Vladimir Putin’s aggression against Ukraine has once more turned the Black Sea into an arena of confrontation between a resurgent Russia and the West. The United States and the European Union have thrown their collective weight behind the defence of Ukrainian sovereignty, the military effort aimed at liberating Russian-occupied territories, and restoring Ukraine’s control over its territorial waters and economic zone in the Black and Azov Seas. As the conflict unfolds, Türkiye (1) remains very much a ‘swing actor’. Like the rest of NATO, it backs Ukraine. However, the Turkish leadership has refused to cut economic and diplomatic ties with Moscow, much less join the increasingly harsh sanctions imposed against Russia. Indeed, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan aspires to be a go-between in the conflict, mediating between the warring sides. At the same time, Türkiye is keen to exploit Russia’s weakness in order to expand its influence in and around the Black Sea.

This Brief starts with a section exploring Türkiye’s pre-war geopolitical posture, both generally and with specific reference to the Black Sea. It then focuses on the Turkish response to the ongoing war in Ukraine and its evolution over time. The third part examines the role Türkiye plays in the Southern Caucasus, while the fourth section analyses the implications for the EU and the West more broadly. Lastly, the conclusion recapitulates the main findings and puts forward policy recommendations concerning the Union’s policy towards Türkiye.

Türkiye’s pre-war position in the black sea

Türkiye’s approach to the Black Sea is influenced by geography, history, the changing international environment and its own domestic politics.

Of all Black Sea countries, Türkiye has, de facto, the longest coastline – 1 329 km in total. That is less than Ukraine’s 2 782 km, but the latter includes both Crimea, illegally annexed by Russia in 2014, and the Azov Sea coast which is likewise under Russian occupation since the fall of Mariupol last May. Moreover, Türkiye literally holds the key to the Black Sea by virtue of controlling the Bosporus and the Dardanelles, the passage to the outside world through the Mediterranean. The Turkish government enforces the Montreux Convention (1936) regulating the maritime traffic through the Straits. Ankara sees this international legal instrument which limits external powers’ access to the Black Sea as paramount to national security and has scrupulously stood by its provisions over time, including during World War II and the current hostilities in Ukraine.

Thanks to its imperial history, Türkiye has extensive relationships with all other countries bordering the Black Sea: diplomatic contacts, trade and investment ties, the presence of sizeable diasporas on Turkish soil, as well as Turkish, Turkic, or Muslim communities residing in neighbouring states, such as Crimean Tatars, Adjarians in Georgia, or Moldova’s Gagauz community. Türkiye is in the unique position of belonging to both the Balkans/Southeast Europe and the Caucasus, two of the regions flanking the Black Sea. Last but not least, prominent figures in Turkish politics and society have strong ties to the region (2).

The end of the Cold War allowed Türkiye to rekindle historic ties and stake a claim for leadership in the Black Sea. With the Soviet Union gone, the balance of power tilted towards Ankara, boosted by its special relationship with Washington. It opened opportunities initiated by President Turgut Özal. By the 2000s, even Moscow had overcome its initial suspicion vis-à-vis Türkiye harbouring ambitions to expand its foothold in the Southern Caucasus and Central Asia, or indeed into Muslim-majority regions of the Russian Federation. The Russian leadership forged closer links with Ankara, with strategic projects such as the Blue Stream undersea gas pipeline cementing the partnership.

Türkiye responded to the resurgence of Russian power under Putin with pragmatism. It embraced the notion of the Black Sea as a Russian-Turkish condominium. This is why Ankara was not supportive of proposals to give NATO a greater role in maritime security advanced by Romania (which joined the Alliance in 2004) and parts of the Bush administration in Washington. During the Russian invasion of Georgia in August 2008, Türkiye delayed the passage of US naval vessels delivering supplies through the Straits and invested in mediation efforts. It pursued a similar policy in the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea in 2014. While denouncing the annexation (to this day), voicing support for Crimean Tatars (considered a kin ethnic group) and their exiled leaders, and deepening political and defence ties with Ukraine, Türkiye continued engaging with Russia and refused to join Western sanctions. Even at the height of the Russian-Turkish spat over Syria in 2015-6, Erdoğan did not give unequivocal support to suggestions to upgrade NATO’s naval presence in the Black Sea.

This posture in no small part reflects the sea change in Türkiye’s self-image under AKP rule over the past two decades (3). Rather than a peripheral member of the Western alliance, Türkiye sees itself as an autonomous power intent on pursuing its own national interest in a multipolar world where US hegemony is in decline. The impasse in membership talks with the EU, the authoritarian shift in Turkish politics after the 2016 coup attempt, and the installation of a presidential regime has contributed for trade (notably the export of construction services), investment, and multilateral engagement through the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (BSEC) organisation to this reorientation. Erdoğan’s foreign policy is about balancing between the West and revisionist players like Russia and China.

The end of the Cold War allowed Türkiye to rekindle historic ties in the Black Sea.

In the Black Sea, Türkiye is arguably following a policy of ‘soft balancing’ Russia. On the one hand, the relationship between Putin and Erdoğan is going from strength to strength – especially in co-managing regional conflicts such as Syria, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh, and now Ukraine. The same applies to energy relations, with the undersea TurkStream gas pipeline operating since January 2020. Yet Türkiye has also scored points against Russia: for example by helping Azerbaijan win a resounding victory against Armenia, an ally of Moscow in the (near defunct) Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), in Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020, while it is now working to normalise relations with Yerevan. Ankara has doubled down on the triangular relationship with Georgia and Azerbaijan, key to the Southern Gas Corridor which diversifies supplies to Europe. It also backs NATO’s ‘open-door’ policy which makes Ukraine and Georgia eligible for membership. Most importantly, Türkiye has signed extensive defence contracts with Ukraine in the past number of years, a fact which came into the spotlight thanks to the use of Turkish drones by the Armed Forces of Ukraine (ZSU) in resisting Russian aggression.

Türkiye and the war in Ukraine

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has raised the geopolitical and economic stakes for Türkiye. It has highlighted the danger of Russian expansionism but also provided opportunities for Ankara to reassert Türkiye’s status as a leading geopolitical player to tip the regional power balance against Russia, and to reset relations with the West, which had deteriorated since the failed coup in 2016.

The stakes for Türkiye

Russia’s actions challenged Türkiye directly. In the early days of the war, the prospect of the erasure of Ukrainian sovereignty coupled with the extension of Russian control over the entire Black Sea coast, all the way to Odesa, threatened to upend the post-Cold War status quo in the region. Once again, as after the complete absorption of Abkhazia and South Ossetia (2008) and, even more importantly, Crimea (2014), the Russians looked poised to chip away at the territorial buffer that separated them from Türkiye’s borders. Turning Ukraine into a landlocked country would have disadvantaged Ankara greatly as it would tilt the balance in Russia’s favour. It would have severed direct links between the port of Odesa and the Turkish littoral, downgrading Türkiye’s security position and economic ties to Kyiv.

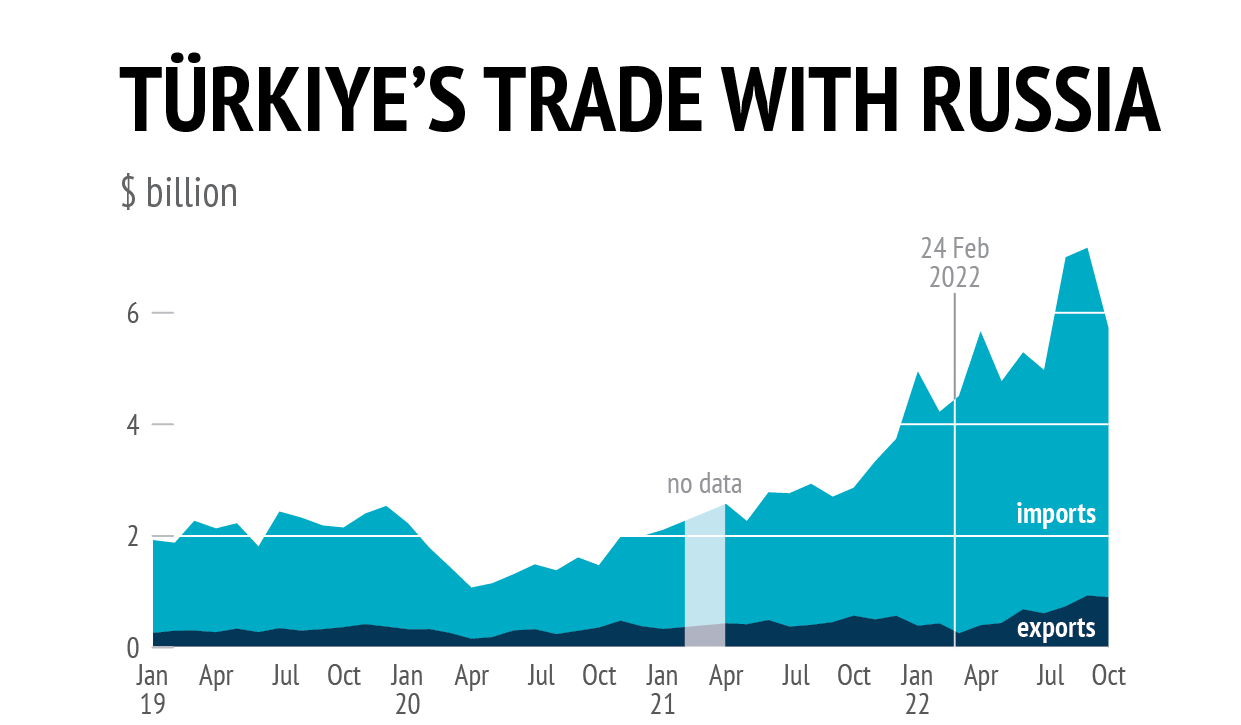

Data: Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2022

Fortunately for Türkiye, the war has not delivered a decisive victory for Moscow, due to the bungled political strategy behind the invasion, the stiff resistance put up by the ZSU and the massive Western support to Kyiv. The defeat of the early Russian onslaught against the Ukrainian capital (February-April) and the subsequent retaking of large swathes of territory in eastern and southern Ukraine, notably the city of Kherson (9-11 November), turned the tide. Russian forces have been expelled from the Mykolaiv oblast’ and part of the Kherson oblast’ and pushed to the left bank of the Dnipro River. This means that the major port of Odesa appears to be safe, despite the constant Russian attacks on civilian infrastructure.

Yet the war generates not just geopolitical but serious economic risks and knock-on effects as well. Due to the weakening Turkish lira and annual inflation running at 85.5 % according to official estimates (and perhaps more than double that figure, according to independent watchdogs and economists) (4), Türkiye has been vulnerable to fluctuations of energy and food prices. The looming recession in the EU, driven in part by the drastic reduction of Russian gas supplies leading to soaring energy prices, has implications for Türkiye too. The country’s economy is dependent on the EU for trade and foreign direct investment (FDI). Economists expect growth to slow down from a decade-high of 11 % in 2021 to just 3 % in 2023, well below official projections of 5 % (5).

Stakes for Erdoğan

The economy is Erdoğan’s Achilles heel and a reason to stay on good terms with Russia.

It is hard to overestimate the president’s influence over the formulation and conduct of Turkish foreign policy (6). His personal ties to Putin have shaped the way in which a series of regional crises, starting from Crimea to Nagorno-Karabakh, have been managed. Without him at the helm, Ankara would have been much less accommodating of Moscow, though it is by no means a given that a different government or leader would have backed the Western sanctions and confronted Russia.

Since 24 February 2022, Erdoğan has been sticking to business as usual, with regular phone calls and meetings between him and Putin (7). Engaging Russia and acting as a go-between makes sense from a domestic politics perspective. Erdoğan’s chief priority is winning the forthcoming elections in May 2023. Having a stable relationship with the Kremlin as well from the war (e.g. budgetary support, trade, Russian financial assets transferred to Türkiye to evade sanctions) could prove instrumental for winning the presidential re-election bid and ensuring that the AKP retains its parliamentary majority.

Managing the Türkiye-Russia-Ukraine triangle

Against all odds, Erdoğan has fared relatively well since the outbreak of the war, balancing between the West and Russia and minimising the negative fallout on the economy and domestic politics.

Türkiye's support for Ukraine

The Turkish response to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine echoed its reaction to the crisis of 2014-5. Like then, Erdoğan opposed any attempt to change the territorial status quo. As happened after the annexation of Crimea, Türkiye denounced the ‘referendums’ in September 2022 aimed at legalising the occupation of Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk and Luhansk by Russia. ‘Lands which were invaded will be returned to Ukraine’, Erdoğan declared. Türkiye voted alongside the West in the UN General Assembly resolutions condemning the war. In a show of support, Erdoğan visited Lviv to meet President Zelensky on 18 August.

Türkiye has been trying to tip the balance of power against Russia in various ways. Ankara has been providing Ukrainians with arms, including the TB2 Bayraktar unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) which were highly valued during the defence of Kyiv in the first stage of the war, and laser-guided missiles (8). The government-backed firm, run by President Erdoğan’s son-in-law, scored yet another PR coup when it donated three more UAVs to Kyiv in June. This delivery follows the sale of 20 Bayraktar drones before 2022, and an order for another 16 in January 2022, weeks before the invasion (9). Ukraine has also been cooperating with MILGEM, Türkiye’s national naval programme. In October, the Hetman Ivan Mazepa corvette was launched in Istanbul; it will be further equipped before being delivered to Ukraine (10).

In addition, the Turks have been applying the Montreux Convention strictly. In March, Turkish authorities closed the Straits to naval ships, making it impossible for Russia to reinforce its Black Sea fleet whose flagship, the Moskva, was sunk by the Ukrainians on 14 April. In late February, in the immediate aftermath of Russia’s invasion, the Turkish authorities refused to allow four naval vessels through the Dardanelles. In early November, it prevented the passage of two more ships from Russia’s Pacific fleet, the missile cruiser Varyag and the anti-submarine vessel Admiral Tributs, through the Straits (11).

Türkiye has extended support to Moldova, which is exposed to the conflict in next-door Ukraine too. Early in the conflict, a Turkish NGO sent aid to Ukrainian refugees on Moldovan territory. A parliamentary delegation led by Speaker Mustafa Şentop visited the Gagauz region in September. In the near future, Türkiye could supply Moldova with gas through the so-called Vertical Corridor following the route of the Transbalkan Pipeline (12).

Engagement with Russia

At the same time, Türkiye has refused to confront Russia and burn its bridges with Putin. In the words of analyst Galip Dalay, ‘Türkiye is trying to be pro-Kyiv without being overtly anti-Moscow’ (13). Indeed, Erdoğan has continued to engage with Putin and to act as a go-between with both Kyiv and the West, starting with a visit to Ukraine’s capital on 3 February – weeks before the Russian assault.

Türkiye has sought to gain economic benefits from the war. It has left the door open to nearly 200 000 middle-class Russians who have found refuge in Istanbul, Antalya and other coastal towns. Certain Istanbul neighbourhoods such as Kadıköy have sizeable Russian populations. Oligarchs close to the Kremlin, including blacklisted individuals, who reportedly ‘parked’ their assets in Türkiye, have found safe haven in the country (14). More than three million Russian tourists holidayed in Turkish resorts over the summer of 2022. Big business deals such as the Rosatom contract to build the country’s first nuclear power stations or the gas-supply arrangements with Gazprom have proceeded as in peacetime. Türkiye may have received budgetary support from the Kremlin too, amounting to €30 billion in direct transfers and another €20 billion in deferred payments from the state-owned utility company BOTAŞ to Gazprom (15).

In addition, Turkish exports to Russia have surged. According to the Turkish Statistical Institute, from May to July 2022, Türkiye exported USD 2.04 billion, compared to USD 642 million over the same period in 2021. This increase has raised concern about Türkiye providing a backdoor for Russia to bypass Western sanctions (16). In late September, Turkish banks withdrew from the Mir payment system set up by Moscow, fearing secondary sanctions by the United States (17).

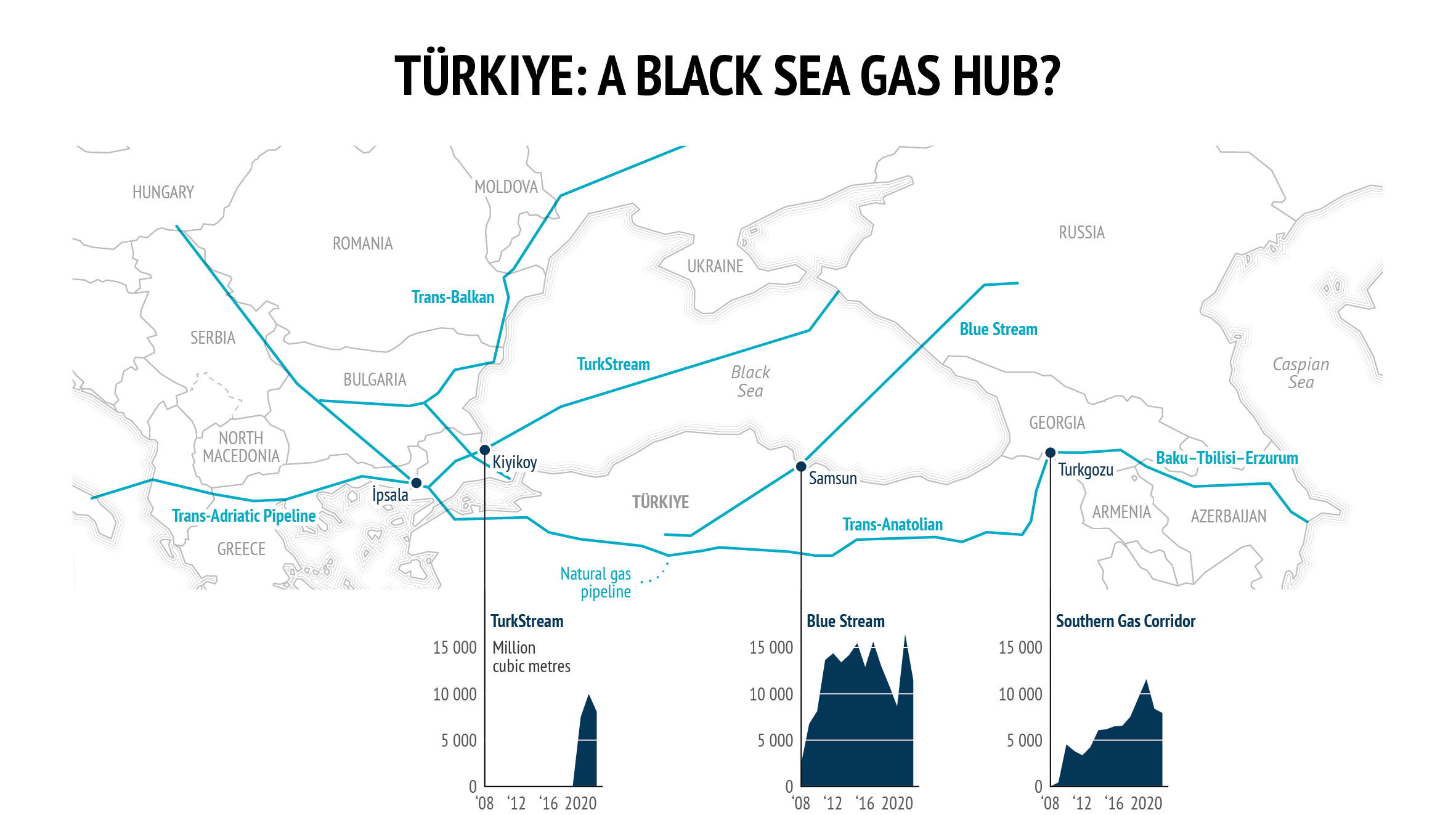

Ankara continues to receive the same volumes of gas as before the invasion, via the TurkStream and BlueStream pipelines crossing the Black Sea (18). Moreover, Putin himself touted, on 12 October, the prospect of turning Türkiye into ‘a gas hub’ (19). That implies that Gazprom is willing to sell BOTAŞ additional volumes beyond the quotas under the long-term agreements they have signed. Türkiye will be then able to resell the extra gas to customers in the EU and parts of the neighbourhood. Whether this is a realistic prospect or a political ploy by the Kremlin to boost Erdoğan’s popularity before a hotly contested election remains to be seen. What remains to be seen too are the commercial and technical aspects of a prospective deal, especially given that BOTAŞ’ long-term contracts with Gazprom will be expiring at the end of 2025.

Türkiye plays an important role regarding Russian crude oil. The EU ban on seaborne imports of oil from Russia, effective from 5 December onwards, has complicated matters. Turkish authorities demand that tankers transiting the Bosporus en route to international markets provide proof of insurance, which Western companies issue to tankers only if the Russian crude they carry is sold at the capped price of USD 60 per barrel. Whether Türkiye relaxes the rules or not will have an impact on Moscow’s ability to generate revenue from oil, traditionally the main source of revenue for Russian state coffers.

Türkiye's mediation efforts

Türkiye’s strategic position and Erdoğan’s priorities explain why Turkish diplomacy has switched to higher gear.

On 10 March 2022, foreign minister Mevlüt Çavuşoglu hosted a meeting between Sergei Lavrov and Dmytro Kuleba, his opposite numbers from Ukraine and Russia, on the margins of a conference in Antalya.

Then, David Arakhamia and Vladimir Medinsky, appointed as mediators by Kyiv and Moscow, met in Istanbul on 29 March. Neither of those meetings yielded any tangible result, such as a ceasefire in Ukraine. After the discovery of the Bucha massacre, negotiations were suspended.

The Southern Caucasus is central to Türkiye’s policy in the wider Black Sea region.

Türkiye’s efforts to broker a deal on grain exports from Ukraine led to a breakthrough. On 22 July, Sergey Shoigu, the Russian defence minister, and Oleksandr Kubrakov, Ukraine’s transport and infrastructure minister, agreed to establish ‘a grain corridor’ from the ports of Chornomorsk, Odesa, and Yuzhny/Pivdennyi for a period of three months, subject to renewal. In the presence of Erdoğan and the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, the two sides signed two parallel documents. Under their terms, officials from Türkiye, Ukraine, Russia, and the UN were to inspect ships crossing the Bosphorus en route to Odesa at a Joint Command Centre (JCC) in Istanbul to verify they were not carrying any weapons. Both sides committed not to attack commercial ships. The Ukrainians agreed to remove sea mines in the waters around Odesa, laid there to prevent an amphibious assault.

Data: Global Energy Monitor, 2022; International Energy Agency, 2022; European Commission, GISCO, 2023

Türkiye attaches great value to the grain corridor (20). It is essential for its own food security but also enhances the country’s international prestige. The notion of Türkiye as a leader of the Global South, especially Muslim-majority countries in the Middle East and Africa, looms large in the AKP and Erdoğan’s foreign policy rhetoric. Those countries have been particularly vulnerable to food inflation driven by the disruption of grain supplies from Ukraine and Russia, two leading exporters. Thus far, the deal has defied sceptics and remained in place, with up to 10 million tons of grain shipped out of Ukraine in its first three months (21). On 29 October, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs declared that Moscow was withdrawing from the deal in response to Ukrainian drone strikes against the Black Sea fleet in Sevastopol. However, on 2 November, the agreement was renewed after talks between Turkish and Russian defence ministers Hulusi Akar and Sergey Shoigu. Ukraine failed to obtain a counter-concession to add Mykolaiv as a fourth port from which grain could be safely shipped (22).

Türkiye on the eastern shores of the black sea

The Southern Caucasus is central to Türkiye’s policy in the wider Black Sea region. The 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war allowed Ankara to encroach into what Russia considers ‘a privileged sphere of influence.’ Although Moscow remains the principal arbiter in the area and was able to put ‘boots on the ground’ in Azerbaijan through a peacekeeping contingent deployed along the line of contact, it yielded gains for Ankara as well.

Türkiye has used the momentum to pursue rapprochement with Armenia. The restoration of Azerbaijan’s control over six adjacent regions bordering Nagorno-Karabakh proper removed a pre-condition Ankara had stipulated in 2010 for normalising ties. To Armenia, the war showed Russia’s limitations as a security guarantor, in that Moscow failed to deter Baku from resorting to military aggression (23). That is why President Nikol Pashinyan, re-elected in a landslide victory in June 2021 despite the military defeat, sought to diversify the country’s foreign policy beyond the patron-client relationship with Russia.

The conflict in Ukraine accelerated diplomatic negotiations. On 12 March, foreign minsters Ararat Mirzoyan and Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu met on the margins of the Antalya Diplomatic Forum. Then, on 7 October, Erdoğan and Pashinyan held a historic meeting during the inaugural summit of the European Political Community (EPC) in Prague. Significantly, the gathering put the West and Türkiye in the same camp in dealing with the dispute, while isolating the Russians (24).

The critical test, however, is whether Türkiye and Armenia will be able to establish diplomatic relations and open the border, closed since the early 1990s. The new escalation around Nagorno-Karabakh, where hostilities have restarted and where Azerbaijan is now blocking the Lachin Corridor connecting Armenia proper and the breakaway region, is ominous. (25). The Armenian leadership fears that President Ilham Aliyev is using Russia’s embroilment in Ukraine to put extra pressure on Yerevan. Pashinyan has been calling on Russia and the CSTO to step in and fulfil their peacekeeping obligations. Meanwhile, Baku is accusing Yerevan of failing to honour its commitment to open the so-called Zanzegur Corridor through Armenia proper to Azerbaijan’s Nakhichevan exclave bordering Türkiye (26). So long as tensions continue unabated, Turkish-Armenian rapprochement will be put on hold. This in turn will hinder the EU’s ongoing efforts to facilitate conflict resolution, in cooperation with Ankara (27).

Türkiye’s relationship with Azerbaijan and Georgia has been much more cordial. For the Azeris, Ankara is a strategic ally as well as an important market and conduit for hydrocarbon exports. The presence of the Nationalist Action Party (MHP) in the governing coalition, a force committed to pan-Turkism, further cements the relationship and goes some way towards explaining the intervention in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. For Georgia, Türkiye provides a vital link to the West and a friend within NATO.

The three countries have banded together in strategic projects such as the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway, part of the so-called Middle Corridor connecting Türkiye to China via Central Asia, and the Southern Gas Corridor. The latter has received a great boost from the war in Ukraine and the volatility on international energy markets triggered by Russia’s aggression. The Southern Gas Corridor connects Azerbaijan to Greece and Italy and, as of last autumn, serves Bulgaria too, covering one-third of the consumption in the country. The Southern Gas Corridor could double its capacity too and be linked to the Western Balkans through interconnectors between Bulgaria and Serbia (under construction) as well as Greece and North Macedonia. Its annual capacity, 16 billion cubic metres (bcm) at present, could increase (28). Russia’s decoupling from Europe and the resulting deficit in the European gas market will drive interest in Azerbaijan as an alternative supplier, with Türkiye playing a key role as a transit link.

Implications for the EU

The war in Ukraine affects Türkiye’s relations with the EU. Ankara has been trying, mostly with success, to maintain a maximum degree of autonomy from the West. Yet it is also a potential beneficiary of the greater commitment by the EU and US to the Black Sea.

One of the longer-term consequences of the war in Ukraine could also be the further ‘EU-isation’ of the Black Sea. Ukraine and Moldova have been granted candidate status. With the exception of Russia, all regional countries, including Armenia and Azerbaijan, are also part of the EPC. Both collectively and at the level of individual Member States, the EU is supporting Ukraine financially as well as with arms and materiel. In the long run, there is little doubt that the Union will be underwriting post-conflict reconstruction – through its budget but also by coordinating assistance from other international donors.

The question is where Türkiye stands with respect to the region’s European integration. Its relationship with the EU is complex, with some Member States seeing Ankara as a threat and others favouring cooperation. However, in the Eastern neighbourhood, there is no reason why Ankara should be at odds with the EU. Brussels’ agenda on economic integration, trade, investment, and infrastructure development benefits Turkish interests and particularly business. That includes stakeholders in the influential construction sector, close to Erdoğan, which has an impressive track record in the area since the 1990s.

Going forward, Ukraine’s reconstruction will provide lucrative opportunities. On 18 August, during Erdoğan’s trip to Lviv and his meeting with President Volodymyr Zelensky, Turkish Trade Minister Mehmet Muş and Ukrainian Infrastructure Minister Oleksandr Kubrakov signed an MoU on the issue. Turkish companies are repairing the bridge at Irpin, near Kyiv, and are interested in projects in and around Kharkiv (29). In sum, a three-way partnership between Ukraine, Türkiye and the EU, as the principal donor, may emerge in the years to come.

Türkiye is already playing a key role in efforts to diversify gas supplies away from Russia. Black Sea countries such as Bulgaria are already taking advantage of BOTAŞ’s LNG terminal at Ereglesi on the Corridor. A long-term supply contract is in the works that could see Bulgargaz importing volumes from Türkiye. Others can benefit too, including Romania, Moldova and Ukraine which are all connected through the so-called Vertical Corridor – that is, the currently disused Transbalkan Pipeline. Türkiye will also be significant in the development of renewable sources – solar, offshore wind and geothermal – serving its own energy needs but also the neighbourhood.

Conclusion

Türkiye’s post-Cold War policy in the Black Sea was based on the vision of a Russian-Turkish duopoly of power. The two major regional powers would safeguard security and stability, while excluding Oktay Lubinets Malkoc outsiders such as the US and, to a lesser degree, the EU. These dynamics were demonstrated as recently Marmara Sea, in addition to the Southern Gas as the autumn of 2020 when Putin and Erdoğan mediated in the Nagorno-Karabakh war. Türkiye and Russia underwrote a ceasefire between Azerbaijan and Armenia, bypassing the OSCE Minsk Group, which also has France and the US as members, in dealing with the conflict.

Already eroded by the annexation of Crimea, which led to Erdoğan’s warning that the Black Sea was turning into ‘a Russian lake’ (30), this model of Russo-Turkish partnership has now lapsed thanks to Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. A new dividing line is cutting through the Black Sea and its northern littoral. Ukraine is firmly in the Western sphere and Moldova is gravitating towards it as Moscow is upping political and economic pressure on the pro-EU government in Chisinau. Russia has lost credibility in Armenia, its closest ally in the region, and its influence over Azerbaijan and Georgia is not as strong as in the past. The EU and Türkiye have joined forces to mediate in Nagorno-Karabakh – so far, with no success. In addition, Putin has doubled down on territorial revisionism, threatening the post-1991 order to which Türkiye has subscribed. From a Turkish perspective, the sovereignty and independence of ‘buffer countries’ is a sine qua non for national security. In sum, Türkiye now has to deal with a much less stable and predictable environment.

Despite deepening divisions and the Kremlin’s expansionism, Türkiye will continue to maintain, to the extent that this is possible, equidistance from Russia and the West in order to assert its strategic autonomy. Although it will show support for Ukraine, Ankara will not be pushing for a full defeat of Russia as this would diminish its own geopolitical weight and the leverage it holds vis-à-vis the United States and its European allies. Regardless of whether Erdoğan wins the presidential race in the spring, or a new leader emerges, the current course of Turkish foreign policy is unlikely to change significantly.

Having acknowledged these realities, the EU should identify areas where cooperation with Türkiye is possible and indeed desirable. Ukraine is clearly the most important item on the agenda. For all its flaws, the grain deal Türkiye could be of critical help to Kyiv. Future reconstruction of Ukraine will provide even greater opportunity for coordination and cooperation with the EU and its Member States in helping the Ukrainians. Although the European integration of the Black Sea is a long-term project, the incremental steps along the way, in areas such as infrastructure development, diversification of energy sources and the green transition, would benefit from enlisting Türkiye’s support.

References

1. In line with the request of the Republic of Türkiye regarding the use of the country’s new official name in English, this publication uses the name ‘Türkiye’ instead of ‘Turkey’.

2. The two best examples are President Erdoğan, whose family hails from the town of Rize near the border with Georgia, and the opposition mayor of Istanbul (by far the largest metropolis on the Black Sea shores) Ekrem Imamoğlu, who was born in Akçaabat next to the port city of Trabzon.

3. Bechev, D., Turkey under Erdoğan: How a country turned from democracy and the West, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2022.

4. Fırat Büyük, H., ‘Inflation rate continues to skyrocket in Turkey’, BalkanInsight, 4 April 2022 (https://balkaninsight.com/2022/04/04/ inflation-rate-continues-to-skyrocket-in-turkey/).

5. ‘Turkey’s inflation seen at 42.5 % in 2023, GDP growth at 3 %’, Reuters, 17 January 2023 (https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkeys-inflation-seen-425-2023-gdp-growth-3-2023-01-17/).

6. ‘Turkey has a newly confrontational foreign policy’, The Economist, 16 January 2023 (https://www.economist.com/special-report/2023/01/16/ turkey-has-a-newly-confrontational-foreign-policy).

7. Erdoğan met with Putin in Tehran during a three-way summit on 19 July hosted by the Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi. It was followed by talks in Sochi on 5 August, and a conversation on 16 September during the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, and on 13 October in Astana, Kazakhstan.

8. Soylu, R., ‘Turkey supplied laser-guided missiles to Ukraine’, Middle East Eye, 23 November 2022 (https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/ turkey-supplied-laser-guided-missiles-ukraine).

9. Soylu, R., ‘Ukraine received 50 Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones since Russian invasion’, Middle East Eye, 28 June 2022 (https://www. middleeasteye.net/news/russia-ukraine-war-tb2-bayraktar-drones- fifty-received).

10. Özberk, T., ‘Turkish shipyard launches Ukraine’s 1st MILGEM corvette’, Naval News, 3 October 2022 (https://www.navalnews.com/naval- news/2022/10/turkish-shipyard-launches-hetman-ivan-mazepa/).

11. Navy Recognition, ‘Türkiye refuses to let two Russian warships enter the Black Sea’, 7 November 2022 (https://www.navyrecognition.com/index. php/naval-news/naval-news-archive/2022/november/12448-tuerkiye- refuses-to-let-two-russian-warships-enter-the-black-sea.html).

12. Moldova 1, ‘Turkey could offer the Republic of Moldova a new gas route’, 7 December 2022 (https://moldova1.md/p/731/turkey-could-offer-the- republic-of-moldova-a-new-gas-route).

13. Dalay, G., ‘Ukraine’s wider impact on Turkey’s international future’, Chatham House, 10 March 2022 (https://www.chathamhouse. org/2022/03/ukraines-wider-impact-turkeys-international-future).

14. İnce, E., Forsythe, M. and Gall, C., ‘Russian superyachts find safe haven in Turkey, raising concerns in Washington’, The New York Times, 23 October 2022 (https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/23/world/europe/ russian-superyachts-find-safe-haven-in-turkey-raising-concerns-in- washington.html).

15. Akman, B. ‘Turkish foreign reserves jump after Russian money transfer’, Bloomberg, 5 August 2022 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2022-08-05/turkish-foreign-reserves-jump-after-russian- money-transfer).

16. FT Reporters, ‘Surge in Turkish exports to Russia raises Western fears of closer ties’, The Financial Times, 16 August 2022 (https://www.ft.com/ content/caee1ae3-41c5-4c85-8d66-a8d3eea3112d).

17. Sezer, C., ‘Turkey’s state banks suspend use of Russian Mir payment system – finance minister’, 29 September 2022 (https://www.reuters. com/business/finance/turkeys-ziraat-bank-suspends-use-russian-mir- payment-system-ceo-2022-09-29/).

18. In December 2021, BOTAŞ and Gazprom signed a four-year contract covering the deliveries of gas through the TurkStream pipeline.

19. Gaber, Y., ‘Turkey can become an energy hub – but not by going all-in on Russian gas’, Atlantic Council, 7 December 2022 (https://www. atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/turkeysource/turkey-can-become-an-energy- hub-but-not-by-going-all-in-on-russian-gas/).

20. Turkey has also mediated in prisoner swaps between the US and Russia and Ukraine and Russia. It hosted a meeting between CIA head William Burns and the director of the Russian Foreign Intelligence Service Sergei Naryshkin on 14 November. Most recently, Ankara tried to mediate a temporary ceasefire during Christmas according to the Julian Calendar observed by Orthodox Russians and Ukrainians (7 January). (https:// www.reuters.com/world/erdogan-tells-putin-ceasefire-needed- ukraine-peace-efforts-presidency-2023-01-05/).

21. Yuruk, B., ‘UN says 10 million tons of grain shipped in 3 months as it urges renewal of Ukraine deal’, Anadolu Agency, 3 November 202(https://www.aa.com.tr/en/world/un-says-10-million-tons-of-grain- shipped-in-3-months-as-it-urges-renewal-of-ukraine-deal/2728965).

22. The UN has been trying to negotiate a concession by Kyiv allowing Russian ammonia to be exported through a pipeline running from the Volga region to Odesa. Yet the Ukrainian authorities appear not to have opened the route at the moment. Faulconbridge, G. and Nichols, M., ‘UN trying to get Russian ammonia to world through Ukraine’, Reuters, 14 September 2022 (https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/ un-proposed-ammonia-deal-ukraine-would-stabilise-grain-deal- diplomat-2022-09-13/).

23. The impression was reaffirmed in September 2022 when Russia failed to stop another Azerbaijani offensive.

24. Zolyan, M., ‘How the West managed to sideline Russia in mediating the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict’, Carnegie Politika, 9 November 2022 (https://carnegieendowment.org/politika/88347).

25. Wesolowsky, T. ‘Blocking of key Nagorno-Karabakh artery triggers fresh tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan’, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 22 December 2022 (https://www.rferl.org/a/armenia-azerbain- karabakh-lachin-blockage/32189647.html).

26. ‘Azerbaijan rejects Armenia’s alternative options for Zangezur corridor deal’, Daily Sabah, 18 October 2022 (https://www.dailysabah.com/ politics/azerbaijan-rejects-armenias-alternative-options-for-zangezur- corridor-deal/news).

27. In October, the EU dispatched a monitoring mission along the Armenian- Azerbaijani border. The move came after talks between EU Council President Charles Michel and Emmanuel Macron, President of France, with Pashinyan and Aliyev on the margins of the EPC’s Prague Summit on 6 October. There was also a meeting between Macron, Erdoğan, Pashinyan, and Aliyev.

28. Euractiv, ‘Commission chief heads to Azerbaijan in search of more gas’, 18 July 2022 (https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/ commission-chief-heads-to-azerbaijan-in-search-of-more-gas/).

29. Kakhkachishvili, D., ‘Turkish company to replace demolished bridge in Irpin, Ukraine’, Anadolu Agency, 23 June 2022 (https://www.aa.com. tr/en/russia-ukraine-war/turkish-company-to-replace-demolished- bridge-in-irpin-ukraine/2620906); ‘Turkish builders say ready to play role in reconstruction of Ukraine,’ Daily Sabah, 19 August 2022 (https:// www.dailysabah.com/business/economy/turkish-builders-say-ready- to-play-role-in-reconstruction-of-ukraine).

30. He made this statement in May 2016, during the crisis in relationswith Moscow that followed the shooting down of a Russian plane in Syria. (https://eurasianet.org/erdogan-plea-nato-says-black-sea-has- become-russian-lake).