The EU needs a playbook to protect civil societies under pressure in its wider neighbourhood. It must find a credible way to champion liberty and the rule of law while confronting the rise of authoritarian strongmen. These leaders, seeing the liberal order under strain, believe that they can secure benefits by aligning with illiberal powers like Russia and China – often to the detriment of their own societies. Georgia, a membership candidate state where the consolidation of authoritarian rule looks likely to intensify following a contested parliamentary election last month, provides a critical testing ground for developing such a strategy.

Failure to act will cost the Georgian people their liberty and transform the region into a battlefield for competing third powers. It will also represent a major failure of the EU’s Eastern policy, which aims to expand the area of democracy, security and prosperity. This Brief first provides an analysis of recent developments, before listing the options that the EU should consider to avert such an outcome.

Explaining the outcome of the election

The parliamentary election in Georgia on 26 October marked another milestone in the dramatic deterioration of the relationship between the government and the EU that resulted in the de facto halting of the accession process in June (1). In the election, the Georgian Dream (GD), a party founded and dominated by the billionaire Bidzina (formerly Boris) Ivanishvili, claimed a fourth consecutive victory. According to the Central Election Commission, the GD received 53.93% of the vote and will have 89 representatives in the 150-seat parliament. It won in every electoral district except Tbilisi and Rustavi. In large swathes of the countryside, it obtained more than 60% of the vote according to official statistics (2).

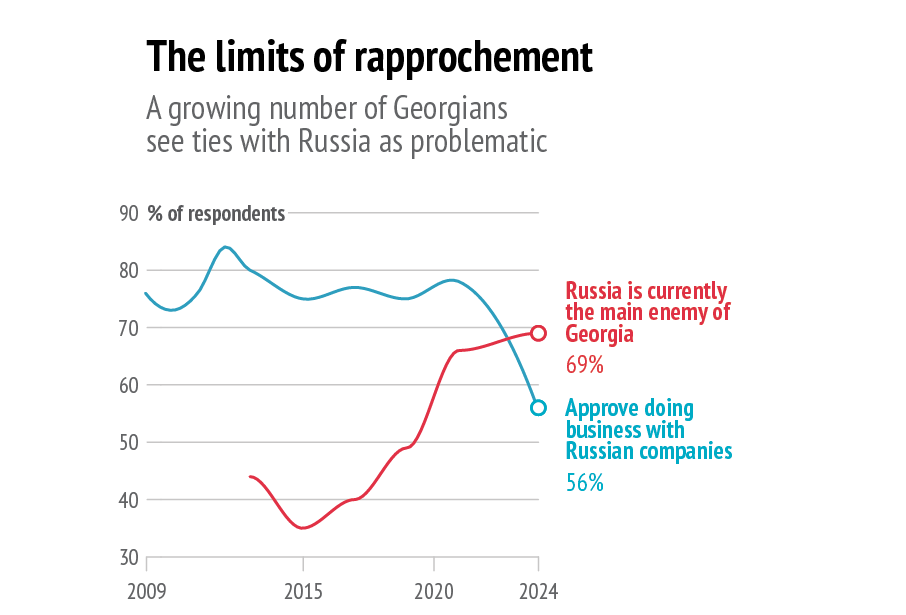

Data: Caucasus Barometer, 2024

The opposition claims that the GD orchestrated widespread fraud and stole the election. As a result, they have refused to take up their seats in the new parliament, calling for an international inquiry while organising protests at home. It is beyond dispute that the election was marred by procedural irregularities, including compromised ballot secrecy, fraudulent identification practices, intimidation of voters and local electoral committees, as well as the misuse of administrative resources and deeply polarising rhetoric by the government ahead of the vote (3). The official results are also inconsistent with the GD’s previous polling and exit polls (4). While it is unlikely that the vote tampering directly robbed the opposition of victory, it almost certainly secured a majority of seats for the GD in the new parliament.

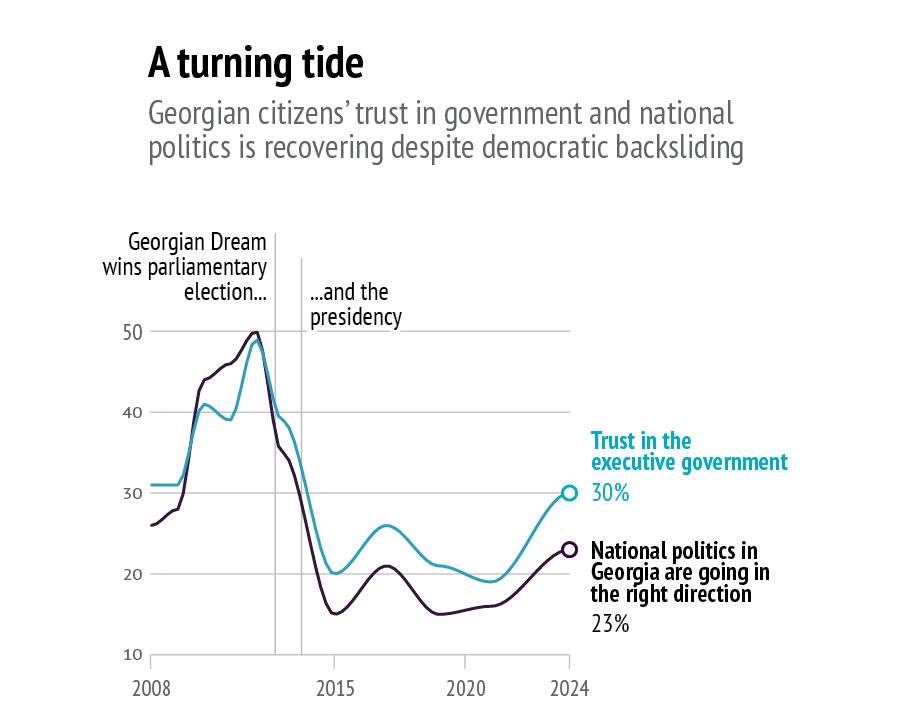

The current crisis should be read as a prelude to the culmination of a long-term process of state capture and the consolidation of an illiberal, authoritarian government in Georgia. This process aims to dismantle the constraints on the power of Ivanishvili and his inner circle imposed by institutional checks and balances, as well as by the political opposition and civil society. A violent crackdown on both the opposition and civil society involving mass repression, incarceration and intimidation is, unfortunately, not an unthinkable scenario. A more likely outcome however, one that averts the risks that direct confrontation would entail for the government, is the gradual entrenchment of illiberal authoritarianism, primarily achieved through indirect albeit no less insidious tactics. This would involve further suppression of civic activity and political pluralism, while tightening control over the army and police, subjecting the latter to more complex oversight and developing more stringent coup-proofing measures. Replacing President Zourabishvili with a more compliant successor when her term in office ends will grant the GD control over the last independent major state institution in the country.

A more likely outcome of the elections is the gradual entrenchment of illiberal authoritarianism.

The election results that have led to these outcomes are not solely due to electoral manipulation. They also reflect a significant level of genuine popular support for the GD. This support is driven by the relative economic stability the government promises and delivers, as well as deep political polarisation – which has long been a staple of Georgian politics (5). It has recently been accentuated by the GD’s divisive rhetoric and conspiracy narratives, which portray the government as a defender of peace and traditional values while depicting the opposition as criminals and enemies of the state acting on behalf of the ‘global war party’. The latter allegedly seeks to open a second front in the war between Russia and Ukraine (6). While this inflammatory rhetoric has undeniably boosted support for the GD, the popularity enjoyed by the party may ultimately also be ascribed to the opposition’s failure to unite and reach out to the wider populace – notably in the regions – with a credible message.

The role of the Kremlin in orchestrating the election manipulation, as claimed by the opposition, is more difficult to establish. Relations between Georgia and Russia were all but normalised under the GD’s rule despite Russia’s occupation of 20% of Georgia’s internationally recognised territory. Moscow lifted the ban on direct flights and suspended visa requirements in 2023, while the Russian Federation Interests Section (СЕКЦИЯ ИНТЕРЕСОВ) in Tbilisi, operating under Swiss auspices, functions as an embassy in all but name. It is not unlikely that Georgia will, in the foreseeable future, join the ‘3+3’ regional cooperation platform that it has so far boycotted due to Russia’s participation (7).

But it is also a marriage of convenience, making life easier for Ivanishvili who is ready to embrace the Kremlin’s paranoid political style but is not prepared to accept Russia’s dominance. Meanwhile, Moscow benefits from the deteriorating relations between Georgia and the EU as well as the US without having to invest substantial resources in subversive hybrid operations as, for example, in Moldova.

The government's geopolitical hedging

Ivanishvili’s core interest is, simply, securing his own absolute power – which he sees as essential for protecting his wealth and personal safety. He has no intention of allowing his power to be curtailed by reforms which the EU has demanded, including the repeal of recent controversial laws. Paradoxical as it may seem, the recent wave of accusations and disinformation from the GD directed at the EU is a direct consequence of Georgia’s drawing closer to the EU – the process the GD has notionally overseen to respond to the European aspirations of the populace, but which it has in fact hindered, if not sabotaged (8). The GD was willing to finalise the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) because these posed no challenges to its power. But it only applied for membership after some hesitation in 2022, after Ukraine and, more importantly Moldova, had already expressed their intent to do so – and may have miscalculated the dynamics of the enlargement process that followed.

Data: Caucasus Barometer, 2024

To safeguard and protect the political system it has created, the GD’s geopolitical strategy is one of hedging. It shops for useful ‘goods’ wherever possible – in the EU from which it seeks financial support and legitimacy vis-à-vis the population, but equally by engaging with Russia, China, Iran, Türkiye or the Gulf states. However, this approach may turn out to be misguided. As the influence of these powers grows, so too will the structural pressures on the country’s autonomy. No single individual’s negotiating skills can keep these countervailing pressures under control. Unlike Azerbaijan, Georgia does not possess significant material resources. In the past, it often suffered from external empires jostling for power and influence in the region. But for the time being, the GD seems relatively comfortable with the current state of affairs. It sees little value in the (now increasingly elusive) prospect of opening accession talks. It must continue to engage the population, for whom the EU embodies prosperity and ‘Westernness’ to avoid a crisis of legitimacy that, in Georgia’s political culture, could easily escalate into unrest and instability. However, it can sustain this façade for a while longer, under the banner of the slogan ‘to Europe, with dignity’ (9).

The response playbook: Punish, protect, progress

In response to the ongoing process of democratic backsliding, the EU has de facto halted the accession process, redirected €121 million in unspent assistance away from the state, and frozen European Peace Facility (EPF) funding. Member States also agreed to deploy a small technical mission composed of EU officials to Georgia in the aftermath of the election.

However, a consensus on other measures has been difficult to achieve. Under these circumstances, the EU must resist the temptation to restore normal relations in exchange for minor concessions in the coming months. This would only bolster the government’s domestic legitimacy, as well as provide a licence for further repression.

Instead, the EU should respond with greater resolve. Contrary to widespread belief, it has a number of other response options available to it even in the absence of unanimity. Its approach should combine the ‘3Ps’ of punitive, protective and progressive countermeasures.

An anaemic response to the recent backsliding will be interpreted by the government as a sign of weakness and will only embolden it further. Therefore, sanctions should be implemented by individual Member States, or by coalitions of willing states and partners, targeting Ivanishvili and his inner circle. Furthermore, the EU and Member States should take a firm stance by not scheduling any future Association Council meetings or high-level political dialogues, and by suspending the DCFTA. The EU is Georgia’s largest trading partner, even if – as with other partners – the latter has been running a significant trade deficit (10). Moreover, the EU should halt all direct budgetary support and technical cooperation while Member States should agree not to provide any bilateral funding that contributes to the government’s operations. Last but not least, it should immediately suspend Schengen visas for all diplomatic passport holders, an option proposed in an EEAS options paper released in June.

Little fish

The 'other' parties in Georgia and their official vote share

Coalition for Change

11.03%

This coalition is made up of Akhali, Girchi-For More Freedom, Droa, the Republican Party of Georgia, and the Activists for the Future Movement. Akhali and Droa were established after the 2020 elections, while Girchi had previously participated in the 2020 elections, obtaining 2.89% of the vote. The Republican Party, one of Georgia's oldest political groups, has never contested elections independently, always joining an electoral coalition. Its four leaders are Nika Gvaramia, Nika Melia, Zurab Japaridze, and Elene Khoshtaria.

Unity-National Movement (U-NM)

10.07%

The Unity-National Movement coalition is composed of the United National Movement (UNM), the party of former President Mikheil Saakashvili, as well as the Strategy Agmashenebeli Party and the European Georgia Party. The leaders of this coalition are Tina Bokuchava (UNM) and Giorgi Vashadze (Strategy Agmashenebeli).

Strong Georgia

8.81%

This coalition, composed of Lelo for Georgia, the For the People party, the Citizens Party, and the Freedom Square Movement, brings together new figures in politics and former officials from the Georgian Dream. Lelo is led by Mamuka Khazaradze, co-founder of Georgia's largest bank, TBC Bank. For the People is led by Ana Dolidze, an international law professor who was appointed to the High Council of Justice in 2018 by the President of Georgia. The Freedom Square Movement is led by Levan Tsutskiridze, founder of the Eastern European Centre for Multiparty Democracy (EECMD).

Gakharia For Georgia

7.78%

The party was founded and is led by former prime minister Giorgi Gakharia. It includes former officials and deputies from the Georgian Dream, some of whom held positions in ministries and law enforcement agencies. Through this party, Gakharia aims to provide a third alternative to the polarised political landscape, which has been shaped by the rivalry between the U-NM and the GD. However, his role in the violent crackdown on demonstrations during his time as interior minister in 2019 hampers his ability to distance himself from his previous record.

Data: Civil Georgia, 'Amid Brawls and Protests, CEC Announces Final Results, Stamps GD Victory', 11 Nov 2024; CEPA, 'Fractious Opposition Puts Georgia’s Future in the Balance', 16 Sep 2024.

The EU must also deploy measures to defend civil society. It should focus on helping civil society organisations to resist mounting pressures (for example, by providing legal assistance) as well as countering the stigma imposed by the foreign agent law. It should also assist these organisations in building capacities to communicate more effectively with the public – which supports stability but also overwhelmingly favours democracy (11). It can moreover foster creative strategies to protect the space for freedom, including through developing robust strategies to combat disinformation and foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI).

Any future steps towards normalising relations with the government should be contingent on genuine and sustainable reforms, and the removal of government pressure on civil society. The EU should double down on efforts to develop closer ties with the Georgian people by reallocating funds towards the empowerment of a free media and civil society – not as a mere ‘sector’, but rather as an independent space that fosters freedom and authentic human expression. The EU should also increase efforts at building societal resilience at the local level, helping communities to reduce their dependence on the captured state and the clientelist network it sustains.

In the absence of a robust system for manufacturing ideological consensus, the government will likely continue to rely on ‘output legitimacy’. It is possible, therefore, that future economic shocks, potentially coupled with disillusionment with the new third power patrons – including Russia – and their growing influence, may lead it to adopt a more accommodating approach towards the EU. At that point, the regime’s fear of destabilisation, combined with incentives the EU can offer, may force some concessions on its part. However, the political system created by the GD remains fundamentally incompatible with the expectations placed on a new EU Member State. Whatever leverage the EU possesses, or can muster, should be used to protect Georgian civil society and the remaining space of freedom from which genuine resistance to authoritarian practices can emerge. Ultimately, democratic change will have to come from the people – as is the case elsewhere in the wider neighbourhood. Here too, the EU’s approach should combine the ‘3Ps’ to defend freedom. This should form a central component of a truly geopolitical strategy that stands firm on values and intensifies efforts to promote them.

References

* The author would like to thank Carole-Louise Ashby for her invaluable research assistance.

1. European Council, Conclusions, 27 June 2024 (https://www. consilium.europa.eu/media/qa3lblga/euco-conclusions- 27062024-en.pdf).

2. Results published by the Election Administration of Georgia (CEC), 26 October 2024 (https://results.cec.gov.ge/#/en-us/ election_57/tr/prop).

3. ENEMO, ‘Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions’, 27 October 2024 (https://enemo.org/storage/uploads/ rrYDUP6R8d74XmSV93InFTckSB3ViDCkKIc9D20H.pdf); OSCE-ODIHR, ‘Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions’, 27 October 2024 (https://www.osce.org/files/f/ documents/3/0/579346.pdf).

4. Edison Research, ‘Analysis of discrepancy between exit poll and CEC results’, 1 November 2024 (https://www. edisonresearch.com/edison-research-2024-republic-of- georgia-exit-poll/); HarrisX, ‘Final Exit Poll Analysis’, 31 October 2024 (https://www.harrisx.com/content/harrisx- final-georgia-2024-exit-poll-analysis).

5. For a historic overview of the polarising rhetoric see: Ditrych, O., ‘Georgia: A state of flux,’ Journal of International Relations and Development, Vol. 13, No. 1, February 2010, pp. 3-25.

6. EDMO, ‘“Global war party“, “Second front”, “Unprecedented election meddling” from the West, and other propaganda narratives dominating Georgian information space in the run-up to the key 2024 elections’, 25 October 2024 (https:// edmo.eu/publications/global-war-party-second-front- unprecedented-election-meddling-from-the-west-and- other-propaganda-narratives-dominating-georgian- information-spa/).

7. The platform now includes Russia, Türkiye, Iran and the other South Caucasus republics.

8. For example, the case of Nika Gvaramia, the former director of Mtavari Arkhi television station (and now the head of the opposition Ahali party), who was sentenced to three and a half years in prison for abuse of power in May 2022; the introduction (and later reintroduction) of the transparency (‘foreign agent’) law; amendments to the tax code and electoral framework that disregarded the recommendations of ODIHR and the Venice Commission, and the adoption of the ‘family values’ law targeting minorities – all of which were criticised by the EU.

9. Georgian Public Broadcaster, ‘PM: By 2030, Georgia will become EU member with dignity, respect for Christianity, Church, morals’, 23 October 2024 (https://1tv.ge/lang/en/ news/pm-by-2030-georgia-will-become-eu-member-with- dignity-respect-for-christianity-church-morals/).

10. European Commission, ‘EU trade relations with Georgia’ (https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships- country-and-region/countries-and-regions/georgia_en).

11. Caucasus Barometer, ‘ATTDEM: Attitude towards democracy‘, Survey question, 2024 (https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb- ge/ATTDEM/).