You are here

Fog in Channel? The impact of Brexit on EU and UK foreign affairs

Introduction

The UK’s rejection of any institutionalised relationship with the EU in foreign, security and defence policy (FSDP) is arguably the most noteworthy feature of the post-Brexit dispensation. In a stark reversal in early 2020, the British government abandoned pledges made in the 2019 Political Declaration to ‘establish structured consultation and regular thematic dialogues [that] could contribute to the attainment of common objectives’, including on the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) (1). This gap was intensified by the absence of any reference to foreign affairs in the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) or the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (IR) (2). Indeed, the IR essentially ignores the EU, referring only to British ambitions to remain a lead European defence actor, with a focus on multilateral venues (notably the UN and NATO), bilateral relations and ad hoc groupings. In short, an EU-sized hole now exists in British foreign policy thinking.

This matters in London and across Europe. While in the EU, the UK exercised significant influence and leadership in FSDP, its EU membership magnifying its global capacities. In leaving, Sir Simon Fraser, formerly permanent under-secretary in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), warned that Brexit represented ‘the biggest shock to [the UK’s] method of international influencing and the biggest structural change to our place in the world since the end of World War Two’ (3). From the EU’s perspective, as observed by High Representative Josep Borrell, ‘with Brexit, nothing gets easier and a lot gets more complicated. How much more complicated depends on the choices that both sides will make’ (4). The choices thus far indicate a rejection of ‘old obligations’ (5) and an essentially transactional relationship that will be ‘structurally adversarial for the foreseeable future’ (6).

Nonetheless, Brexit also gives both the UK and the EU a once-in-a-generation opportunity to rethink and reconfigure their approaches to foreign affairs and how they navigate a profoundly changed regional context. To understand the scale of this undertaking, we offer an innovative thematic analysis focused on four ‘Rs’: reputation, responsibility, resources and relevance. Each ‘R’ represents a core element of both sides’ respective foreign policies, offering insights into possible international roles and goals. The four ‘Rs’ also help us identify the main risks and opportunities Brexit encompasses, providing a conceptual symmetry as to how the choices of both the EU and UK might align and impact each other.

UK post-Brexit options

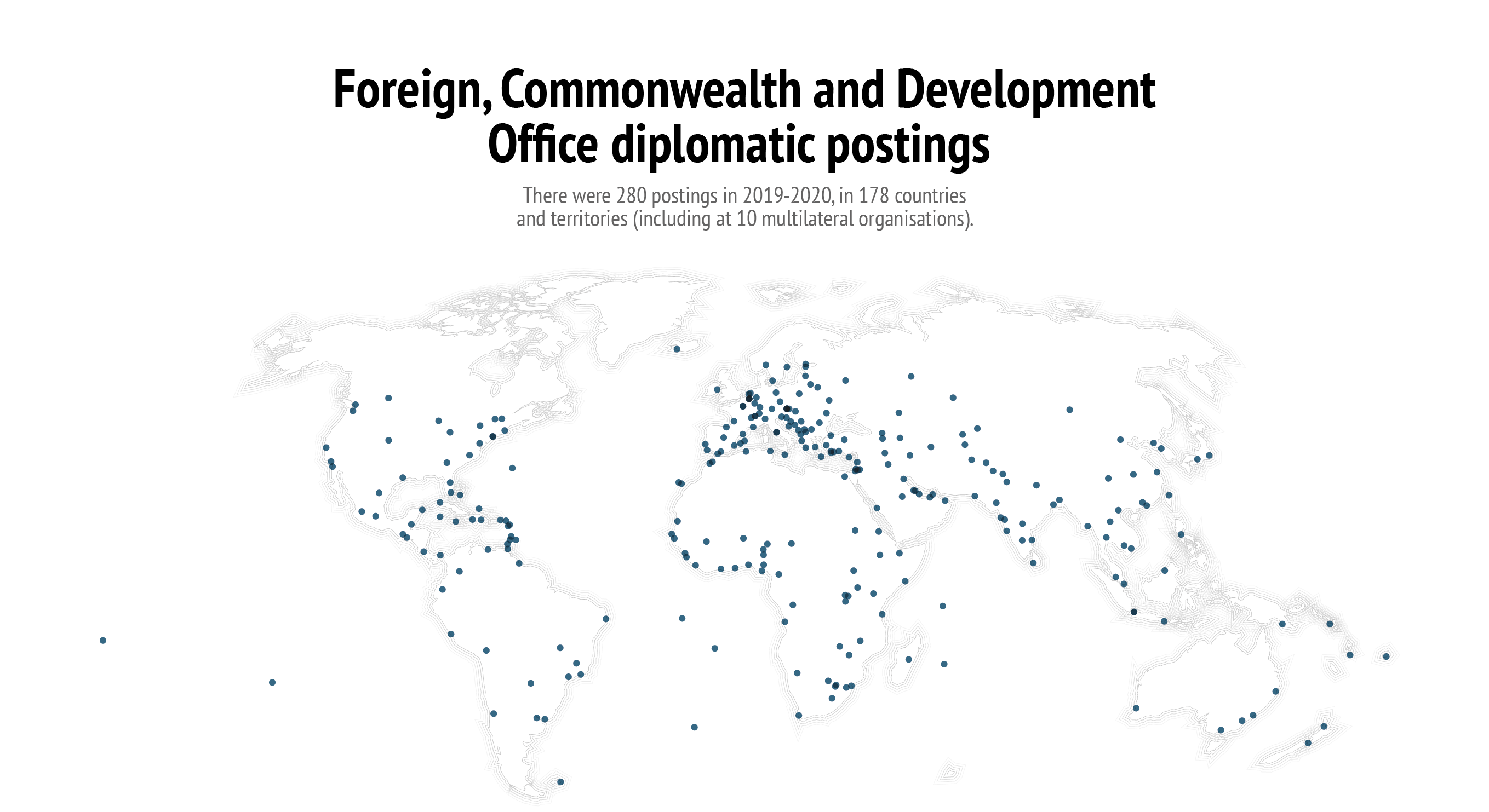

For Britain, Brexit in FSDP began immediately after the referendum. It was increasingly semi-detached from CFSP prior to January 2020 and although Boris Johnson promised subsequently that the UK ‘will always cooperate with our European friends […] whenever our interests converge’ (7), hopes this would involve an institutionalised relationship with the EU in FSDP disappeared once the UK revealed its limited ambitions for the TCA. For Johnson’s government, Brexit means looking beyond Europe. Indeed, at times it seems driven by a desire to erase the experience of EU membership altogether. Instead, the focus is on making real ‘Global Britain’. The 2021 IR seeks to add genuine substance to what, for so long, was just a slogan. However, it was largely pre-empted by key decisions in 2020, including merging the FCO and Department for International Development (DfID) to form the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) (8), significantly increasing defence spending (9) and reducing (apparently temporarily) overseas aid to 0.5 % of GDP from the 0.7 % international commitment (10). Despite this, the direction of travel is clear: the foundations of post-Brexit UK FSDP include the transatlantic security relationship; prioritising the Indo-Pacific region for future trade and commerce; greater investment in nuclear deterrence; and an ‘unequivocal’ commitment to European security (11).

For all its positives, the absence in the IR of any serious thinking about how the UK should engage with the EU remains a significant shortcoming. UK strategy is to compartmentalise the EU as a trade and economic partner only, minimising its importance in FSDP. The preference instead is for bilateral cooperation or the use of other formal or ad hoc contexts. The feasibility of this approach is highly questionable: on key foreign policy questions, it is simply unrealistic to believe EU member states will abandon the CFSP and its structures. The risk for the UK, therefore, is that as it tries to set out a positive and proactive post-Brexit FSDP agenda, its blind spot vis-à-vis the EU will limit its capacity to achieve its objectives.

Challenges and opportunities

Reputation

Brexit has damaged the UK’s reputation for domestic stability and pragmatic international engagement. It has long considered itself a multilateralist, globally-networked power, helping construct and championing the international rules-based system, transatlantic security, and latterly European integration. Brexit represents a rejection of a key component of this multilateralism. Combined with the domestic upheaval the implementation of the decision has entailed, this has left the UK looking introverted and disengaged, continuing a trend that predates the referendum.

Specific Brexit-related policy choices have also undermined the UK’s reputation as a reliable and trustworthy partner, particularly in Northern Ireland. In 2020, the Johnson government threatened to abrogate key elements of the Northern Ireland Protocol, part of the Withdrawal Agreement negotiated just months before, and thereby break international law, albeit ‘in a specific and limited way’ (12). Roundly criticised by the House of Lords for ‘undermin[ing] the rule of law and damag[ing] the reputation’ of the UK (13), it was also viewed with deep concern overseas, particularly in the US (14). In early 2021, unilateral British decisions over the Protocol’s implementation contributed to a further crisis in UK-EU relations, resulting in the European Commission initiating infringement proceedings (15). This concerning pattern of behaviour — whereby the UK ignores treaty obligations when politically expedient — indicates the government has failed to fully internalise the nature of its changed relationship with the EU.

The IR addresses some of the reputational concerns. Highlighting areas where the UK can potentially focus its considerable expertise, influence and leadership capabilities, the IR presents a determined statement of British international re-engagement. However, statements about playing a positive international role need to be matched by resources and action (16). An antagonistic relationship with the EU — whose support is essential for the UK-hosted COP26 to succeed — will weaken the UK’s leadership claims, and any uncertainty over its fulfilment of treaty obligations will be corrosive to its reputation in the longer term.

Responsibility

Responsibility is central to the UK’s international role conception, based on a strong multilateral vocation and support for the international rules-based system. It has benefited greatly from positions of institutionalised leadership — e.g. the UN Security Council and NATO — which magnify its power, enabling it to ‘punch above its weight’, despite its relative decline compared to new and re-emerging powers.

The UK has a clear interest in safeguarding the integrity of the multilateral system and ensuring all major powers remain invested in its maintenance. It has proven adept at exercising diplomatic influence in international organisations, with ambitions to act as a global broker of international agreements. However, the example it sets matters. The implementation of Brexit — especially the aforementioned willingness to break international agreements — signals that its belief in this system is now more contingent. This risks undermining both the system itself and the UK’s capacity to play a credible leadership role.

To be considered a responsible power, Britain must pursue an activist, internationalist foreign policy.

To be considered a responsible power, Britain must pursue an activist, internationalist foreign policy. It has been a staunch advocate for the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreement with Iran, reaffirmed its support for Security Council reform and expansion, increasing its UN profile by contributing 300 soldiers to the Mali peacekeeping mission. It is currently pushing to expand the G7’s reach in Asia (17), is advocating a so-called ‘D10’ of leading democratic states to challenge authoritarian powers and has vocally challenged China over its actions in Hong Kong (18).

These actions however are undermined by the decision to end UK spending commitments, such as reducing overseas aid to 0.5 % of GDP, an area where formerly it could boast of genuine global impact. Strongly criticised domestically and internationally, the decision is regarded by many, including former Conservative International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell, as ‘a strategic mistake with deadly consequences’ (19). It also undermines ambition that the UK be ‘a force for good’ (20) and signals further British disengagement (21). More pragmatically, it is a false economy: weakening further already fragile regions will potentially necessitate future more costly and larger-scale interventions, e.g. in Yemen.

Resources

The resources the UK is willing and able to commit are crucial to its post-Brexit FSDP aspirations and signal internationally how seriously these should be taken.

Defence - The IR reiterated the government’s 2020 commitment to increase defence spending by an additional £16.5 billion over four years, the largest boost since the end of the Cold War. On paper, this secures the UK’s position as NATO’s second-largest defence spender while expanding the nuclear deterrent underlines its determination to remain the alliance’s ‘leading European ally’ (22). These increases cannot hide major reductions in manpower and capabilities over the last two decades, however (23). Although personnel numbers are a crude measure, it is notable that UK armed forces have shrunk from approximately 204 000 in 2000 to just over 145 000 currently (24). The British Army, meanwhile, will see its trained personnel reduced to 72 500 by 2025 (25), its smallest number in 300 years. A leaked Ministry of Defence report recently indicated the UK faces a shortage of battle-ready soldiers and Tobias Ellwood, chair of the Commons Defence Select Committee, warned that ‘Britain’s role on the world stage is at stake and our relationship with the US’ (26). The UK’s commitment as a military partner and ally may not be in question but a significant capabilities-expectations gap may emerge which greater investment in drones and nuclear capacities cannot prevent.

Diplomacy - The FCO/FCDO and Diplomatic Service have faced severe budgetary constraints over the same period (27). Year-on-year, investment declined significantly under Conservative and Labour Governments in the 1990s and 2000s, with bigger cuts by the Coalition (2010-15). In 2015-16, for example, the UK spent less per head on diplomacy than the US, France, Germany, Australia, Canada and New Zealand (28). Some see the FCO-DfID merger as an opportunity for the sizeable aid budget to be reallocated to broader diplomatic tasks. The Treasury is also looking at it as a source of post-Covid savings. These are not risk-free choices. Their impact will be felt by some of the world’s weakest and most vulnerable communities. They also risk signalling retrenchment and disengagement, while damaging one of the UK’s most effective foreign policy tools in recent years. ‘Global Britain’ necessitates considerable additional resources and while the IR emphasises the centrality of diplomacy, it is not clear what resources are actually available.

Relevance

Longer-term, loss of relevance is the most significant risk for post-Brexit UK FSDP. For all the ambition for ‘Global Britain’, a departure from the EU still requires the UK to answer the question of what it can do better outside and independent (or alone). The IR provides some answers, claiming ongoing systemic relevance for the UK and its potential to leverage strong domestic capacities, e.g. in science and technology, to achieve influence in new fields, including artificial intelligence (AI) and cyber. The UK also intends to be an activist power, ‘sitting at the heart of a network of like-minded countries and flexible groupings’, its cooperation ‘highly prized around the world’ (29). This is certainly an important corrective to recent years where it has ‘appeared less ambitious and more absent in its global role’ (30).

Leaving the EU, however, means the UK has lost an important platform through which to exercise influence and underscore its relevance. The IR’s ambition is clear, but how its objectives will be implemented — and therefore how the UK ensures it continues to matter internationally — is less so. Investment in military capacities is important, but a similar financial uplift is also required if its prized diplomatic network is to make ‘Global Britain’ reality. And for all its undoubted capabilities in science and technology, as well as its commercial innovation, it remains unclear how the UK can be a rule-maker, although facilitating and brokering international agreements is certainly achievable.

Data: European Commission, 2021; European External Action Service, 2020

The 2021 G7 and COP26 presidencies provide ideal platforms for the UK to showcase its continuing relevance. However, difficult relations with the EU and the potential for upheaval in Scotland and Northern Ireland are reminders of the fundamental tensions Brexit has exposed and exacerbated. The UK’s international relevance will be determined ultimately by how much attention, resource and leadership it is able to give to global challenges.

EU post-Brexit options

While Europe is no stranger to Britain’s tradition of continental disengagements, Brexit arguably represents the most significant shift in relations in many decades. For many, Brexit remains a brutal dismissal of the entire European post-war project, challenging the very structures of European foreign policy. For others, reassured ‘that the UK’s permanent military commitment to the collective defence of their territories will not change’, there is an opportunity to rework what can be logically and sustainably accomplished abroad in the name of the EU (31).

For the present, the IR has dashed hopes for a post-Brexit realignment with the UK in FSDP. Like it or not, the EU must now accept three certitudes in its dealings with the UK. First, a future of non-institutionalised dealings on FSDP; second, a preference for bilateral and trilateral contact and conventions established by the UK and key member states; third, examples of the UK’s determination to prove itself anything but auxiliary to the EU’s foreign policy goals. These are analysed using the framework of the four ‘Rs’.

Reputation

Visions of Europe as a community of values and the EU as a normative foreign policy actor have long been contested. Brexit represents a further two-fold reputational challenge: ensuring the EU’s original integrationist rationale is still fit for purpose, and preventing its FSDP from becoming a tactical vehicle merely to rebuff Euroscepticism within and beyond the EU. While Brexit represents a major challenge, the systematic deconstruction of democratic and rights-based institutions in Poland and Hungary signifies a far more pernicious ‘drift among member states’ eroding Europe’s foundation of values (32). Flashpoints over Eurozone vulnerabilities, the migration crisis, neighbourhood upheavals, and anti-democratic populist waves demonstrate the EU’s ongoing struggle to anchor its own value set. This has provoked a semi-permanent contestation over the EU’s internal philosophy and its credibility as a foreign policy actor, undermining its ability to operate viably within the structures of the Western-led liberal global order.

How can the EU respond? FSDP (among other policies) relies heavily on differential integration to enable collaboration with third parties. The idea of opting for a looser arrangement of states, or even revisiting the EU’s own goals, has been floated before. Juncker’s 2017 White Paper suggested five different scenarios, each with varying consequences (33). The EU’s own values may limit what is possible, but failing to reground them guarantees domestic impasses and foreign policy blockages. Further refusal by the EU to address its ‘value drift’ will see the ‘integration-disintegration’ fault lines highlighted by Brexit widen in the short term and the ‘permissive consensus’ that enables EU action shift in the long term to a ‘constraining dissensus’ (34).

The EU’s vaccine rollout constitutes the first serious example of post-Brexit EU-UK animosity. Britain shifted from having Europe’s highest COVID death rate to being its vaccine powerhouse. By contrast, the EU struggled with asymmetric national responses over lockdowns and institutional tensions over rescue funding. Limited pre-Brexit UK-EU coordination on vaccine roll-outs collapsed completely in January with the Commission’s ill-fated attempt to impose export controls on vaccines crossing EU borders (specifically the Northern Ireland/UK border). By March 2021, in the face of worsening infection rates and ongoing distribution struggles, the EU had nonetheless exported 21 million doses to the UK and another 77 million to 33 countries abroad, leading European Council President Charles Michel to propose an international treaty to ensure ‘universal and equitable access to vaccines’ (35). Such frameworks herald areas where EU and UK leadership could help future-proof whole regions from global health threats. Shifting the rhetoric from combative to collaborative is key if the EU is to limit the reputational damage from this inglorious episode of intra-regional rivalry.

Responsibility

In reclaiming its reputation, the EU has a number of key responsibilities. Internally, there are opportunities to reform its above-mentioned value set (primarily supporting its commitment to democracy, rule of law and human rights). Reworking its post-Covid budget to ensure growth, rather than stagnation is equally important.

Brexit matters here. The UK’s departure impacted the overall EU budget, requiring strategic redistribution and new funding packages (e.g the Brexit Adjustment Reserve, European Globalisation Adjustment Fund, EU Solidarity Fund, etc.). Although it ‘had a good start to the pandemic’, including the historic agreement to create a €750 billion debt-financed recovery fund, the EU’s recovery is likely to be slower (36). The EU has a responsibility to keep a sharp eye on the need for future stimulus, rising corporate debt, Eurozone investment levels (already declining pre-pandemic) and above all, inflation. The risk is that because Europe’s economy ‘entered the pandemic in a low-inflation, low-growth equilibrium’, it could emerge from Covid in precisely the same state. The challenge is to avoid ‘another lost decade of economic stagnation and political instability’ (37).

The EU’s responsibilities in regional and international cooperation can also be strengthened through regulatory diplomacy, an area where it enjoys strong international credentials. By focusing on the procedural, rules-based structures inherent in complex, multi-level regimes, the EU has an opportunity to expand its own global role. This could include oversight of big data, cybersecurity, data protection rights, intellectual property and major digital platforms involving AI and machine learning. Promoting responsible cybersecurity aligns well with the UK’s own ambitions to be a ‘responsible cyber power’ (38). Similarly, EU support for the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change to enable climate change commitments alongside support for the US President Biden’s focus on global governance are also influential avenues. Even a regulatory approach to values — a much-needed area — is likely to engender lasting cooperation with the UK, including commitments to the European Convention on Human Rights (written into the TCA).

While revisiting the TCA may not fill either side with enthusiasm, urgent discussions are needed in the area of internal security, as emphasised in the recent House of Lords report on Law Enforcement and Judicial Cooperation in Criminal Matters. Despite the general provisions on sharing passenger data, continued UK access to some EU databases, and extradition arrangements, the report highlights the zero-sum outcome entailed in the UK’s third-party status for Eurojust and Europol, the loss of access to the Schengen Information System (SIS II), and specifically the loss of ‘the influence and leadership the UK previously enjoyed in shaping the instruments of EU law enforcement and judicial cooperation’ (39). There is a clear responsibility on both sides to ensure this aspect of the new relationship functions effectively.

Resources

FSDP remains the least communitised area of EU policy. While this makes agreement between member states challenging on occasion, it has the benefit of enabling flexible third-country participation in key areas. In reworking its post-Brexit FSDP, as well as reshaping relations with the UK, the EU requires a ‘philosophy of parallelism’ in which current structures are maintained on the basis of the CFSP/ CSDP, spurring greater opportunities for cooperation with third countries. The EU has a mix of partners. Current relationships range ‘from almost entirely informal to treaty-based’, including potential and full candidate states; the Eastern Partnership and European Economic Area (EEA)/European Free Trade Association (EFTA); and individual partners like Japan, the US and Canada (40). Post-Brexit, this represents a workable spectrum from non-institutionalised foreign policy dialogues (e.g. Norway, EEA) and legally-binding Strategic Partnership Agreements (e.g. Canada) to multi-issue engagement, resting on non-binding declarations boosted by various micro-forums (e.g. the US, supplemented by the E3). Combining wide-ranging third-party flexibility on one hand with uniquely European opportunities on the other, the EU could offer a range of potential FSDP structures/relationships to the UK.

Data: FCDO, 2020

In terms of Security and Defence, the UK will continue its role in NATO via its strategic nuclear deterrent, commitments to support future NATO exercises and regional forward deployment. Further, While the UK often opposed EU defence integration initiatives as a member state, it could potentially pivot to limited support for EU defence ambitions, provided this enhances the UK’s overarching commitment to European regional security. The UK may rework commitments to continued participation in value-based European technology and capability programmes (e.g. the Eurofighter combat aircraft), naval counter-piracy operations, and even the technological and defence benefits of participating in discrete capability programmes including Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO).

The EU would likely find such offers attractive. Brexit has created a major hole in the EU’s defence architecture, absent the UK’s military power, global reach, diplomatic expertise, UN Security Council permanent seat, etc. The UK represented approximately 25 % of the EU’s overall defence spend and 20 % of its national capabilities. Equally, the opportunities to finally move ahead without UK obstruction are clear. Brexit ‘has created considerable momentum in EU security and defence policy’ with four major initiatives: the EU Military Headquarters, PESCO, the European Defence Fund and the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) (41). The question is how to match a hardware-oriented, operations-based arrangement favoured by the UK with a suitably non-institutionalised European format. French President Macron has also proposed a range of options, including a European Council for Internal Security with a mandate to enhance NATO links that could appeal to the UK.

In the short term, forums like the E3, G7, G20, or even the UN Security Council will be crucial venues for post-Brexit EU-UK cooperation. The E3 has since the early 2000s operated as ‘a semiregular feature of European diplomacy across an array of foreign policy and security issues’, key in finalising the 2015 JCPOA alongside China, Russia and the US (42). While its activity has increased post-Brexit, to be truly effective the E3 structure needs to identify strategic areas appropriate for regular cooperation in which its specific trilateral format is beneficial. The use of agile and flexible micro-coalitions is likely to remain a central feature of European foreign policy. However, whether the E3 or G7 evolves into a new wellspring of European diplomacy remains to be seen.

Renewed attention to UK bilaterals with key EU member states is likely, including the UK-France Lancaster House Treaties (focused on bilateral military cooperation) and a reworked Sandhurst Treaty (tackling illegal migration). In addition, a more formalised EU-US-UK ‘Transatlantic 3’ structure focusing on areas of global strategic importance (climate change, democracy, anti-corruption, global health) could yield serious positives. US President Biden is likely to proffer global support for EU leadership in bilateral or trilateral formats in exchange for a permanent reduction in UK-EU tension, helping to bring London and Brussels closer.

Relevance

The EU’s biggest post-Brexit challenge is remaining relevant both to its own citizens and the wider world, something the planned Conference on the Future of Europe is intended in part to address. In the eyes of some, ‘the EU has ceased to be sufficiently attractive’, with Brexit ‘undermining its ability to promote its model as well as its norms and values towards third states’ (43). For others, Brexit neither undermines the EU’s soft power nor its presence in international affairs. Encouragingly, as Balfour notes, ‘the rationale for finding pragmatic solutions to cooperate on a host of foreign and security policy themes has generally been strong’ (44). While the climate crisis and COVAX-generated vaccine diplomacy offer obvious opportunities for cooperation at the global level and in international forums, identifying parallelisms in areas still redolent in UK eyes of EU dirigisme may take time (even in defence where the UK enjoys comparative advantages). Further afield, the EU should identify opportunities to encourage UK support in crisis management (e.g. CSDP participation); coordination on sanctions (e.g. Myanmar/Burma, China); building on previous UK contributions to the EU’s sanction regime (e.g. Russia); and operations in areas where the UK remains a policy-shaper (e.g. Western Balkans, Middle East, Eastern Mediterranean, etc.).

The EU’s continuing relevance to the UK itself will be institutionalised through the two new treaty-based governance structures: the TCA Partnership Council and the UK-EU Joint Committee servicing the Withdrawal Agreement. Formal relations will also rely on the UK Mission to Brussels and the EU Delegation to the UK. As long as the UK remains inclined ‘at every turn to downplay the significance’ of its relationship with the EU, these intra-governance structures and institutional frameworks will remain largely untested (45). Priority should therefore be given to identifying those areas within the TCA likely to generate lasting and symbiotic EU-UK cooperation at the international level.

Conclusion

While the UK’s contractual relationship with the EU as a member state is over, less formal, medium-term options are explored below. The EU needs to resist the temptation for off-the-shelf, Framework Participation Agreements and look instead at what can reasonably be offered, on the basis of need, viability and external impact. As always, solid dialogue on the basics engenders commitment on the complex. In a sense, post-Brexit foreign policy is a product of the pandemic: the UK is keen to be seen — at home and abroad — as ‘socially distancing’ itself from the institutions of the EU.

The EU needs to brace itself in the short term for a barrage of examples in this respect, appreciating that for the next five years at least, the sum total of UK foreign affair outputs will be steeped in performance, as much as substance. What is hoped is that despite the evident ‘symbolism of taking sovereign decisions independently of the EU’ (46), the UK will continue to identify non-EU formats like CSDP, EI2, the E3 and even the proposed European Security Council as avenues with which to keep Britain broadly engaged in Europe’s overall foreign policy goals. In the meantime, the EU must not sit still. The upcoming Conference on the Future of Europe, as well as intense work across institutions with a foreign affairs remit, together need to identify a range of outward-facing opportunities, beginning with an updated Covid-proof Global Strategy.

References

* The title of this Brief makes reference to an apocryphal British newspaper headline 'Fog in Channel, Continent Cut Off'.

(1) HM Government, ‘Political Declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship between the European Union and the United Kingdom’,19 October 2019 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/840656/Political_Declaration_setting_out_the_framework_for_the_future_relationship_between_the_European_Union_and_the_United_Kingdom.pdf).

(2) HM Government, ‘Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, 16 March 2021 (https:// www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age- the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy).

(3) Wintour P., ‘UK risks losing global influence if it quits single market, says former civil servant’, The Guardian, 8 November 2016 (https://www.theguardian. com/politics/2016/nov/08/uk-risks-losing-global-influence-quits-single- market-senior-civil-servant).

(4) European External Action Service, ‘After Brexit, how can the EU and UK best cooperate on foreign policy?’, HR/VP Blog, 29 January 2021 (https://eeas.europa. eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/92345/after-brexit-how-can-eu- and-uk-best-cooperate-foreign-policy_en).

(5) Hansard, ‘Integrated Review: Statement by Boris Johnson to the House of Commons’, 17 March 2021 (https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2021-03-17/ debates/32EE8995-85E7-4515-AB82-5067BFB02CFA/IntegratedReview).

(6) Foster P., ‘New financial forum fails to heal EU-UK divisions’, Financial Times, 16 April 2021 (https://www.ft.com/content/310ec085-6b65-4d10-a0a0- 1a97f83c8882).

(7) Prime Minister’s Office, ‘Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s speech in Greenwich’, HM Government, London, 3 February 2020 (https://www.gov.uk/ government/speeches/pm-speech-in-greenwich-3-february-2020).

(8) HM Government, ‘Prime Minister announces merger of Department for International Development and Foreign Office’, 17 June 2020 (https://www.gov. uk/government/news/prime-minister-announces-merger-of-department- for-international-development-and-foreign-office?utm_source=80ae1729-d25d-490a-bd36-fe88591fb17a&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=govuk- notifications&utm_content=immediate).

(9) HM Government, ‘Defence secures largest investment since the Cold War’, 19 November 2020 (https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-secures- largest-investment-since-the-cold-war).

(10) HM Government, ‘Changes to the UK’s aid budget in the Spending Review’, 25 November 2020 (https://www.gov.uk/government/news/changes-to-the- uks-aid-budget-in-the-spending-review?utm_source=5c537462-e108- 4957-b327-cacd4595df12&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=govuk- notifications&utm_content=immediate).

(11) Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy , p. 11, op.cit.

(12) ‘Northern Ireland Secretary admits new bill will “break international law”’, BBC News, 8 September 2020 (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk- politics-54073836).

(13) House of Commons Library, ‘UK Internal Market Bill: Lords amendments explained’, Briefing Paper, No 9051, 4 December 2020 (https://commonslibrary. parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9051/).

(14) ‘US trade deal: Internal Market Bill will scupper pact, Johnson is warned’, Belfast Telegraph, 10 November 2020 (https://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/news/ brexit/us-trade-deal-internal-market-bill-will-scupper-pact-johnson-is- warned-39727530.html).

(15) European Commission, ‘Withdrawal Agreement: Commission sends letter of formal notice to the United Kingdom for breach of its obligations under the Protocol on Ireland and Northern Ireland’, 15 March 2021 (https://ec.europa.eu/ commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_1132).

(16) Harvey F., ‘Boris Johnson told to get grip of UK climate strategy before Cop26’, The Guardian, 12 April 2021 (https://www.theguardian.com/ environment/2021/apr/12/boris-johnson-told-to-get-grip-of-uk-climate- strategy-before-cop26).

(17) Nardelli A. and Reynolds I., ‘Japan pushes back against U.K. plan to boost G-7 Asia reach’, Bloomberg, 27 January 2021 (https://www.bloomberg.com/news/ articles/2021-01-27/japan-pushes-back-against-u-k-plan-to-boost-g-7- reach-in-asia).

(18) HM Government, ‘Hong Kong and China: Foreign Secretary’s statement in Parliament’, 20 July 2020 (https://www.gov.uk/government/ speeches/hong-kong-and-china-foreign-secretarys-statement-in-parliament?utm_source=bd2eedc8-07a7-47e2-9630-b0fb520266da&utm_ medium=email&utm_campaign=govuk-notifications&utm_ content=immediate).

(19) Cowburn A., ‘Government refuses to say if MPs will be given vote on multi- billion pound aid cut’, The Independent, 2 March 2021 (https://www.independent. co.uk/news/uk/politics/overseas-aid-cut-yemen-james-cleverly-b1810465. html).

(20) HM Government, ‘A force for good: Global Britain in a competitive age’, 17 March 2021 (https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/a-force-for-good-in-a-competitive-age-foreign-secretary-speech-at-the-aspen-security- conference).

(21) Wintour P., ‘UK diplomats told to cut up to 70% from overseas aid budget’, The Guardian, 26 January 2021 (https://www.theguardian.com/global- development/2021/jan/26/uk-cut-overseas-aid-budget-costs?CMP=Share_ AndroidApp_Other).

(22) Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, p.19, op.cit.

(23) HM Government, ‘Defence secures largest investment since the Cold War’, 19 November 2020 (https://www.gov.uk/government/news/defence-secures- largest-investment-since-the-cold-war).

(24) Statista, ‘Number of personnel in the armed forces of the United Kingdom (UK) from 1900 to 2020’, 27 January 2021 (https://www.statista.com/ statistics/579773/number-of-personnel-in-uk-armed-forces/).

(25) HM Government, ‘Defence Secretary oral statement on the Defence Command Paper’, 22 March 2021 (https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/ defence-secretary-oral-statement-on-the-defence-command-paper).

(26) Busby M., ‘Labour criticises cuts after leaked MoD report says army low on troops’, The Guardian, 6 February 2021 (https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/feb/06/labour-criticises-cuts-after-leaked-mod-report-says- army-low-on-troops).

(27) Savage M., ‘Cuts to diplomatic service will reduce Britain’s influence, MPs warn’, The Guardian, 16 June 2019 (https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2019/ jun/15/cuts-to-diplomatic-service-will-reduce-britains-influence-mps-warn).

(28) Binyon M., ‘Diplomatic Deficit’, Diplomat Magazine, 1 December 2015 (https://diplomatmagazine.com/diplomatic-deficit/).

(29) Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, pp. 6-7, op.cit.

(30) House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, ‘A brave new Britain? The future of the UK’s international policy’, Fourth Report of Session 2019- 21 (HC380), 22 October 2020, p. 7 (https://committees.parliament.uk/ publications/3133/documents/40215/default/).

(31) Shea J., ‘The UK and European defence: Will NATO be enough?’, in Hug A. (ed), Finding Britain’s role in a changing world: Partnerships for the future of UK Foreign Policy, The Foreign Policy Centre, London, 2020, p. 22 (https://fpc.org.uk/ publications/partnerships-for-the-future-of-uk-foreign-policy/).

(32) Balfour R., ‘Raising Europe’s Global Role Starts at Home‘, Carnegie Europe, 16 July 2020 (https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/82311).

(33) Hadfield A., ‘EU Foreign Affairs and the Future: Multi-level Opportunities vs. Multi-layered Risks’ in Damro C., Heins E. and Scott D. (eds), European Futures: Challenges And Crossroads for the European Union of 2050, Routledge, 2021.

(34) Down I. and Wilson C., ‘From ‘Permissive Consensus’ to ‘Constraining Dissensus’: A Polarizing Union?’ Acta Politica, Vol. 43, 2008, pp. 26–49.

(35) Peseckyte G., ‘New international treaty will help prepare for future pandemics, EU’s Michel says’, Euractiv, 31 March 2021 (https://www.euractiv. com/section/coronavirus/news/new-international-treaty-will-help-prepare- for-future-pandemics-eus-michel-say/).

(36) Odendahl C. and Springford J.‚ ‘Why Europe should spend big like Biden’, Centre for European Reform, 29 March 2021 (https://www.cer.eu/publications/ archive/bulletin-article/2021/why-europe-should-spend-big-biden).

(37) Ibid.

(38) Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy’, p. 9, op. cit.

(39) House of Lords, ‘Beyond Brexit: policing, law enforcement and security’, 2021, p. 3 (https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld5801/ldselect/ ldeucom/250/250.pdf).

(40) I. Bond, ‘Post-Brexit foreign, security and defence co-operation: we don’t want to talk about it’, Centre for European Reform, 26 November 2020, p.4.

(41) Martill B. and Sus M., ‘Post-Brexit EU/UK security cooperation: NATO, CSDP+, or ‘French connection’?’, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, Vol. 20, No 4, 2018, p. 851.

(42) Brattberg E., ‘The E3, the EU, and the Post-Brexit Diplomatic Landscape’, Carnegie Europe, 18 June 2020 (https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/06/18/e3- eu-and-post-brexit-diplomatic-landscape-pub-82095).

(43) Weilandt R., ‘Why Brexit’s impact on EU foreign policy might remain limited’, Crossroads Europe, 17 August 2017 (https://crossroads.ideasoneurope. eu/2017/08/17/article-14/).

(44) Balfour, R., ‘European Foreign Policy After Brexit‘, Carnegie Europe, 10 September 2020 (https://carnegieeurope.eu/ strategiceurope/82674#:~:text=It%20was%20never%20going%20 to,international%20sanctions%20and%20dealing%20with).

(45) Jack, M. and Rutter, J., ‘Managing the UK’s Relationship with the European Union’, Institute for Government, 2021, p. 5 (https://www.instituteforgovernment. org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/managing-uk-relationship-eu.pdf).

(46) ‘Post-Brexit foreign, security and defence co-operation: we don’t want to talk about it’, op.cit.