-la-lib%C3%A9ration-arr%C3%AAt%C3%A9-en-libye).

- 8 UNESCO, Institute for Statistics Data Browser page (https://databrowser.uis.unesco.org/browser).

- 9 Czerep, J., ‘Morocco’s religious diplomacy drives its expansion in Africa’, PISM, 12 January 2021 (https://pism.pl/publications/Moroccos_Religious_Diplomacy__Drives_Its_Expansion_in_Africa).

- 10 Lyammouri, R. and Ghoulidi, A., ‘Morocco’s Atlantic Initiative: A Catalyst for Sahel-Saharan Integration’, PCNS Policy Brief–No 68/24, 10 December 2024 (https://www.policycenter.ma/sites/default/files/2024-12/PB_68-24_Rida%20Lyammouri.pdf).

- 11 ECOWAS, Joint Meeting of the Energy and Hydrocarbons Ministers of the ECOWAS Member States, Extended to Include Morocco and Mauritania, on the Nigeria-Morocco African Atlantic Gas Pipeline Project, 4 November 2024 (https://ecowas.int/joint-meeting-of-the-energy-and-hydrocarbons-ministers-of-the-ecowas-member-states-extended-to-include-morocco-and-mauritania-on-the-nigeria-morocco-african-atlantic-gas-pipeline-project/).

- 12 UNSC, ‘Report of the Secretary-General: Situation concerning Western Sahara’, S/2024/707, 1 October 2024, p. 5 (https://minurso.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/sg_report_on_the_situation_concerning_western_sahara_1_october_2024.pdf).

- 13 RFI, ‘Entre Algérie et Mauritanie, le lancement de nouveaux projets pour renforcer leur partenariat’, 23 February (https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20240223-entre-alg%C3%A9rie-et-mauritanie-le-lancement-de-nouveaux-projets-pour-renforcer-leur-partenariat).

- 14 Le360Afrique, ‘Royal Air Maroc et Mauritania Airlines concluent un partenariat stratégique’, 4 April 2025 (https://afrique.le360.ma/economie/royal-air-maroc-et-mauritania-airlines-concluent-un-partenariat-strategique_PQXVVK7WMBGZPOFVMP3WGWDNDQ/); Morocco, Ministry for Energy Transition and Sustainable Development, ‘Le Maroc et la Mauritanie signent un protocole d’accord pour développer leur partenariat dans les secteurs de l’électricité et des énergies renouvelables’, 23 January 2025 (https://www.mem.gov.ma/Pages/actualite.aspx?act=548).

- 15 ‘Le Togo multiplie les appels du pied en direction des juntes de l’Alliance des Etats du Sahel’, Le Monde, 21 March 2025 (https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2025/03/21/le-togo-multiplie-les-appels-du-pied-en-direction-de-l-alliance-des-etats-du-sahel_6584256_3212.html).