Russia deploys a variety of hybrid tactics to reshape the current global political landscape. It does so in a post-unipolar and post-hegemonic world. However, this is also a world where the Russian state has to contend with both the strengths of other powers and its own internal structural deficiencies.

How can we better understand the hybrid nature of this state, which seeks to compensate for its relative weaknesses while adjusting to the shifting dynamics of great power rivalry? A helpful metaphor for understanding how the regime challenges the existing global order while also adapting to it is that of the bricoleur (‘tinkerer’). Both Russia’s culture of military innovation and the Wagner enterprise offer useful illustrations of how this concept, borrowed from French social theory (1), can enhance our understanding of what kind of adversary Russia is.

Moscow's machinations

Rather than a traditional, bureaucratic entity weighed down by inertia, the Russian regime operates as an opportunistic, improvisational purveyor of ad hoc ‘assemblages’ pieced together from a diverse but limited repertoire of elements. Driven by expediency, it exploits fragilities in the global system. However, it also remains significantly vulnerable to unforeseen events and developments.

Viewing the regime as a bricoleur, a clever improviser devising makeshift but sometimes highly effective stratagems, highlights some key characteristics that other commonly employed metaphors such as ‘mafia’, ‘court’, or ‘machine’ often overlook or even obscure.

Severe limitations have historically impeded the realisation of ambitious Russian military visions.

The mafia (2) metaphor underscores the ruling elite’s clan-based structure, the thuggish behaviour of the siloviki (the security elite), the regime’s links to organised crime (3) and its tendency to disregard conventional norms. However, while intimidation and public displays of brutality, as well as the blurring of lines between government and business, are characteristic of the Russian state, these traits are not exclusive to mafia-like governance. The court (4) metaphor vividly evokes intrigue and the pursuit of favour with a supreme ruler in a hierarchical setting far removed from everyday society. But it also implies a structured and orderly environment. The reality of the Russian state is much messier, more improvised and chaotic than this image might suggest. The machine (5) metaphor highlights reliance on routine and a lack of substantial reform at the heart of the Russian state apparatus. Yet the notion also creates a misleading sense of efficiency and coherence.

Military technology: Tinkering to catch up

Russian strategic culture leans towards a more holistic, deductive and relational approach to thinking (6). While it exhibits contradictions, these are seen as less problematic when viewed through a dialectical lens. The Russian strategic mindset often combines diverse assets and resources to compensate for its inferiority vis-à-vis adversaries, while asymmetrically exploiting their weaknesses. In this perspective, technology is not seen as a substitute for manpower on the battlefield but rather as a tool that enhances human capabilities. The calculus of military inferiority, a constant in Russia’s military thinking for centuries, is key here, reflected inter alia in the general strategy of ‘active defence’ against NATO, focused on asymmetrical tactics to disrupt and degrade enemy forces (7). Foresight and deep understanding of change as nonlinear and discontinuous is a trademark of Russian strategic thinking – even when the requisite technology for such change was only available to Russia’s adversaries (8). So is the capacity to revisit and adapt old military concepts, such as ‘deep operation’ (Глубокая операция), aiming to sow chaos behind enemy lines, to new conditions.

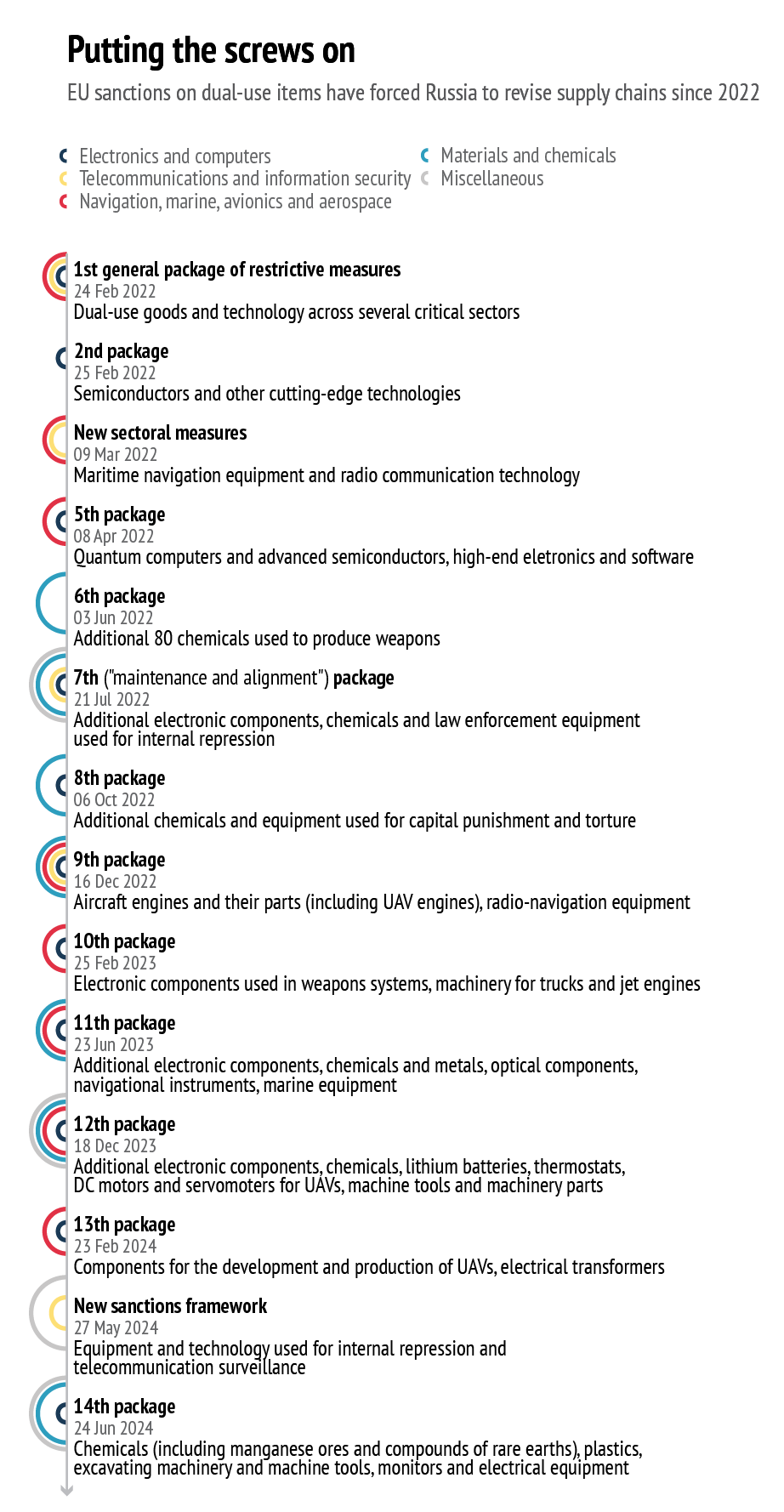

Data: EUISS research based on Decisions by the Council of the European Union

However, severe limitations have historically impeded the realisation of ambitious Russian military visions. Strategic foresight does not easily translate into operational effectiveness. Throughout the current war in Ukraine, Moscow has been better at managing immediate problems than anticipating forthcoming challenges, although it has demonstrated some ability to adapt through organisational changes, scaling up production and modernising designs across the military and the defence industry. These design adaptations include improving sophisticated missile systems like the Kh-101 and strike patterns, as well as adding cage armour to its armed vehicles to protect against First Person View (FPV) drones (9). More generally, however, the regime often lacks the material and organisational resources to transform its strategic visions into reality. As a result, it resembles a builder with ambitious and well-conceived plans but insufficient means to execute them.

Wagner: Living dangerously

The Wagner Group was another typical bricoleur creation, designed to circumvent other actors’ strengths in the global geopolitical ‘game of shadows’. Conceived by the GRU, Russia’s military intelligence, it evolved into an entrepreneurial network with distinct network features like horizontality, spontaneous reorganisation, and adaptability. Wagner was a private military company (PMC) but also a proxy for the related moneymaking empire (otherwise known as ‘Concord’) financed through concessions from host governments, as well as a number of outlets dedicated to manipulating the information environment. This composite entity provided cost advantages and avenues for Russia to pursue its state interests abroad – from scoring military victories (Bakhmut) and recruiting for the war on Ukraine to conducting covert and deniable influence operations elsewhere.

Despite being repurposed several times since its initial appearance in Ukraine after 2014, the Wagner enterprise ultimately lacked a crucial feature of networks: resilience to shocks. Yevgeny Prigozhin’s mutiny and subsequent assassination on 23 August 2023 spelled its demise as it succumbed to predatory pressures inside the state that were not merely a consequence but rather the catalyst of that summer’s events. Wagner was never a truly ‘private company’.

It was always an integral part of Russia’s hybrid foreign policy toolbox. However, it grew too big, rich and independent – creating a rift with the top military echelons. As a result, it was dismantled, with its elements mostly either integrated into existing structures such as Rosgvardia in Ukraine or rebranded and placed under tighter GRU control such as the Africa Corps.

The Wagner Group’s impact has tended to be overestimated in the Western commentariat. Rather than a masterly creation and an invisible hand orchestrating political movements in Africa and elsewhere, it was more of a bricoleur invention designed to compensate for Russia’s relative weaknesses in the arena of great power competition. While moderately successful in suppressing rebel groups, it failed to eliminate them or create lasting security – and so was never likely to serve as a viable means for Moscow to solidify its position or establish enduring influence.

At home, Wagner’s collapse was a testimony to the tensions and frictions within the regime. Its demise satisfied internal bloodlust and pursuit of parochial interests – while at the same time reducing the state’s capacity to act abroad. Wagner was a unique creation designed to respond to the reality of growing global contestation. But it was a temporary fix, cobbled together bricolage-style. None of its successors, whether acting individually or collectively, can replicate Wagner’s achievements.

Defeating the bricoleur

How can the bricoleur perspective provide insights into developing more effective policies to counter the challenge that the regime poses to the West?

First, the perspective offers a platform for a clear-eyed assessment of the regime’s strengths and weaknesses. Viewing the Kremlin regime as a bricoleur allows us to recognise its potential for creativity and adaptation. But it also highlights the regime’s inherent weaknesses. Russia’s long history of military inferiority has honed the ability of successive rulers in Moscow to innovate and strategise to limit adversaries’ advantages. However, the regime has failed to turn sound strategic plans and good foresight into successful operational practice, engaging in technological bricolage to fix immediate problems rather than to gain the upper hand in the long run. Wagner, an innovative and highly adaptive means of projecting Russian influence abroad, was created primarily to indirectly compete with other powers in Africa and the Middle East. But ultimately it fell victim to the intrinsically hybrid nature of the bricoleur regime that created it.

The war has reverberated across the post-Soviet space, prompting some former imperial peripheries to gravitate towards the EU.

The image of the Kremlin as a skilful orchestrator of chaos, a flawless strategist, and a chess master – cold and calculating, always several moves ahead of the ‘leaderless’ West – needs to be dispelled. Moscow does opportunistically exploit, and sometimes exacerbate, political fragmentation in the West, while also stoking anti-Western sentiment in the emerging world. It uses its own normative power to actively undermine Western influence and to fuel internal dissent in Western societies, and establish a shared platform for engaging with authoritarian leaders, based on the instrumentalisation of ‘traditional values’. But the regime’s bricoleur nature underscores the limitations of its broader ambitions.

A clearer understanding of the Kremlin’s influence is vital in order to avoid both underreacting and overreacting to the challenges it poses and to focus strategically on how best to weaken it. While the Russian regime has contributed to a more contested global order, it also responds to the unpredictable dynamics that come with it – often failing or paying a heavy price just to secure rather than expand its position. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine can be seen from this perspective as an immensely costly failure of coercive strategy aimed at maintaining a particular droit de regard for Moscow in the former USSR region – with the ultimate outcome still uncertain. What is certain is that the war has reverberated across the post-Soviet space, prompting some former imperial peripheries (Ukraine, Moldova and Armenia) to gravitate towards the EU, as well as NATO’s swift expansion in the north.

Western efforts should focus on Russia’s struggles to navigate the more contested world it has helped create. By systematically exposing the frictions and contradictions in Russia’s engagement in the Global South, Western countries can increase the costs for Moscow of legitimising its actions. For example, it is crucial to fully exploit the fact that Wagner and its successors’ activities have come at a terrible human cost to local populations (10) and regularly involved the plundering of African wealth and resources, which were then exported from the continent (11). Similarly, the ‘Normative Power Russia’ narrative, portraying Russia as a conservative paradise while at the same time deploying an anti-imperialist discourse targeting the ‘world majority’ (мировое большинство) that Russia seeks to alienate from the West, should be exposed as hypocrisy. Russia’s history of brutal imperial expansion and colonisation, including its current attempt to recolonise Ukraine, and the decadent materialism of the Russian ruling elite speak for themselves. However, the message they convey deserves greater amplification.

Second, to weaken Russia’s ability to wage its imperial war on Ukraine, the traffic in sensitive hardware – frequently used as makeshift substitutes for sanctioned components – should be better regulated through tighter export controls. Take the example of the previously mentioned Kh-101 cruise missile used to hit a children’s hospital in Kyiv in July, reportedly containing dozens of foreign-produced parts – many from Western companies including Texas Instruments and Intel. What will the bricoleur do when he finds his local hardware store empty?

Finally, the EU should undertake its own reforms to limit its vulnerabilities and effectively counter Russia’s hybrid tactics. It should have faith in its ability to contain and, in the long term, defeat the Kremlin, whose ideological foundation is another improvised construct – flexible and adaptable, but also inherently unstable. In the meantime, it should spare no efforts to build credible deterrence for the future and strengthen the resilience of its open democratic societies based on liberty, solidarity and the rule of law – the best defences against tyranny it has ever produced.

References

* The author would like to thank Pelle Smits and Carole-Louise Ashby for their invaluable research assistance.

1. See in particular Lévi-Strauss, C., La pensée sauvage, Plon, Paris, 1962; Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F., L’Anti-Oedipe, Editions de Minuit, Paris, 1972; de Certeau, M., L’invention du quotidien, Gallimard, Paris, 1990.

2. See e.g. Gessen, M., ‘Putin: The rule of the family’, New York Review of Books, 4 March 2016; ‘Prigozhin’s death shows that Russia is a mafia state’, The Economist, 24 August 2023; Lucas, E., ‘Late Putinism: Mafia State’, CEPA, 27 August 2023 (https://cepa.org/article/late-putinism- mafia-state/).

3. Galeotti, M., We Need to Talk about Putin: How the West gets him wrong, Penguin, London, 2019; Galeotti, M., The Vory: Russia’s Super Mafia, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2018.

4. See e.g. Zygar, M., All the Kremlin’s Men: Inside the court of Vladimir Putin, PublicAffairs, New York, 2016.

5. See e.g. McKew, M., ‘Putin’s real long game’, Politico, 1 January 2017 (https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/01/putins-real-long- game-214589/).

6. Adamsky, D., The Culture of Military Innovation, Stanford University Press, Stanford, 2010.

7. Kofman, M. et al., Russian Military Strategy: Core tenets and operational concepts, Center for Naval Analyses, Washington, 2021 (https://www. cna.org/reports/2021/08/Russian-Military-Strategy-Core-Tenets-and- Operational-Concepts.pdf).

8. The Culture of Military Innovation, op.cit.

9. Ryan, M., ‘Russia’s adaptation advantage’, Foreign Affairs, 5 February 2024.

10. Human Rights Watch, ‘Central African Republic: Abuses by Russia-linked forces’, 3 May 2022 (https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/05/03/central- african-republic-abuses-russia-linked-forces); UNHCR, ‘Rapport sur les évenements de Moura du 27 au 31 mars 2022’, 2023 (https://www.ohchr. org/sites/default/files/documents/countries/mali/20230512-Moura- Report.pdf); US State Department, ‘The Wagner Group’s atrocities in Africa: Lies and truth’, 8 February 2024 (https://www.state.gov/the- wagner-groups-atrocities-in-africa-lies-and-truth/); ACLED, ‘The Wagner Group’s new life after the death of Yevgeny Prigozhin’, 21 August 2024 (https://acleddata.com/2024/08/21/qa-the-wagner-groups-new- life-after-the-death-of-yevgeny-prigozhin/).

11. Patta, D. and Carter, S., ‘How Russia’s Wagner Group funds its role in Putin’s Ukraine War by plundering Africa’s resources’, CBS News, 16 May 2023 (https://www.cbsnews.com/news/russia-wagner-group-ukraine- war-putin-prigozhin-africa-plundering-resources/); US Department of the Treasury, ‘Treasury sanctions illicit gold companies funding Wagner forces and Wagner Group facilitator’, Press release, 27 June 2023 (https:// home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1581).