You are here

Bosnia and Herzegovina's quest for EU membership

Introduction

‘The Commission recommends opening of accession negotiations with Bosnia and Herzegovina once the necessary degree of compliance with the membership criteria is achieved’: so reads the 2023 Enlargement Package unveiled on 8 November. Ahead of the European Council in December, some EU Member States might still argue that December 2023 is the moment to reach the milestone, while others will recall the requirement to fulfil 14 key priorities identified in the European Commission’s 2019 Opinion on Bosnia and Herzegovina’s (BiH) application for EU membership before opening negotiation chapters.

Particularly important are the Opinion’s priorities which require comprehensive reforms, such as reform of the Constitutional Court and of the judicial system, including the High Judicial and Prosecutorial Council (HJPC), and electoral reforms to address the ruling by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in the case of Sejdic and Finci v. BiH (2009). The Court found the BiH system discriminatory as only persons belonging to ‘constituent peoples’ (1) are entitled to run for the House of Peoples (upper House of Parliament) and tripartite presidency. This setup is a direct outcome of the Dayton Peace Agreement (DPA), signed between the warring parties in 1995 to put an end to the violent conflict, thus laying the foundations for a peaceful and democratic country.

Fast-forwarding to 2023, BiH remains far from being a multi-ethnic country where the rights of individuals are exercised equally, as confirmed by a series of ECHR rulings – Kovačević (2023), Pudarić (2020), Pilav (2016), and Zornić (2014). Rather than establishing a consociational model of functional multi-layered governance, the DPA provided ethno-nationalist elites with constitutional means to consolidate their grip over institutions (and resources), resulting in nearly three decades of political and institutional deadlock.

This Brief argues that instead of abolishing the DPA in its entirety, the EU ought to centre its policy on making the Dayton Accords more functional via structural reforms, without redefining borders and making new territorial provisions. This does not preclude assessing the potential of popular pressure for alternative modes of governance, but in the meantime the Dayton rules need to be enforced. It is too idealistic to believe that an alternate system of governance would work at present as the main elements that make the arrangements created by the DPA so complex remain in place.

The Dayton Peace Agreement: Not fit for purpose?

The country is facing a twofold challenge: First, at the state level, BiH operates under a complex and inefficient decision-making system underpinned by a discriminatory constitution and electoral law, with little to no independence and impartiality of the judiciary. The latest and most far-reaching of the ECHR cases, Kovacevic v. BiH (2023), confirmed that this electoral and political system undermines democratic principles. Not only does it deny the right of citizens not belonging to ‘constituent peoples’ to stand for elections, but also voters residing in Republika Srpska are entitled to vote only for Serb candidates in presidential elections, while voters in the Federation of BiH can vote for either the Croat or Bosniak candidate. Therefore, if a person is not from the ‘right entity’ or is not of the ‘right ethnicity’, they cannot vote for their preferred candidate.

Furthermore, current institutional arrangements are thwarting the country’s socio-economic growth. BiH’s level of GDP per capita in 2023 is roughly one fifth of that of the EU (€7,110 v. €37,590) (2). Ethno-nationalistic divisions with attendant abuses of power and corruption are also leaving citizens more and more disillusioned. In the space of ten years (2012-2022), the corruption perception index ranking fell from 42 to 34, which represents the steepest decline in the Western Balkans and is the third worst in Europe (3). This has propelled popular distrust in institutions that increased within a range of 10 percentage points between 2019 and 2022 (see graph opposite). As a result, estimates indicate that between 2013 and 2020, BiH lost more than 7 % of its population, which translates into 25 000 inhabitants emigrating on an annual basis (4).

Practitioners in the field often contend that the only way to get things done is by engaging directly with the entities. With exclusive competencies assigned to entities and cantons, the legitimacy of the central government is limited and constantly challenged by ethnic leaders’ quest for greater control. The near-permanent state of institutional and political gridlock highlights the need for alternative modes of governance that go beyond inter-ethnic territorial divisions. One potential solution to consider is that of a two-layered state structure with a strong government and parliament (state level) and municipalities with exclusive competencies (municipal level) that currently rest with entities and cantons. The ‘municipalisation model’ (5) foresees a simplified BiH governance system, where citizens vote for individuals, not parties, while each municipality elects its representatives directly to the National Assembly. This model guarantees legal and social equality to all citizens, without supremacy of ‘constituent peoples’. Whatever the change, it must come from within society and first and foremost ensure citizens’ buy-in. The experience of the past 28 years shows that externally imposed solutions are short-sighted and do not produce long-lasting societal change.

Data: Regional Cooperation Council, Balkan Barometer, 2019-2022

The second challenge lies at the entity level, where consolidation of power in the hands of ethno-nationalistic parties continues to block any attempts to reform and bring the country forward, including towards the EU. One need look no further than Republika Srpska under President Dodik for an illustration of this dynamic. Two controversial laws were adopted in 2023 (the ‘Law on the Non-application of Decisions of the BiH Constitutional Court in Republika Srpska’ and amendments to the ‘Law on Publication of Laws and Other Regulations’) which seriously undermine the authority of the BiH government and of the Office of the High Representative (OHR), an ad hoc institution established by the DPA and tasked with overseeing the implementation of civilian aspects of the agreement. In December 2022, the OHR suspended the controversial ‘Law on Immovable Property’ in Republika Srpska aimed at transferring ownership of agricultural land, forests, and rivers from state to the entity level (6). Milorad Dodik vowed to defy the OHR’s decision and enforce the law. This led to the Prosecutor’s Office of BiH filing an indictment against Milorad Dodik in August 2023.

In response to the indictment, since September 2023 hundreds of Bosnian Serbs have been staging protests under the slogan ‘The Border Exists’ in support of Milorad Dodik, waving Russian and Republika Srpska flags bearing the image of Vladimir Putin. The Kremlin’s influence and long-established support for this BiH entity leadership’s divisive narrative serves both Moscow and Banja Luka well. Russia will now want to step up its support, given the global polarisation amplified by the wars in Ukraine and Gaza.

Data: Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2023; Republic of Srpska Institute of Statistics, 2023

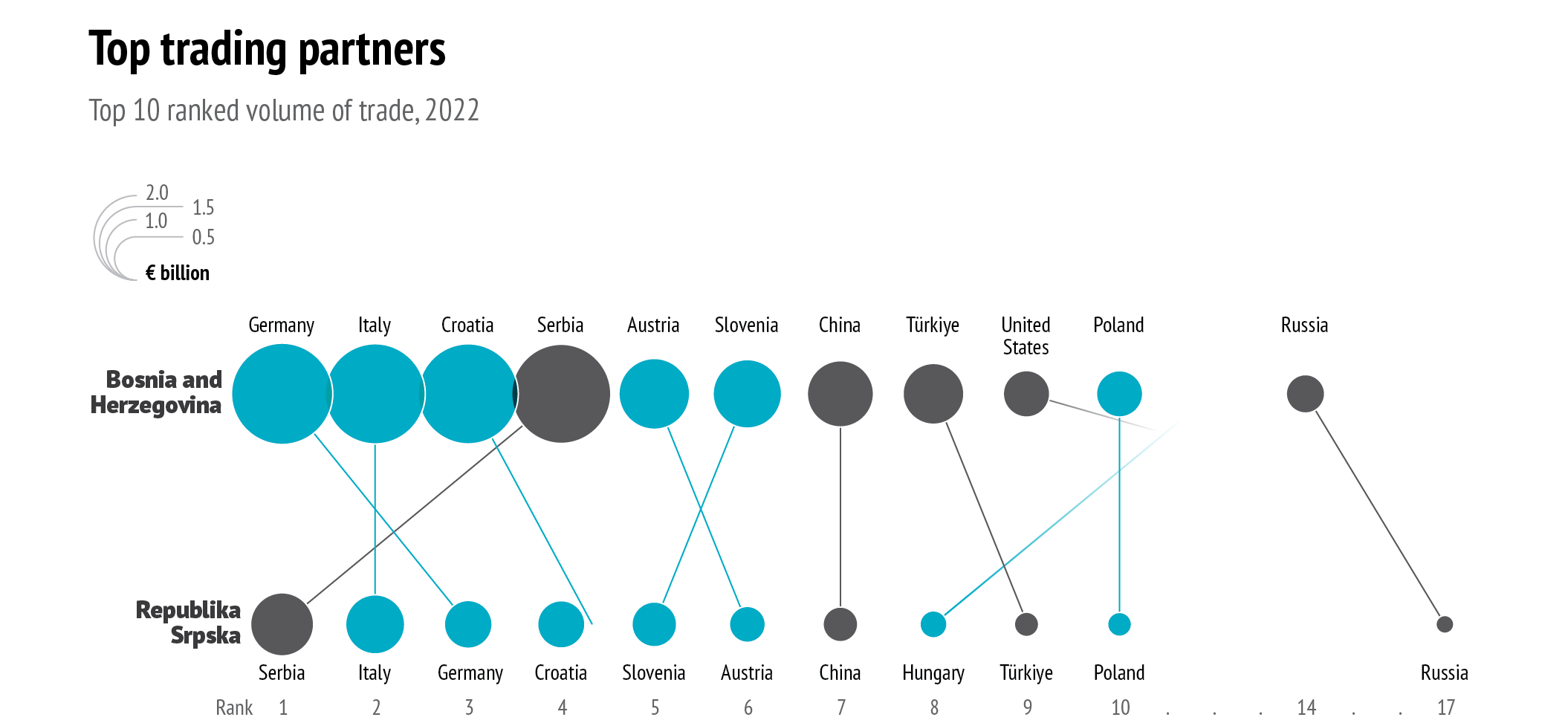

Since the start of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, President Dodik has met Putin three times, more frequently than any other leader in Europe. While ideologically the two leaders seem to be on the same wavelength, economic indicators tell a different story: Russia did not even feature among the 15 top trade partners of Republika Srpska in 2022; meanwhile, EU Member States together account for more than 60 % of total trade. The same scenario can be observed at the state level, where the figure for the EU stands at 63.3 % (see diagram opposite).

Changing the dynamic

Stark reality casts a shadow ahead of the European Council meeting of 14-15 December. Even if the Council chooses to ignore the Commission’s recommendation and opens accession negotiations, the main structural complexities that hobble the country remain. The citizens may welcome the prospect of EU membership, but in the long run it will make no actual difference as BiH institutions still need to undertake the necessary reforms. EU membership is not a miracle solution to the country’s problems but rather an incentive to get the country moving in the right direction.

Citizens themselves should campaign for institutional change and if necessary a fundamental overhaul of the Dayton constitutional framework. With parties in power benefiting from the status quo, changes to the constitution are highly unlikely to happen if not pushed from within. The EU should find a better way to communicate with citizens and foster a bottom-up approach in engaging with civil society and local actors on the ground. This could be done through targeted campaigns on enhancing transparency, building confidence, and raising awareness of EU activities. Applied conditionality in the EU accession process will not in itself be sufficient to extricate the country from the dysfunctionalities of the current tripartite power-sharing system. Initiating a broader societal dialogue on the need for judicial, electoral and constitutional reforms would give more power to local voices across entity borders to demand stronger engagement of governing elites.

The EU should condition the accession upon fulfilment of the 14 key priorities based on a ‘fundamentals first’ approach. With the new Growth Plan, EU financial assistance is strictly conditioned and proportional to delivering on the fundamentals. The latter concern, among other matters, modernisation of the judiciary, including the amendments to the law on the HJPC and discriminatory electoral system that needs to be reformed in line with ECHR rulings. The EU should consider establishing a joint European Commission-BiH-European Parliament working group on the implementation of electoral and constitutional reforms. In this way, a new mechanism would be created to engage directly with citizens through sortition (7) (through the establishment of a ‘Citizens Assembly’) and tap into the popular demand for change, as rule of law remains a significant concern.

The legitimacy of the central government is limited and constantly challenged by ethnic leaders’ quest for greater control.

The EU should invest more diplomatic efforts in articulating a coherent policy vis-à-vis BiH. This particularly concerns the imposition of sanctions on Milorad Dodik for his repeated secessionist activities. The EU’s inability to impose sanctions sends mixed signals and only further emboldens Milorad Dodik. While it is too idealistic to expect EU Member States to reach an agreement anytime soon, the Member States could proceed individually, following in the footsteps of Germany which recently decided to suspend four strategic infrastructural projects in Republika Srpska worth € 105 million (8). The EU and its partners should unequivocally condemn any attempts to denounce or challenge the current constitutional order.

The EU should invest more diplomatic efforts in articulating a coherent policy vis-à-vis BiH.

The EU should consider initiating a permanent policy dialogue between EU Member States and BiH authorities with the aim of policy learning and sharing of experiences. Particularly relevant in this regard is the Belgian experience in administering relations between federal government, regions and communities, including in matters of transfer of exclusive competencies and non-territorial autonomy. Belgium has a strong central level of government with power-sharing mechanisms designed in a way that does not threaten the autonomy of the regions/communities while still retaining a number of institutions with nationwide reach. The model of non-territorial autonomy on the other hand, grants different linguistic groups a degree of local autonomy in matters of education, culture and language use and provides for power-sharing mechanisms through Flemish and French Commissions for community matters (9). This approach could facilitate better integration of ethnic minorities across entities (Bosniaks/Croats in Republika Srpska and Serbs in the Federation of BiH).

Finally, the EU needs to find the right balance between stability and democracy. Today BiH is far removed from the environment of heightened insecurity of the 1990s; it is surrounded by NATO members to the north-west (Croatia) and south-east (Montenegro), with EUFOR Operation Althea on the ground. The country needs no new tools or mandates to ensure security. What it does need however is political will. Prioritising ‘stabilitocracy’ over fundamentals keeps the country under the tight grip of ethno-nationalist elites and does little to improve central governance. It is therefore unfortunately to be expected that ideological fractures may prevent BiH from getting the necessary EU homework done. Against this backdrop, it will be important for the EU to insist on the crucial importance of fundamentals to ensure that the progress towards EU integration is not derailed by nationalist divisions.

References

1. ‘Constituent peoples’ are persons who declare affiliation with Bosniaks, Serbs or Croats, as opposed to ‘Others’ who belong to minorities, including persons who do not declare their affiliation with any group.

2. International Monetary Fund, ‘GDP per capita, current prices U.S. dollars per capita’, 2023 (https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDPDPC@ WEO/BIH/EU).

3. A country’s score is the perceived level of public sector corruption on a scale of 0-100, where 0 means ‘highly corrupt’ and 100 means ‘very clean’. See Transparency International, ‘Corruption Perceptions Index’, 2022 (www.transparency.org/index/bih).

4. UNFPA and Czech Republic Development Cooperation, The Effects of Population Changes on the Provision of Public Services in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2022 (unfpa.org/pdf/effects_of_population_changes.pdf).

5. The municipalisation model stems from an idea proposed by several mayors in BiH which was structurally and functionally developed further by the Democratization Policy Council (DPC), Kurt Bassuener and Bodo Weber. (For more on this see: https://municipalizacija.ba/).

6. See DPC, ‘Peace dividend: What the discussion about state property in Bosnia and Herzegovina really means’, DPC Policy Note 18, 24 July 2023 (http://www.democratizationpolicy.org/peace-dividend/).

7. Sortition is a process of randomly selecting a demographically and geographically representative group of citizens to debate on matters of public or political interest. For more on sortition, see BertelsmannStiftung, ‘Citizens’ participation using sortition’, June 2018 (https://aei. pitt.edu/102678/1/181102_Citizens Participation_Using_Sortition_ mb_-_Copy.pdf) and for an Irish example, see Democracy International, ‘The Irish referendum on abortion: a feat of direct democracy?’, 2018 (https://www.democracy-international.org/irish-referendum-abortion- feat-direct-democracy).

8. See European Western Balkans (EWB), ‘Sarrazin: 4 German projects in RS suspended due to Dodik’s secessionist policy’, 7 September 2023 (europeanwesternbalkans.com/2023/09/07/sarrazin-four-german- projects-in-rs-suspended/).

9. See Dalle Mulle, E., ‘Belgium and the Brussels question: The role of non-territorial autonomy, Ethnopolitics, Vol. 15, No 1, 2016 (www.tandfonline. com/doi/abs/10.1080/17449057.2015.1101839).