There is no shortage of difficult cases for conflict prevention around the world, but Mozambique is a particularly interesting one and could mark a defining moment for the international community’s approach to this challenge. Since its independence from Portugal in 1975, Mozambique has alternated two long periods of war and peace: first, a 15 year-long civil war between the ruling party, the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO) and the rebel forces of the Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO), which caused over one million deaths and displaced five million people; then, since the signature of the Rome General Peace Accords in 1992, almost 20 years of peaceful transition to democracy and steady GDP growth, averaging 7% between 2003 and 2013.1 Just when Mozambique was beginning to be regarded as a successful example of post-conflict peacebuilding,2 the resurgence of low-intensity armed conflict between RENAMO and FRELIMO in the period 2013–2016 provided an unexpected reality check, revealing the dangers of a flawed democratisation process.

Yet, the sources of instability in today’s Mozambique are no longer limited to the politico-military confrontation between RENAMO and FRELIMO. A dangerous mix of old and new dynamics have been dragging Mozambique into a spiral of fragility and violence; meanwhile, a debt crisis halted the foreign investment bonanza in 2016, as the discovery of undisclosed government loans worth $2 billion3 led to the withdrawal of contributions by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Group of 14 budget support donors,4 a drop of 75% in foreign investments, a currency crisis, and a sharp decline in economic growth which fell from 7.4% in 2014 to 3.4% in 2017.5

Finally, in early March 2019, Cyclone Idai swept through Mozambique’s central provinces, destroying entire towns and villages in its path, killing hundreds of people and affecting thousands in what the UN has described as one of the worst weather-related disasters ever to hit the southern hemisphere. While the full effects of the humanitarian catastrophe are yet to be determined, the World Food Programme believes that 1.7 million people will need help as a result of the disaster,6 inevitably creating risks for stability.

Against this backdrop, what can be done to mitigate conflict risks before it is too late? This Conflict Series Brief seeks to provide answers to these questions by telling two stories about stability in Mozambique. One is about peacebuilding, and what factors contributed to a resurgence of the RENAMO-FRELIMO conflict in 2013; the other one is about conflict prevention, looking at what other forms of violence have been unfolding, and the measures that might be taken to avoid their escalation. As the following sections will show, Mozambique is no longer an early-warning case study: the current situation in the country is a wake-up call to the international community to take action, and a test case for effective conflict prevention, requiring changes in the way local actors cooperate so that risks of violent conflict are identified before they translate into a crisis.7 The conclusion outlines how multilateral actors and bilateral donors, in particular the European Union, might accordingly better target their initiatives in order to maximise their impact and effectiveness.

From civil war to civil peace: historical backdrop

The Mozambican civil war began in 1977 when RENAMO, an armed rebel group supported by Rhodesia (as it was then) and South Africa, launched a guerrilla campaign against the FRELIMO government, opposing its Marxist ideology and policies.8 By the end of the war in 1992, Mozambique was on its knees. Destruction wrought by the war, droughts and famine had decimated its natural resources and physical infrastructure. Large swathes (approximately 40%) of agricultural, communications, and administration infrastructure were destroyed, and the health care system was severely damaged, with dramatic implications for total war-related deaths, estimated at one million.9 Indiscriminate violence during military operations had led to countless human rights violations and large-scale massacres, like that which took place in the southern village of Homoine in 1987, with a death toll of 424.

The cessation of armed conflict, under the 1992 Rome General Peace Accords, relied on a disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration (DDR) process for 90,000 combatants from both RENAMO and the Mozambican Armed Forces, overseen by the United Nations Operation in Mozambique (ONUMOZ). Despite the relative success of the peace agreement and the resulting stability, which lasted until the RENAMO insurgency in 2013, the roots of many persisting political problems in Mozambique can be traced to the end of the civil war and the deployment of the ONUMOZ mission, and in particular to issues relating to disarmament and decentralisation.10

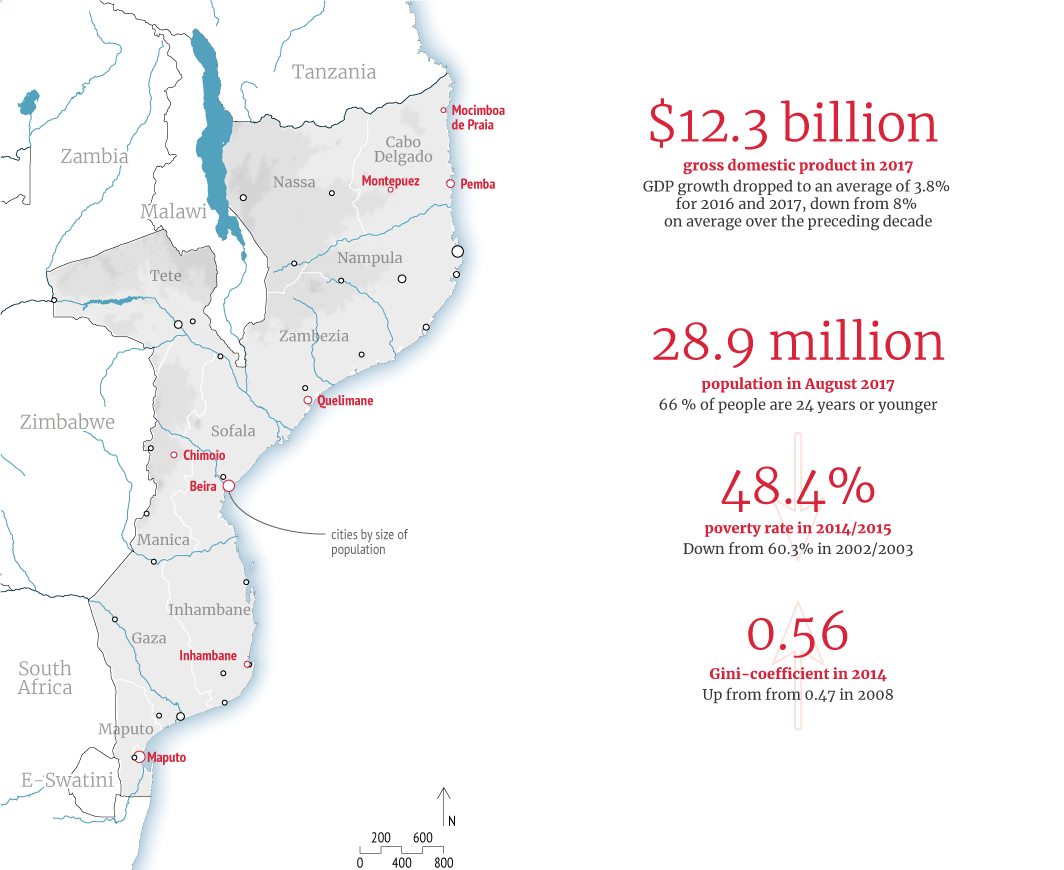

Figure 1: Mozambique: map and key dates

Data: GADM, 2019; Natural Earth, 2019

Disarmament was not prioritised in the DDR programme, for fear of undermining the peace process, given mistrust between the government and the opposition, and their reluctance to surrender arms and integrate troops.11 RENAMO combatants often handed over old weaponry and hid arms caches across the country as an ‘insurance policy’. It has been suggested that over 20,000 arms may still be in the possession of RENAMO, although the exact number is unknown. This allowed RENAMO to always keep the military option open during peacetime, and exploit it for political gain.12

Decentralisation was first introduced in the context of the institutional reforms that followed the 1992 peace accords, in response to the need to create a political space for RENAMO. The government saw decentralisation as a way of improving relations with the rural population. Nevertheless, the 1994 presidential elections demonstrated the potential threat posed by decentralisation to FRELIMO, as results revealed widespread support for RENAMO in many rural areas. The parliament consequently declared the devolution law unconstitutional in November 1995 and passed a constitutional amendment, which created a parallel system of local governance with two levels of administration: the provinces and the districts accountable to the central government, and the municipalities with devolved autonomous powers, competencies and resources. This system contributed to the consolidation of FRELIMO as the country’s dominant political force, by enhancing the control that the party exerts at the local level,13 thereby paving the way for a return of insurgency.

Back to square one: the revival of the RENAMO insurgency

The re-establishment of wartime military bases in the Gorongosa Mountains by RENAMO leader Afonso Dhlakama in late 2012 and RENAMO’s attack on a police station in Muxungue, Manica province, in April 2013, in retaliation for a police raid on RENAMO’s local headquarters in Muxúnguè and Gondola, were the events that triggered the return of insurgency in Mozambique. The causes were multiple: the shortcomings of an incomplete DDR process, generating grievances such as frustration related to the fact that RENAMO ex-combatants were not eligibile for pensions to which former FRELIMO soldiers were entitled; RENAMO’s only partial transition to a political party; FRELIMO’s monopoly of political power and authoritarianism; and the emergence of a younger, post-civil war RENAMO generation believing that the use of force is the only way by which FRELIMO might be induced to cede power.14

The conflict can be divided into two phases: the 2013-2014 insurgency, with a ceasefire signed in August 2014 in advance of the October 2014 general elections, and the renewed conflict that followed the disputed elections, which resulted in Filipe Nyusi being elected as President and FRELIMO maintaining majority control of the Assembly. On 27 December 2016, RENAMO unexpectedly declared a unilateral truce, which was subsequently extended twice, before being extended indefinitely in May 2017. Peace talks resumed. In March 2017, President Nyusi announced the creation of a Contact Group15 to support peace negotiations, co-chaired by the Swiss and American Ambassadors, including China, the European Union, Norway, and the High Commissioners of Botswana and the United Kingdom. Talks between Nyusi and Dhlakama, with the support of the Contact Group, led to a decentralisation agreement incorporating constitutional amendments,16 allowing for the indirect election of mayors, provincial governors and district administrators; and to the signature of a memorandum of understanding on military affairs allowing for the launch of a second DDR process.17

In view of the upcoming October 2019 presidential elections, both parties are now interested in securing a peace agreement. FRELIMO perceives a successful peace process as being to its own electoral advantage, even though it remains reluctant to give up power. RENAMO, despite the failure of the post-civil war DDR, is confronted with a base eager to participate in the political process – with more or less open rent-seeking objectives.18

An important feature of the peace process is the fact that negotiations were conducted at the highest political level, through a dialogue between Nyusi and Dhlakama that excluded members of their respective parties. This made it easier to finalise agreements and avoid exacerbating tensions. However, especially after the sudden death of Dhlakama on 3 May 2018, a key challenge going forward will be how to turn a top-down, exclusive approach into an inclusive, sustainable process that includes the base of both parties.19 RENAMO’s new President, Ossufo Momade, elected on 17 January 2019, will have the responsibility to oversee this complex process. This will be neither an easy nor a painless task. On the one hand, Momade is seen as a voice of moderation and reconciliation, and as the right person to support a political transition for RENAMO. On the other hand, he will have to take into account the implications of the October 2018 municipal elections, during which RENAMO’s electoral successes in 8 municipalities were overshadowed by blatant irregularities in many other municipalities, particularly in Marromeu,20 setting a precedent for potential widespread fraud in the next elections. A fraudulent electoral process is indicative of the peace process not being inclusive, as it shows that mistrust still reigns among the political parties. Weakening public support for FRELIMO aggravates internal cleavages. Too many concessions to RENAMO may entail a loss of rents and privileges, which makes the party apparatus prone to resort to fraudulent practices to maintain its position. RENAMO is tempted by the political transition, but afraid that a corrupt system will prevent it from obtaining a legitimate victory.

Against this backdrop, the political agenda in 2019 will be dominated by the elections, the political transition within RENAMO under the new leadership and the attempts to sign a permanent peace agreement before Mozambicans head to the polls. In a climate of mistrust, a peace agreement on paper, without concrete measures to implement DDR and create trust between the parties, would significantly increase the likelihood of a relapse into violence, especially during/after the elections.21 The situation could deteriorate further as new threats to stability are emerging beyond the confrontation between the two parties.

The rise of violent extremism in Cabo Delgado

Since the October 2017 attacks on three police stations in Mocimboa de Praia, 150 fatalities were reported in both battles and violence against civilians in the province between 1 October 2017 and 30 June 2018. At least half of these occurred between 15 May and 30 June 2018.22

Little is known about the group responsible. Research23 suggests that there are between 350 and 1,000 militants, organised in cell-based structures with each cell comprising 10-20 individuals using basic weaponry and tactics. These cells operate relatively autonomously, have flexible chains of command, and follow their own strategy in areas under their control. Members of the group are recruited directly through family networks, friends, or in mosques, or have been recruited indirectly through video propaganda used by radical movements in Kenya and Tanzania, which has been spread in Mocímboa da Praia and surrounding districts.24

Figure 2: Cabo Delgado province

Data: GADM, 2019; Natural Earth, 2019

Despite uncertainty about the origins, motivations, and support base of the insurgents, three main debates have emerged.

The first debate is between alarmists who fear the emergence of a new Boko Haram, and those who caution against securitising the insurgency in Cabo Delgado. In relation to this debate, the government has alternated between expressing alarm and seeking to minimise the threat. In several instances, it downplayed the Islamist insurgency as the work of a few criminal individuals. However, President Nyusi warned the United Nations General Assembly on 26 September 2018 that the ‘groups of malefactors’ in Cabo Delgado ‘will tend to spread to neighbouring countries’ in the absence of international cooperation.25 Moreover, Mozambique entered into security agreements with Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Uganda, set up a regional military command, moved more troops into the north,26 and passed an anti-terrorism law in April introducing heavier sentences. The government also closed and destroyed mosques,27 and arrested hundreds of people in response to the attacks, including 189 Islamist suspects currently standing trial. These measures have prompted experts to warn against the danger of alienating the Muslim population (approximately 18% of the total population, mostly Sunni and concentrated in the North) or overreacting, thereby creating incentives for individuals to join extremist groups,28 and bringing about a situation comparable to that which led to the rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria.29

The second debate pertains to the local drivers of the Islamist insurgency and the motives of those who have joined militant groups, whether due to socio-economic grievances or more political and ideological motives. Poverty, unemployment, social exclusion, and lack of access to basic services (education and healthcare) have been identified as key drivers of youth radicalisation in Cabo Delgado, as well as the Mwani people’s feelings of resentment towards the Makonde.30

The third debate concerns the extent to which the insurgency is domestically rooted or the result of transnational jihadism spreading south, given that the centre of gravity for violent extremism in East Africa is extending from Somalia southward to Kenya – as demonstrated by the Westgate, Garissa and DusitD2 attacks – and with Tanzania now as an emerging theatre.31 Although insurgents in Cabo Delgado are locally designated as ‘Al-Shabaab’, there are no signs that they are directly affiliated to the Somali extremist group, which has not made any public statement, or claimed any attacks in Cabo Delgado. That said, much of the leadership of the insurgents in Cabo Delgado allegedly has links with the religious circles of radical Islamist groups in Tanzania, Somalia, Kenya and the Great Lakes, as well as involvement in their commercial and military activities.32

Localised and multifaceted violence

Mozambique is also witnessing an increase in multi-layered, localised violence, manifest in different forms and characterised by different narratives and actors but sharing the common denominator of struggle against state authorities. Rumours of vampirism in Niassa and Zambezia provinces have led to violence, with local institutions and representatives of the state being attacked because they are believed to be part of a sect of ‘bloodsuckers’ preying on the people. Riots sparked by rumours of vampirism occurred in October 2017 in the Gilé district capital in the Zambezia province, and spread to neighbouring cities.33

The alienation of the country’s marginalised and disenfranchised youth is an incubator for violence in Mozambique. Young Mozambicans (45% of the Mozambican population is under 15 years old, while one third of the total population is aged between 15-35 years old) living in rural areas are increasingly alienated from their own cultural roots and traditions, while exposed to trends and images emanating from other parts of the world, dangling the prospect of a better future before them. This leads to profound frustration among these young people and increases their sense of marginalisation and powerlessness, leading them to resort to violence and organised crime. In the Niassa reserve and the Limpopo National Park, young people earn their livelihood by engaging in illicit cross-border trade in rhino horn, driven by hunger and lack of money.34 Urban youths are also inclined to engage in violence against the state, which they see as responsible for their social and economic distress.35

Recent data on economic and social transformation make bleak reading. 60% of Mozambicans were living on less than one dollar a day in 2018.26 Cuts in welfare expenditure, combined with large chunks of the public budget allocated to defence spending and debt servicing in the Planos Economicos e Sociais since 2015, have been widely criticised by civil society. The number of people entering the labour market each year is higher than the number of job opportunities available, and the unemployment rate in 2018 was 24.91%.27 The divide between urban and rural areas is also widening, especially in terms of service delivery: whereas in urban areas 80% of Mozambicans enjoy access to safe drinking water, only 35% of people in the countryside do; in terms of access to sanitation facilities, a similar divide may be observed between urban (with a 44% increase since 1990) and rural (11%) communities.38 The potential for violence in civil society, and especially among young people, is fomenting instability in Mozambique, which is now further exacerbated by the exploitation of natural resources in the north of the country.

The elephants in the room: natural gas and rubies

The north of Mozambique has become the epicentre for foreign direct investment as companies vie to extract its wealth of untapped natural resources. The discovery in 2010 of one of the world’s largest concentrations of natural gas has meant that resource extraction is now at the heart of Mozambique’s economic development, but also poses challenges as to how these revenues (expected from 2021 onwards) are going to be used, by whom, and with what risks in terms of competition among political and ethnic groups. The International Energy Association (IEA) estimates that Mozambique possesses 3 trillion cubic metres in natural gas reserves, located primarily in the Rovuma Basin area, prompting $100 billion investments by foreign companies (inter alia, ENI, Anadarko and Shell) and potentially making the country the third-largest exporter of Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) in the world.

Similarly, the discovery of the world’s largest ruby deposits in the Montepuez district in Cabo Delgado in 2009 had major repercussions for the world’s ruby market. Mozambique now accounts for 80% of the world’s ruby production. The Montepuez Ruby Mining company (in which Gemsfield owns a 75% stake), which was granted a concession covering an area of 340 km2, has earned over $400 million from international auctions since starting its operations in 2012.

The risks for conflict posed by the exploitation of natural resources unfold in many ways.39 The most salient one is the threat the insurgents may pose to the LNG investments off the coast. In addition, there is a danger that the country’s natural gas revenues may be siphoned off by corruption and mismanagement, thereby causing rising poverty and inequality, preventing growth from trickling down to the poorest communities, hence exacerbating social tensions.40 Rubies are also a dangerous business. In the past five years, more than half the revenue pouring into the state coffers in the province of Cabo Delgado came from taxes associated with exploitation of the ruby fields. Small producers and artisanal miners make up 90% of the industry and since the discovery of the ruby fields, nearly 10,000 people have come to northern Mozambique ‘digging and trading rubies, or offering goods and services to those doing the mining’.41 Mozambique’s ruby industry is now set to boom further as Fura Gems acquired licences between 2017 and 2018 for exploring up to 1,100 km2 in Montepuez and the Chiure District of Cabo Delgado. There is a risk that claims of human rights violations associated with multinational corporations could create grievances among the local population, making artisanal miners vulnerable to recruitment by Islamic insurgents. Members of the Cabo Delgado insurgency have reportedly become involved in the illegal mining trade and in smuggling (of licit and illicit goods). Unlike the LNG gas industry, gems can be extracted locally and insurgents can thus more easily forge links with existing criminal networks.42

Preventing conflict in Mozambique: what can be done?

Mozambique has experienced a shift in conflict dynamics from the long-standing confrontation between RENAMO and FRELIMO, to a more complex constellation of multifaceted and localised violence, against the backdrop of changing macro-economic risks, a widening rift between elites and the population, and new security threats, which introduce new layers of destabilisation. Because of the scale and implications of these transformations, a ‘pivot’ to conflict prevention in foreign assistance is recommended. What can international actors do to prevent the situation from deteriorating, and to foster positive transformation?

First, it is important to realise that the ‘prevention window’ will not remain open indefinitely. Timely action is of the essence. A pivot to prevention in Mozambique may lead to quickly re-orienting or adjusting international support towards more targeted conflict-prevention objectives. This reorientation will need to balance the need for conflict sensitivity with the imperative of effective and timely interventions for short-term relief and long-term recovery in the areas hit by Cyclone Idai. Mismanaged or sluggish post-disaster recovery efforts, combined with pre-existing social grievances, would create a ‘storm after the storm’ scenario in Mozambique, exacerbating conflict drivers.

In addition to effective disaster-risk management and resilience initiatives, which go beyond the scope of this article, a three-pronged approach can help maintain stability in Mozambique:

In the short term, strengthened electoral support could be provided ahead of the October 2019 general elections. Electoral fraud in Marromeu fuelled mistrust between FRELIMO and RENAMO, and alerted the international community to the possibility of larger-scale fraud and political violence during the presidential elections, indicating a need to step up long-term electoral support. Without concrete measures to rebuild trust between the two parties, especially on DDR, the likelihood of a relapse into violence during and after the election will increase. Multilateral actors and bilateral donors could beef up engagement in the full electoral cycle, beyond targeted election monitoring, stepping up commitment and conveying political messages to leaders to ensure the transparency and integrity of the electoral process, avoid violent mobilisation and any escalation of rhetoric in the electoral debate, so as to prevent contestation and the eruption of violence on and after election day. The credibility of electoral processes is critical for the future of the peace process, as the results of the elections and the way in which the polls are conducted in Mozambique will influence the sustainability of the peace agreement, also given the fact that this will be the first practical test for the 2018 constitutional amendments.

In the medium-term, an emphasis on conflict sensitivity and a more selective approach to investing in critical development projects could lead donors to target those areas where assistance can have most impact in preventing conflict. The EU is a case in point, being one of the leading aid donors in Mozambique, where EU institutions and the member states combined provided $570 million out of $1,532 million in 2016. The 11th European Development Fund (EDF) National Indicative Programme for Mozambique (2014-2020) amounts to €734 million.43 It prioritises rural development in the Zambezia and Nampula provinces (€325 million) and good governance and development (€367 million). Nearly half of the envelope (€300 million) is general budget support, but disbursements ceased following the illicit loans scandal in 2016. A prevention approach could identify sectors and geographical areas where assistance can produce immediate results in addressing social grievances. Three EU projects in Cabo Delgado, financed through the Development Cooperation Instruments and amounting to approximately €2.4 million, go some way towards this, by supporting civil society and local authorities to play a bigger role in development strategies. Addressing the needs of the artisanal mining communities could in fact mitigate the risks of conflict and mobilisation, as long as the instruments are reoriented towards a specific approach aimed at preventing violent extremism, by expanding communities’ access to licit economic opportunities.

Another area where action is crucial is vis-à-vis the youth of the country. As this Brief has shown, discontent is rife among Mozambique’s young people, particularly those living in rural areas and in the peripheries of urban centres, with many on the point of rebellion. Development assistance could prioritise projects addressing the integration of Mozambican youth into a sustainable social and economic growth path, reducing the sense of alienation and powerlessness that drives violence: promoting cultural activities for young people in urban areas, for instance, can help recreate a sense of purpose and mitigate the risk of them becoming involved in illicit trafficking and urban violence, and provide them with an incentive and role in building a new society.

In the long-term, foreign trade and political influence may support top-down wealth redistribution, inclusivity and the fight against inequality in Mozambique. This is particularly important in view of the gas boom. Mozambique’s extractive-driven economy has the potential to bring greater prosperity to the country, allowing for expansionary macroeconomic policies with catalytic effects on the growth of the services sector, hence contributing to the reduction of the poverty rate. At the same time, economic growth has fostered greater inequality between rich and poor, urban and rural areas, and the south and north of Mozambique, and the country still ranks among the most unequal ones in Sub-Saharan Africa.44 It thus cannot be assumed that the exploitation of Mozambique’s natural resources will inevitably or automatically bring prosperity and stability. The latter outcome will depend on how efficiently the central government commits to implement wealth redistribution, and the support the international community (and the EU) can provide to mitigate four risks: (i) the adverse effects of an extractive-driven economy on macroeconomic stability, especially in the absence of effective fiscal management; (ii) the potential role of extractive industries as a source of direct or indirect financing for the Islamist insurgency; (iii) grievances triggered by unmet expectations concerning natural resource windfalls, especially insofar as the absence of job creation and economic opportunities may be exploited by extremist groups for recruitment; (iv) the impact of the extractive industry on the political settlement in the country, as rent opportunities will likely affect the distribution of power within and outside the ruling elite. As a major political and trade actor in Mozambique,45 the EU’s contribution to risk mitigation and support to the government can be significant, for instance by scaling up assistance on fiscal management and wealth redistribution.

In conflict prevention, failure is far easier to measure then success. Actors have few political rewards for implementing a good conflict-prevention strategy, and must face very high transaction costs to sustain robust multilateral initiatives.46 Despite the lack of incentives, the international community is increasingly acknowledging the impact of prevention in securing long-term gains. In this regard, Mozambique is a test case for renewed international thinking and focus on conflict prevention: failure would turn the country into a hotspot of instability, whereas success could usher in a second era of shared prosperity, potentially creating a model for sustainable resilience and peace maintenance.

References

* The Brief was written with research assistance and valuable contributions from Ard Vogelsang (Trainee, EUISS). Fieldwork research for this Brief was carried out in Maputo, December 11-16, 2018.

1) World Bank national accounts data, annual GDP growth, https://data.worldbank.org/.

2) Anna Maria Gentili, “Lessons Learned from the Mozambican Peace Process”, IAI Working Papers no. 13-04, Istituto Affari Internazionali, Rome, January 2013.

3) Club of Mozambique, "Hidden Debts Timeline: From Loans’ Disclosure to Chang’s Arrest", January 19, 2019, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/hidden-debts-timeline-from-loans-disc….

4) Deloitte, Mozambique Economic Update: Resilience on the Path to Improvement, November 2017, p. 3, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/za/Documents/africa/Delo….

5) Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI), BTI 2018 Country Report – Mozambique, Gutersloh, 2018, pp. 30-31.

6) “Cyclone Idai: How the Storm Tore into Southern Africa”, BBC News, March 22, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-47638696.

7) World Bank and United Nations, Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict, 2018, Executive Summary, p. xi.

8) For a detailed account of the external and internal factors leading to the RENAMO insurgency and the Mozambican civil war, see Baxter Tavuyanago, “RENAMO: From Military Confrontation to Peaceful Democratic Engagement, 1976-2009”, African Journal of Political Science and International Relations, vol. 5, no. 1, January 2011, pp. 42-51.

9) World Peace Foundation, “Mass Atrocity Endings”, 2015, https://sites.tufts.edu/atrocityendings/2015/08/07/mozambique-civil-war/.

10) On post-war DDR process and reconciliation, and implications on the 2013 insurgency, see: Alex Vines, “Afonso Dhlakama and RENAMO’s Return to Armed Conflict since 2013: the Politics of Reintegration in Mozambique”, in Warlord Democrats in Africa: Ex-Military Leaders and Electoral Politics, ed. Anders Themnér (London: Zed Books, 2017); Stephanie Regalia, “The Resurgence of Conflict in Mozambique: Ghosts from the Past and Brakes to Peaceful Democracy”, IFRI Note no. 14, Institut français des relations internationales, 2017; Gary Littlejohn, “Secret Stockpiles: Arms Caches and Disarmament Efforts in Mozambique”, Working Paper of the Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, 2015.

11) Littlejohn, “Secret Stockpiles”, p. 22.

12) Ibid., p. 35.

13) On decentralisation, see: Roberta Holanda Maschietto, “Decentralisation and Local Governance in Mozambique: the Challenges of Promoting Bottom-up Dynamics from the Top Down”, Conflict, Security and Development, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 103-23.

14) For an in-depth analysis, see: Vines, “Afonso Dhlakama and RENAMO’s Return to Armed Conflict since 2013”, pp.121-56.

15) Club of Mozambique, "Nyusi Appoints 'Contact Group' for Peace Talks", March 2, 2017, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/nyusi-appoints-contact-group-peace-ta….

16) For details of the constitutional amendments and the implications on decentralisation, see: Karl Kossler, "Conflict and Decentralization in Mozambique: the Challenges of Implementation", ConstitutionNet, International IDEA, December 20, 2018, http://constitutionnet.org/news/conflict-and-decentralization-mozambiqu….

17) See: AllAfrica, “Mozambique: Government and Renamo Sign Memorandum on Military Issues,” August 7, 2018, https://allafrica.com/stories/201808100615.html.

18) Fieldwork interview, Maputo, December 2018.

19) Fieldwork interview, Maputo, December 2018.

20) Club of Mozambique, "Marromeu: Gross Illegalities in Rerun Election", November 23, 2018, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/marromeu-gross-illegalities-in-rerun-….

21) Fieldwork interview, Maputo, December 2018.

22) Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED), “Mozambique Update”, 2018, https://www.acleddata.com/2018/07/21/mozambique-update/.

23) Meetings of the author during fieldwork research in Maputo, December 2018. Evidence is also gathered from: Saide Habibe, Salvador Forquilha and Joao Pereira, “Radicalização Islâmica no Norte de Moçambique: O Caso da Mocímboa da Praia”, Working Paper, May 2018, http://www.open.ac.uk/technology/mozambique/sites/www.open.ac.uk.techno…; as well as from the H-Luso-Africa forum: https://networks.h-net.org/node/7926/discussions/1950075/recent-publica….

24) Ibid.

25) Club of Mozambique, "President Nyusi Warns that Cabo Delgado Terrorists 'Can Spread to Other Neighbouring Countries'”, September 26, 2018, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/president-nyusi-warns-that-cabo-delga….

26) Eric Morier-Genoud, “Mozambique’s Own Version of Boko Haram is Tightening its Deadly Grip”, The Conversation, June 11, 2018, https://theconversation.com/mozambiques-own-version-of-boko-haram-is-ti….

27) Club of Mozambique, "Mozambique: Six Mosques Reopened, Seven 'Actually Destroyed' in Cabo Delgado", May 28, 2018, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-six-mosques-reopened-seven….

28) UNDP, Journey to Extremism in Africa: Drivers, Incentives and the Tipping Point for Recruitment, 2017, pp. 73-74, http://journey-to-extremism.undp.org/.

29) See: Chatham House, "Democracy and Economic Inclusion in Mozambique: Understanding Prospects in the Context of the Past”, June 2018, https://www.chathamhouse.org/event/democracy-and-economic-inclusion-moz….

30) Fieldwork interview, Maputo, December 2018.

31) International Crisis Group, "Al-Shabaab Five Years after Westgate: Still a Menace in East Africa", Report no. 265, September 21, 2018.

32) On the ties between the insurgency in Cabo Delgado and international jihadism, see: Gregory Pirio, Robert Pittelli and Yussuf Adam, The Emergence of Violent Extremism in Northern Mozambique, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 2018, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/the-emergence-of-violent-extremism-i….

33) Examples of localised violence are gathered from a conversation with Bernhard Weimer in Maputo, and from his work on violent manifestations of local discontent in Mozambique and implications for peacebuilding.

34) Ibid.

35) Ibid.

36) BTI 2018 Country Report - Mozambique, p. 20.

37) World Bank data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=MZ.

38) Ibid, p. 8.

39) See: Alex Porter, David Bohl, Stellah Kwasi, Zachary Donnenfeld and Jakkie Cilliers, “Can Natural Gas Improve Mozambique’s Development?”, Southern Africa Report no. 10, Institute for Security Studies and Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, September 2017.

40) Ibid, p. 33.

41) Matthew Hill and Borges Nhamire, “Mozambique’s Ruby Mining Goes From ‘Wild West’ to Big Business,” Bloomberg, August 13, 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-08-13/mozambique-s-ruby-mi….

42) Simone Haysom, "Where Crime Compounds Conflict: Understanding Northern Mozambique’s Vulnerabilities", The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime, October 2018, p. 21.

43) European Union – Republic of Mozambique National Indicative Programme 2014-2020, Signed in Brussels on 26 November 2015.

44) Mozambique’s Gini coefficient has increased from o.47 to 0.56 between 2008 and 2014. The four northernmost provinces, including Cabo Delgado, have the highest poverty rate. See World Bank, Mozambique Economic Update: Shifting to More Inclusive Growth, October 2018, pp. 25-26, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/132691540307793162/pdf/131212….

45) In 2017, Mozambique exported almost €5 billion in goods worldwide of which 32% went to the EU-28, making it the largest export destination. Mozambique’s trade flows to the EU in 2017 were €1,664 million in value and predominantly consisted of fuels and mining products (€1,387 million or 83.3%)

46) See: Katy Collin, The Year in Failed Conflict Prevention, Brookings Institution, December 14, 2017.