Early warning systems (EWS) are at the heart of conflict prevention strategies, particularly as a component of operational prevention.1 EWS support decision-makers with timely information, analysis and response options.2 Although the first generation of EWS have been around since the 1970s and 1980s, they did not come to prominence until the 1990s. In the aftermath of the war trauma in Somalia and the Mano River region (Liberia and Sierra Leone) and the 1994 Rwanda genocide, African EWS – in particular those of the Organisation of African Unity, its successor, the African Union (AU), and the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) – were developed to address threats to human security. These EWS have served as a strong foundation for early warning and early action (EWEA) in the continent. Many lessons have been learned in particular from West Africa’s experience, namely from the ECOWAS Early Warning and Response Network (ECOWARN), launched in 2003. ECOWARN has the capability to reform institutions from within the organisation and take grassroots perspectives into account, positioning it as the most advanced regional EWEA system in Africa.3

Creating the AU in 2002 marked a shift from non-intervention to non-indifference at the continental level. The African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) was an opportunity for African states to display strong political will to develop conflict prevention and resolution mechanisms, by establishing the Continental Early Warning System (CEWS) as one of the APSA’s five components. Over the years, multiple reinforcements have provided African institutions and member states with human, logistical and financial capacities to monitor, analyse and develop tailored and timely responses and policy options to address security challenges. Yet the EWEA gap, at both continental (CEWS) and regional (ECOWARN) levels, remains substantial and affects the full operationalisation of the prevention agenda. Why have political decision-makers not implemented those preventive tools adequately? How can closer relationships between regional and continental EWS in Africa bridge the EWEA gap?

To answer these questions, this Conflict Series Brief investigates the challenges and opportunities of cooperation between ECOWARN, the most sophisticated African regional EWEA system, and CEWS, a continental hub for data collection and analysis. It begins by analysing the impact of a lack of clear and systematic collaboration between regional and continental organisations on the development of the overall African EWS. While challenges remain in the institutional division of labour between the AU and ECOWAS, there has been progress in designing their EWS and implementing data collection and analysis. The second part of this Brief argues that the persistent EWEA gap lies in three main challenges on which CEWS and ECOWARN have focused their efforts: the lack of regular interaction between early warning (EW) officials and decision-makers, the unpredictability of conflict dynamics and the political dimensions of conflict responses. The Brief concludes by presenting some lessons learned for Africa’s prevention agenda.

Challenges and progress in AU-ECOWAS early warning cooperation

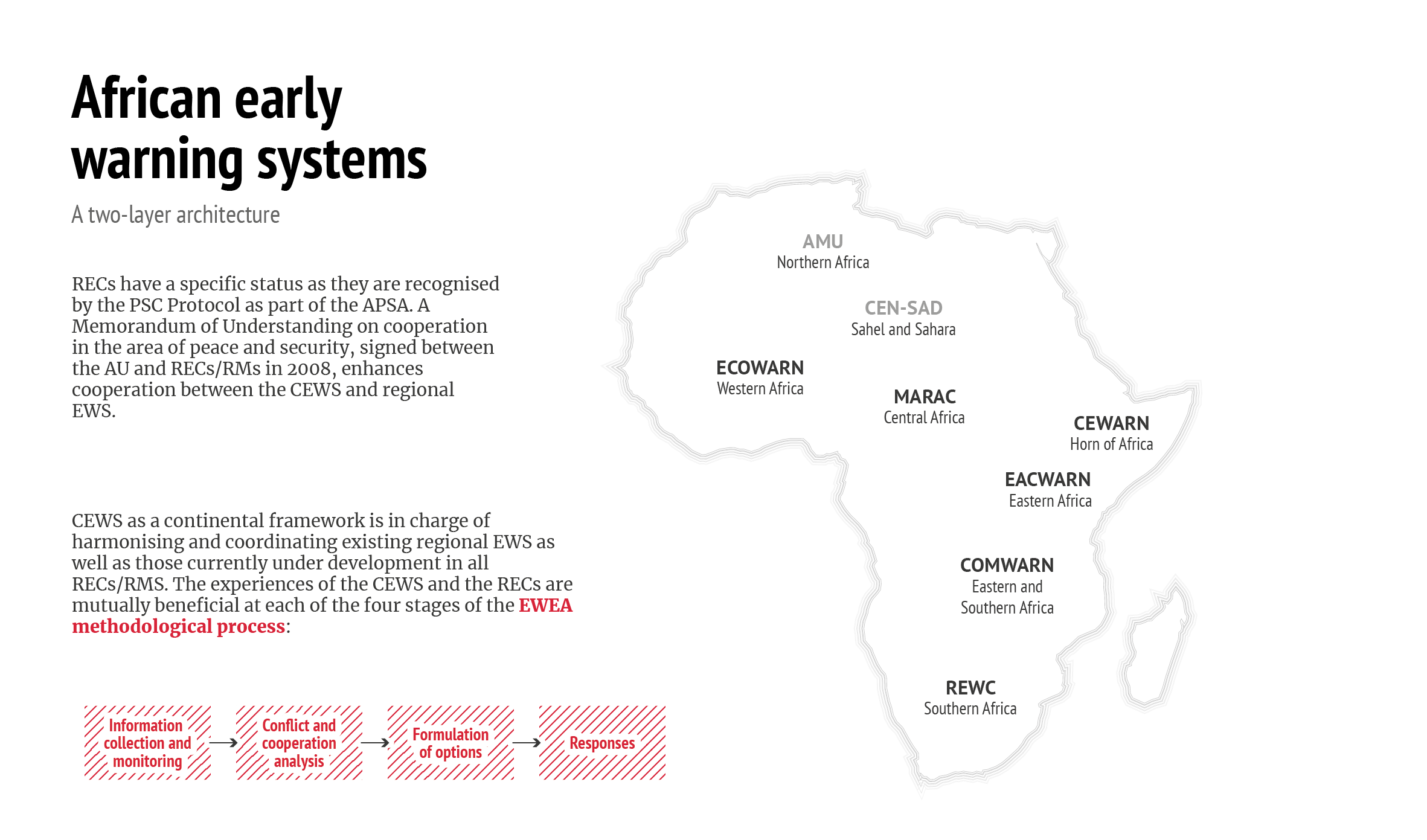

As articulated in the 2002 Protocol relating to the Establishment of the Peace and Security Council (PSC) of the AU, the APSA consists of several pillars with different roles to support the PSC, such as the Military Staff Committee, the African Standby Force, the Peace Fund, the CEWS and the Panel of the Wise, which has a preventive and mediatory role. Based on each of these pillars with an existing or potential role in conflict prevention, the AU, in collaboration with regional economic communities (RECs)/regional mechanisms (RMs), introduced a fully-fledged CEWS covering all aspects of violent conflict across the entire continent.

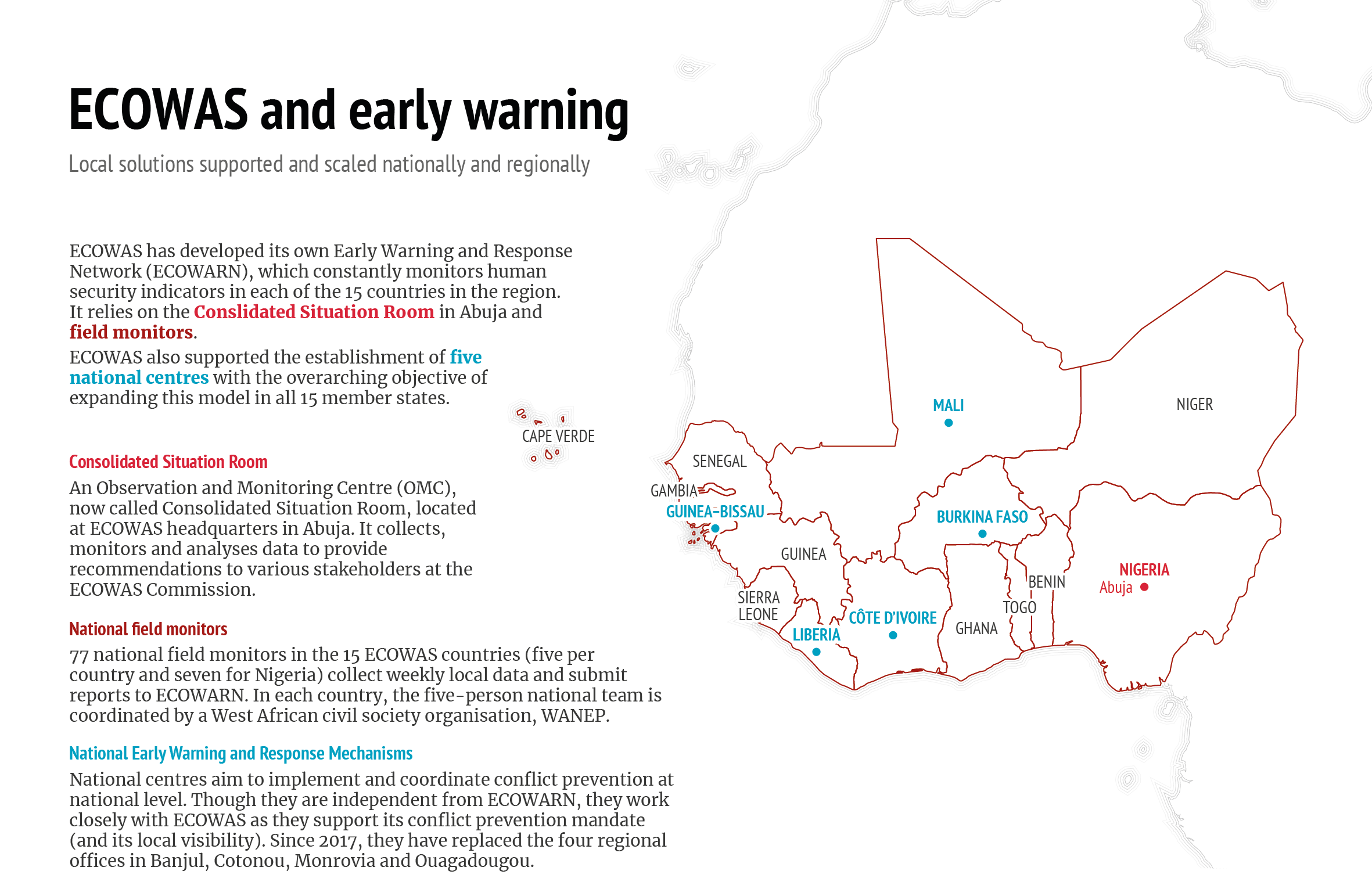

When analysing the efficiency of the APSA, division of labour between the AU and the RECs is central.4 Part of the complexity of the division of labour is due to historical heritage and debate; a much older ECOWAS feels the need to justify its legitimacy in the context of the established AU. When the APSA was created, ECOWAS, founded in 1975, had already developed well-established mechanisms for conflict analysis and prevention. Like some other RECs, ECOWAS faced regional security issues in the 1990s, and ECOWARN resulted from the political, economic and social challenges confronting West African states then. Since the adoption of the 1999 Protocol on the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peacekeeping and Security,5 ECOWAS has striven to build trust among its member states on the prevention agenda, strongly supported by countries that have experienced war in the recent past (Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia and Sierra Leone).6 Hence, for ECOWAS, the AU’s efforts to lead conflict prevention in Africa overlook ECOWARN’s proven value and legitimacy in the region.

The African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA) was an opportunity for African states to display strong political will to develop conflict prevention and resolution mechanisms.

The second main explanation for the lack of clarity in the division of labour is the many texts that define and set out the role of the RECs but do not present an agreed joint definition of strategies for supplying EWS data. The AU Constitutive Act underlines the need to coordinate and harmonise policies between existing and future RECs. To take their experience into account, the 2002 PSC Protocol7 lists a specific role for RECs/RMs in the implementation of the CEWS: collecting, processing and transmitting data to the observation and monitoring centre – the Situation Room – at the AU Peace and Security Department.8 The 2008 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on Cooperation in the Area of Peace and Security between the AU, RECs and the Coordinating Mechanisms of the Regional Stand-by Brigades of Eastern and Northern Africa9 goes one step further in referring to subsidiarity, comparative advantage and complementarity. In spite of these principles in formal AU texts, they lack definition and allow for discretion in interpretation by different parties.10 The interplay between the AU and other RECs varies widely because of the RECs’ different organisational capacities and preparedness. The overlapping state membership also has implications for the choice of RECs to respond to conflict11 and for the AU’s capacity to deal with the risk of conflicting responses. The national interests of neighbouring states are another issue in the division of labour and the responsibility of the AU or a REC to respond. Subsidiarity works well in West Africa thanks to ECOWAS’s capable institutions, recognition of its comparative advantage over other organisations and its member states’ political will to prevent and contain intrastate conflicts.

The challenge of harmonisation and coordination between the AU and ECOWAS makes cooperation unsystematic: notably, ECOWARN is not directly linked to the Situation Room in Addis Ababa. The practice has also been characterised by overlapping conflict prevention activities emphasised by institutional imitation as both EWS have the same functionalities. Moreover, the competition to prove their relevance and legitimacy risks harming the consistency of EW reports, products and outcomes. However, considerable progress has been made in the last decade to enhance technical cooperation between CEWS and ECOWARN.

Given its mandate to liaise with other institutions, CEWS is considered a continental hub for collection and exchange of open-source information. It aims to facilitate anticipation and prevention of conflicts in all AU member states. It comprises (i) the Situation Room and (ii) observation and monitoring centres at RECs.12 On the other hand, thanks to its geographical proximity and experience, ECOWARN enjoys a comparative advantage in knowledge, access and analysis of national and local information. It has developed cooperative efforts at international, regional, national and local levels and its transparent nature provides a check and balance on the orientation of the analysis, ensuring buy-in from member states. Over time, the mechanism has been able to collect national data with the collaboration of civil society and the support of governments.

To increase the efficiency of the overall African EWS, developing interoperability with regional components is a priority for CEWS.13 Collaboration started with periodic consultations with the RECs, including ECOWAS, during the drafting of the CEWS Roadmap.14 Technical capacity has significantly improved (technical quarterly meetings, joint briefings, technical support missions, experience sharing)15 thanks to recognition of the need to raise individual national efforts to prevent complex conflict situations. Despite the lack of a specific cooperation framework between CEWS and ECOWARN, their shared experiences benefit each of the four stages of the EWEA methodological process (data collection, analysis, policy options, response).

For information collection and monitoring, the AU and the RECs have signed an agreement for sharing data and analysis tools. CEWS also manages a set of indicators to which ECOWARN may contribute,16 with the objective of supporting the setting of common standards while encouraging a region-specific in-depth analysis. Both EWS use them for their own information collection and monitoring activities in the field. For interactive conflict and cooperation analysis, regular exchanges of information take place via the CEWS portal or by video-conference, enhancing personal relations between CEWS and ECOWARN staff.

To formulate policy and response options, CEWS and ECOWARN produce joint reports where possible.17 Coordination is institutionalised through regular AU/ RECs technical meetings where EW staff meet twice a year to discuss, review and share tools and technology. Joint training on strategic conflict assessments is also an opportunity to enhance staff capacities and discuss the relevance of indicators. Staff exchange visits and technical support programmes have also been carried out.

Although the relationship between the AU and ECOWAS is still very competitive, ECOWARN and CEWS have succeeded in becoming operational preventive tools by implementing their EW component (data collection and analysis, policy response). Yet, owing to persistent institutional and political challenges to the transformation of their recommendations into early action, they are still not adequately implemented or fully used to serve a consistent African conflict prevention agenda: a primary objective in improving the APSA’s effectiveness.

Data: Natural Earth, 2021

Challenges and priorities in bridging the EWEA gap

Despite the technical progress in collaboration, challenges in moving from EW to early action remain. Three issues in particular challenge the EWS and are tackled by both ECOWARN and CEWS: interaction between EW actors and decision-makers, collaboration to address transregional conflict, and translating state ambition for conflict prevention into practice.

Reconciling the interests of early warning officials and decision-makers

Globally, a principal EWEA disjuncture relates to a persistent cultural gap between EW officials, who operate on the levels of administration and implementation, and political decision-makers, who decide on action in response to EW reports.18 EWEA systems have a distinctive organisational culture, functions and dynamics, involving multiple stakeholders. This easily prevents a two-way flow of information, ideas and assessment to improve the system.

The priority for CEWS is to support the PSC’s mandate in conflict prevention and, thus, to present itself as a tool to reinforce state sovereignty rather than threaten it.

There are three main reasons that can explain this cultural gap. First, decision-makers tend to rely on trusted confidants and channels, including diplomatic sources or intelligence. While it is not considered a real substitute for CEWS products, the Committee of Intelligence and Security Services of Africa also produces reports at the AU level. EW products therefore become a secondary consideration to decision-makers, and their distinct value is underappreciated.19 Second, some conflict-related EW information might be classified, and early action deliberations are politically sensitive. In this case, there is a disconnect between EW, which requires open discussion, and early action, when decision-makers insist on compartmentalising and withholding information. Third, in a context of information overload and ongoing crises, preventing potential crises that might never escalate into large-scale violence is not a priority among decision-makers. Owing to this disconnect, they often cite a lack of useful EW information and describe recommendations they receive as generic. EW officials, meanwhile, seek to present timely information that is as accurate, credible and relevant as possible, but receive no feedback to tailor analyses.

To ensure a more efficient and informal flow of information, the AU and ECOWAS have both reduced the number of information channels. Therefore, the ECOWAS Early Warning Directorate was relocated from the department of Political Affairs, Peace and Security to the office of the Vice President of the Commission in 2018. This increases legitimacy and ensures a multidimensional (social, economic, health, etc.) rather than purely political approach.20 At the AU, a CEWS report goes through three tiers, from the Unit Head to the Head of the Conflict Prevention and Early Warning Division and, finally, the Commissioner for Peace and Security. This process is sometimes shortened when reports go directly to the Division Head and the Commissioner,21 but they rarely reach the PSC, the political decision-making organ. To enhance opportunities for direct interaction, informal breakfast meetings of the Commissioner for Peace and Security with PSC members, as well as horizon-scanning briefings to the PSC and others, have been instituted.22

One of the biggest challenges is the lack of feedback from decision-makers to EW officials to improve the quality, frequency and timeliness of their reports. Officials require detailed and clear feedback on tailoring their outputs to fine-tune final EW products and make sure they meet the principal users’ expectations.23 There is still room to improve understanding of what CEWS and ECOWARN do and how they produce their reports. Some AU member states regularly raise concerns about CEWS tools, considering them too theoretical or unrealistic.24 To address this, CEWS has considered a consultation to clear up some misunderstandings about the system and to commit itself to refining its EW tools.25 The priority for CEWS is to support the PSC’s mandate in conflict prevention and, thus, to present itself as a tool to reinforce state sovereignty rather than threaten it.26 ECOWAS has sought to embed transparency in EWS since the beginning. In the early stages, the regional organisation adopted a participatory approach to select indicators to monitor rising tensions. ECOWARN staff regularly brief their members and raise alerts as necessary, and member states reportedly often seek ECOWAS advice on internal security matters.27 Beyond these technical aspects, both CEWS and ECOWARN have to deal with transnational African conflict.

Addressing unpredictability of transnational conflicts

Frequently, armed and unarmed conflicts spill across state borders. In the 1990s, Liberia, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Somalia showed that most countries are part of the regional conflict system; their security cannot be understood in isolation from other states. Despite investments in financial, human and technical capacities at CEWS and ECOWARN, it is challenging to predict the nature of conflict without assessing national structural vulnerabilities. Many threats to peace are regional and need to be addressed in a coordinated (national and local) way.28 Recent conflicts in the Lake Chad Basin and the Sahel resulted from interaction between situational and structural, local and national vulnerabilities (political, economic, social, health, environmental). Although the AU and ECOWAS have developed sophisticated EWS, finding appropriate resources for early action remains challenging because conflicts change rapidly and have transregional dynamics. The AU and ECOWAS acknowledge that conflict prevention must focus both on intervening before large-scale violence occurs and on the root causes of conflict, such as the absence or failure of state response to deliver public services and meet populations’ expectations of equal access to justice, redistribution of national resources and protection. They have developed joint mechanisms and tools to enhance structural conflict prevention efforts. As the Covid-19 health crisis has shown, no state is immune, and structural vulnerability assessment is a collective responsibility.

ECOWAS has a comparative advantage due to its proximity to African CSOs and the ongoing decentralisation of its EWEA to national centres.

At the request of member states, the AU Commission has developed a Continental Structural Conflict Prevention Framework, which the PSC endorsed in 2015.29 It aims to strengthen the AU’s direct prevention actions with activities to assist volunteer states in identifying their structural vulnerability to conflict at an early stage and developing country structural vulnerability mitigation strategies. In 2016, a Technical Working Group on Structural Conflict Prevention was constituted by CEWS, all the EWS of the RECs, the African Development Bank and the African Peer Review Mechanism, to exchange lessons learned and best practices. In October 2017, Ghana became the first African country to voluntarily embark on this process, with joint support from the AU and ECOWAS. Its country structural vulnerability assessment report was presented in October 2018. The AU and ECOWAS support volunteer member states to establish and operationalise national EW mechanisms and national peace institutions. The AU has also provided technical support to governments to establish situation rooms.

Since 2017, ECOWAS has, under the authority of member states, supported the creation of five National Coordination Centres for Early Warning and Early Response Mechanisms in Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia and Mali.30 These centres are strategically placed within national institutions to implement and coordinate conflict prevention at national level. African civil society organisations (CSOs) are integral to the conflict prevention agenda, as conflicts’ local roots also require local solutions supported and scaled nationally and regionally. In partnership with national authorities, CSOs and local communities can be primary local peace actors in low-intensity conflicts. Here, CEWS faces limitations, as it sometimes lacks local information for want of staff, an AU field mission or reporting from local mechanisms.31 To be coherent and effective, conflict analysis must be regional and continental, while solutions must be nationally driven and supported by local initiatives.32 To strengthen its position on the local dimension, in November 2019, the AU added prevention, management and settlement of local conflicts to its agenda in the Bamako Declaration.33

ECOWAS has a comparative advantage due to its proximity to African CSOs and the ongoing decentralisation of its EWEA to national centres. It can use this to act as a sensor for CEWS and to address CEWS’ missing local links.34 In ECOWAS, methods for EWEA to deal with local conflict have been effectively in use since 2002 on the basis of the MoU between ECOWAS and the West African Network for Peacebuilding (WANEP) on information gathering and analysis, and the implementation of ECOWARN. In 2018, the initiative was replicated at continental level, with WANEP deploying two staff at the AU to develop CEWS’s capacity to engage civil society field monitors and support the expansion of this model in other RECs/RMs.35 However, unlike at ECOWAS, AU member states are divided about the use of civil society-based information, implying deeper domestic considerations and political realities.

Turning the state conflict prevention agenda into practice in African institutions

For both AU and ECOWAS, the transition from analysis to response remains a challenge, as illustrated by the gap between the implementation regional/continental mechanisms and national priority agendas. Efficient EWEA requires substantive commitment from national decision-makers. Preventive action is a political rather than a technical endeavour. Even if analysis and recommendations are based solidly on data, political representatives rarely consider them neutral. It is almost a reflex for political decision-makers to question the methodology and assumptions upon which the analysis was based, and to consider it political interference.

Even though the institutionalisation and professionalisation of EWS have interested member states in using conflict prevention tools, national interests and sovereignty dominate the prevention agenda.36 In every situation, categorising conflicts is a sensitive issue. As there is sometimes a fine line between maintaining public order and peacekeeping, political leaders fear losing control of the situation by internationalising it.37 While some countries, such as Ghana, push for more transparency on states’ vulnerabilities and their implications, and value preventive collective action,38 many states invoke sovereignty to avoid international scrutiny of the potential causes of crises, as many of them feel uncomfortable discussing their structural vulnerabilities openly.39 Cameroon’s conflict risks were never treated as a matter of concern because of the political implications of putting them on the PSC’s agenda.40 At both the AU and ECOWAS, there is persistent tension between countries over their leaders’ different perceptions of EWS analyses. While some of them take into account the risk that their national fragilities may trigger violence, others prefer to emphasise the state’s capacity to exercise its powers and maintain order. Moreover, developing data collection methodology is sometimes a technical and political challenge given the lack of well-established channels between member states to share data, and mistrust about the final use of the data. Some state representatives remain reluctant to share certain sensitive data with other countries, lest it undermine their national security.

Finally, some governments’ lack of confidence in the EW tools is increased by the confusion between EW and intelligence. Much of EWS is based on unclassified information and is not intended to replicate national intelligence services.41 They use open-source material and aim to serve human security, not regime interests. In recent years, seeking better equipment and efficiency, EWEA stakeholders have talked about insufficient field data from open sources and the need to combine them with other sources of classified information. Final users of EWs are usually a few privileged people. There is, however, a development to make EWS strictly open source to embrace as much information as possible. CEWS and ECOWARN would be wise to clarify their position on this, as their methodologies could be questioned otherwise.42 Here again, ECOWAS has the comparative advantage of solidarity among member states, which is a key success factor.

Conclusion

Although many regional and international forums have reaffirmed conflict prevention as a priority, in practice it still takes second place. Stakeholders are “more sensitive to open crisis than to crisis signals and indicators”,43 not only in Africa. ECOWARN and CEWS are efficient but, as it stands, they are limited by the willingness of Heads of State to decide on concrete preventive action. The main difficulty is the ability of decision-makers to intervene without hitting the barrier of sovereignty and having to pay a political price for their audacity. Three lessons can be learned from institutional and political challenges. Most of them are also relevant to other regional conflict prevention organisations.

First, the real effects of EWS on conflict prevention are still difficult to assess, value and optimise in the long term. The multiplication of sources and the complexity of conflict situations have increased the demand for human and technological capacity. Efficient EWS require not only sufficient data but adequate data quality and effective interaction between EW officials and decision-makers. Even though developing the necessary technical expertise is an absolute prerequisite, it is critical that any early response system include mechanisms for reviews and provide feedback to improve EWS, especially when they proceed ad hoc. Having said that, the priority given to technical responses, financial support and capacity-building activities should not ignore the political environment.

As the competitive AU-ECOWAS relationship illustrates, behind technical questions lie political issues.

Second, as the competitive AU-ECOWAS relationship illustrates, behind technical questions lie political issues. National and regional stakeholders strive for visibility and credibility to benefit from external financial, human and financial support. When conflict prevention actors aim primarily to promote their own interests and agenda, the lack of coordination is detrimental to the implementation of consistent and long-term conflict prevention policies. For instance, many training offers for staff capacity-building do not meet a real need – a striking example of duplicated efforts with a short-term perspective. Improving technical capacities alone cannot change the current situation.

Third, like military interventions, conflict response depends as much on capacity-building as on interpersonal relationships of the early action decision-makers. Beyond mistrust in sharing EWS data sources, the need for political leaders to appear to be in control cannot be underestimated in a context where African political leaders’ legitimacy and sovereignty are challenged. The root causes of most conflicts in Africa are long-term local and national structural vulnerabilities. Frequently, African leaders are said to lack political will for effective implementation of EWEA. But we need to understand how much African leaders share a collective evaluation of human security challenges, are willing to negotiate on sovereignty to protect others from spillover impacts, and have sufficient political room for manoeuvre to implement regional mechanisms at national level.

In order to overcome the lack of political stakeholders’ commitment, two options are worth considering, to sidestep institutional constraints by using the wide range of other African tools.

First, greater involvement of civil society in regional and continental conflict prevention mechanisms can circumvent challenges related to political constraints and build trust with the local stakeholders.44 Civil society becoming more active would make decision-making less cumbersome, and CSOs could advocate better for populations’ expectations.

Second, the decision-making process remains concentrated at the level of the AU or ECOWAS Commission, given that high-level authorities deal directly with the Heads of State. While early action in individual states has often resulted from their separate political decision-making, there is a wide range of other tools to respond collectively and collaboratively to regional or continental alerts. The AU and RECs have lately taken concrete steps towards strengthening their relations and enhancing their capacity to collectively develop other practices in conflict prevention. These efforts have taken the form of joint missions conducted under the Pan-African Network of the Wise, launched in 2013 as part of the APSA. EW actors have no choice but to constantly and cleverly adapt their resources and tools to provide decision-makers with more room for action. Conflict prevention has often been ad hoc and continues to depend on the capacity to mobilise the required coalition of states for each preventive intervention.

References

1. Operational prevention refers to “measures applicable in the face of imminent crisis” while structural prevention means “measures to ensure that crises do not arise in the first place or, if they do, that they do not re-occur”; ECOWAS Commission, ECOWAS Conflict Prevention Framework regulation MSC/REG. 1/01/08, Abuja, January 2008, p. 13. For the African Union, operational prevention relates to actions designed to address the proximate or immediate causes of conflicts, normally taken during the escalation phase of a given conflict, where proximate, dynamic factors come into play: African Union, Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the Follow-up to the Peace and Security Council Communiqué of 27 October 2014 on Structural Conflict Prevention PSC/PR/2(D), April 29, 2015, www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-502- cews-rpt-29-4-2015.pdf.

2. For a definition of early warning, see Alex Schmid, Thesaurus and Glossary of Early Warning and Conflict Prevention Terms, PIOOM Synthesis Foundation, abridged version edited by Sanam B. Anderlini for FEWER (Erasmus University), May 1998.

3. See Amandine Gnanguênon, “Afrique de l’Ouest: faire de la prévention des conflits la règle et non l’exception,” Observatoire Boutros-Ghali du maintien de la paix, September 2018, https://www.observatoire-boutros-ghali.org/publications/afrique-de-l%E2%80%99ouest-faire-de-la-pr%C3%A9vention- des-conflits-la-r%C3%A8gle-et-non-l%E2%80%99exception.

4. African Union Commission, Peace and Security Department, African Peace and Security Architecture: APSA Roadmap (2016-2020), Addis Ababa, December 2015, http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/2015-en-apsa-roadmap-final.pdf.

5. ECOWAS, Protocol relating to the Mechanism for Conflict Prevention, Management, Resolution, Peacekeeping and Security, Lomé, December 10, 1999..

6. Paige Arthur and Céline Monnier, Creating the Political Space for Prevention: How ECOWAS Supports Nationally Led Strategies, Center on International Cooperation, August 2019, p. 5, https://cic.nyu.edu/publications/Creating-the- Political-Space-for-Prevention-How-ECOWAS-Supports-Nationally-Led- Strategies.

7. African Union, Protocol relating to the establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union, Addis Ababa, 2003, www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc- protocol-en.pdf.

8. El-Ghassim Wane et al., “The Continental Early Warning System Methodology and Approach,” in Ulf Engel and Joao Gomes Porto (eds), Africa’s New Peace and Security Architecture: Promoting Norms, Institutionalizing Solutions (Farnham: Ashgate, 2000), pp. 91-110.

9. Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the Area of Peace and Security between the African Union, the Regional Economic Communities and the Coordinating Mechanisms of the Regional Standby Brigades of Eastern and Northern Africa, Addis Ababa, June 2008, https://www.peaceau.org/uploads/ mou-au-rec-eng.pdf.

10. Amandine Gnanguênon, A Cooperation of Variable Geometry: The African Union and Regional Economic Communities, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Africa Department, August 2019, http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/iez/15632.pdf.

11. Amandine Gnanguênon, “Mapping African Regional Cooperation: How to Navigate Africa’s Institutional Landscape,” Policy Brief, European Council on Foreign Relations, October 29, 2020, https://ecfr.eu/publication/mapping- african-regional-cooperation-how-to-navigate-africas-institutional- landscape.

12. Op.Cit., Protocol relating to the establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union.

13. See African Union, African Union Continental Early Warning System: The CEWS Handbook, 7th draft, February 2008, http://www.peaceau.org/uploads/cews- handook-en.pdf.

14. See African Union, Roadmap for the Operationalization of the Continental Early Warning System, draft, July 2005, https://archives.au.int/bitstream/ handle/123456789/8319/DRA-ROA-CEW_E.pdf?sequence=8&isAllowed=y

15. Op. Cit., African Peace and Security Architecture, p. 25.

16. Interview with CEWS analyst, Addis Ababa, December 5, 2019.

17. Interview with CEWS analyst, Addis Ababa, December 6, 2019.

18. Laurie Nathan, “Africa’s Early Warning System: An Emperor with No Clothes?,” South African Journal of International Affairs, vol. 14, no. 1 (2007), pp. 49-60.

19. Interview with ECOWAS official, Abuja, June 2018.

20. Interview with ECOWAS official, Abuja, June 2018.

21. Yann Bedzigui, “Preventing Conflict: How to Make the AU’s Policy Work,” ISS Africa Report, no. 11, July 2018, https://issafrica.org/research/africa-report/ preventing-conflict-how-to-make-the-aus-policy-work.

22. Ibid.

23. Op. Cit., “Africa’s Early Warning System”.

24. Ibid.

25. Interview with CEWS analyst, Addis Ababa, December 6, 2019.

26. Interview with CEWS analyst, Addis Ababa, December 6, 2019.

27. Op. Cit., Creating the Political Space for Prevention.

28. See “Africa’s Early Warning System,” Op. Cit., p. 56

29. Conflict Prevention and Early Warning Division (CPEWD), “Continental Early Warning System (CEWS),” presentation, Addis Ababa, December 2019.

30. Op. Cit., “Afrique de l’Ouest”.

31. Ulf Engel, “Knowledge Production on Conflict Early Warning at the African Union,” South African Journal of International Affairs, vol. 25, no. 1 (2018), pp. 117- 32.

32. Interview with CEWS analyst, Addis Ababa, December 6, 2019.

33. “Déclaration de Bamako sur l’accès aux ressources naturelles et conflits entre les Communautés,” Le Nouvel Afrik.com, December 3, 2019, https://www. afrik.com/declaration-de-bamako-sur-l-acces-aux-ressources-naturelles-et-conflits-entre-les-communautes.

34. Interview with CEWS analyst, Addis Ababa, December 6, 2019.

35. Interview with WANEP representative, Addis Ababa, December 5, 2019.

36. See, for CEWS, “Knowledge Production on Conflict Early Warning at the African Union,” Op. Cit.

37. Interview with AU official, Addis Ababa, December 5, 2019.

38. For the AU, see Martin Welz, “A ‘Culture of Conservatism’: How and Why the African Union Member States Obstruct the Deepening of the Integration,” Strategic Review for Southern Africa, vol. 36, no. 1 (2014), pp. 4-24.

39. Op. Cit., “Preventing Conflict”.

40. See Institute for Security Studies, “Why the PSC Should Discuss Cameroon,” PSC Report, April 25, 2019, https://issafrica.org/pscreport/psc-insights/why- the-psc-should-discuss-cameroon.

41. See Jakkie Cilliers, “Towards a Continental Early Warning System for Africa,” ISS Paper, no. 102, April 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/99193/PAPER102. pdf.

42. Interview with CEWS analyst, Addis Ababa, December 6, 2019.

43. Interview with civil society representative, Lomé, March 2018.

44. Ibid.