You are here

Under pressure: can Belarus resist Russian coercion?

Introduction

Belarus is traditionally considered to be Russia’s closest ally, and their alliance is a cornerstone of post-Soviet integration projects, both military (the Collective Security Treaty Organisation - CSTO) and economic (the Eurasian Economic Union - EAEU). But bilateral relations have entered a different and more conflictual phase. The paradigm shift started in 2014, when Belarus invoked its constitutional neutrality pledge to refuse to side with Russia in its ongoing conflict with Ukraine and the West. Playing this card allowed President Lukashenka to appear as a security guarantor both in the eyes of Belarusians and the West. Irritated by such autonomy, Moscow indicated that it now wants more for its money.

Russia is no longer ready to subsidise the Belarusian economy in exchange for its neighbour’s fleeting geopolitical loyalty. In linking, in 2018, the resumption of economic privileges to ‘deeper’ political integration within the Union State that the two countries nominally established 20 years ago, Russia stepped up the pressure. Yet Vladimir Putin made Belarus an offer he knew Aliaksandr Lukashenka would refuse: the Belarusian president had repeatedly stated that Belarus’s sovereignty was ‘not for sale’.

Given its dependence on Russia and current economic hardships, Belarus might not be able to resist Moscow’s ‘coercion to integrate’, however. Its capacity to uphold its sovereignty is being challenged from outside, while Lukashenka’s regime survival is under stress from within: in the wake of the 9 August presidential election, unprecedented opposition forces emerged which the Belarusian regime started cracking down on.1 Should repression intensify, leading the West to reintroduce sanctions, Minsk’s efforts of the past years towards normalising relations with Brussels and Washington would come to nothing. Yet renewed (self-)isolation of Belarus is exactly what Russia needs to reach its strategic goal of keeping Belarus in its orbit, and extract more concessions from its fragile leadership.

This presents the EU with a dilemma it knows all too well: how can it support Belarus’s efforts to preserve its independence, without increasing the resilience of Lukashenka’s authoritarian regime or making Russia more assertive?

Russia’s coercion to ‘deeper integration’

Whereas Russia’s relationship with Belarus was always marred by diplomatic disputes, blackmail and various ‘trade wars’, in recent months disagreements have shaken the very foundations of their strategic alliance. The paradigm change became obvious in late 2018, when Moscow stepped up pressure on Minsk to deliver on earlier commitments regarding the institutional ‘deepening’ of the Union State of Belarus and Russia.

Formally established two decades earlier as an intergovernmental project, the Union State should become, according to the Kremlin, a supranational organisation. Aware that it would be dominated by Russia given the imbalance between the two Union members, the Belarusian leadership has always resisted the idea of transferring elements of sovereignty to a would-be supranational body, however.

Throughout 2019 the two parties conducted intense negotiations on revising and updating the 1999 Treaty establishing the Union State,2 but they hit a wall by the end of the year.3 The bone of contention was the last three items of a list of 31 roadmaps which Belarus allegedly refused to even discuss since they provided for transferring prerogatives and elements of Belarusian sovereignty to the Union State in fiscal and monetary fields.

For Belarus the only incentive to integrate closer with Russia – be it within the Union State or the EAEU – is tied to expected benefits relating to the conditions and tariffs for purchasing Russian oil and gas. Discounts on hydrocarbon deliveries have always represented a major share of the Russian subsidies that keep Belarus’s unsustainable economy afloat (they represented up to 20% of Belarus’ GDP in 2006).4 In cutting subsidies down, Moscow is trying to force Minsk to accept either Russian re-integration plans or further ‘marketisation’ of their trade relationship, with the levelling up of tariffs towards world market prices.

The bargaining started when Russia modified the taxation regime of its oil exports, making purchasing Russian crude oil more costly for Belarus. Minsk demanded that the Russian budget compensate for its profit losses due to this ‘tax manoeuvre.5’ In December 2018, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev indicated that this and the resumption of subsidies in general was conditional upon Belarus agreeing to deeper integration within the Union State.6

Faced with Medvedev’s ultimatum, Lukashenka replied that Belarus’s sovereignty was ‘not for sale’: he rightly foresees that a supranational Union State would actually resemble an enlarged Russian Federation, entailing much less prerogatives for him personally. This dialogue of the deaf reached an impasse in late 2019.7 For failing to agree to political unification on Russia’s terms, Belarus is set to lose economically. The new status quo is not to its advantage and Belarus’s structural dependence on Russian hydrocarbons gives the Kremlin the upper hand in future negotiations.8

What Russia wants is Belarus’s geopolitical loyalty, which started evaporating after Russia’s 2008 war with Georgia.

Yet reviving the stillborn Union State might have been a mere pretext from the onset. Once again, Putin has backed Lukashenka into a corner by presenting him with an unacceptable option. In fact, what Putin is after is not a fool’s bargain on institutional integration. For almost two decades, Russia has tolerated Belarus’s eccentric conception of what being an ally means, and it too was satisfied with the Union State being a mere platonic union.

What Russia wants is Belarus’s geopolitical loyalty, which started evaporating after Russia’s 2008 war with Georgia, when President Lukashenka refused to recognise the independence of the breakaway republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. This earned him more consideration in the eyes of the EU, contributing to Brussels lifting some of its sanctions a couple of months later, and extending an invitation to Belarus to join the Eastern Partnership in 2009.

What Russia does not want is Belarus ever turning to the West and this is exactly what has been happening since 2015. Amid the emergence of the latest wave of Belarusian nationalism (aka ‘soft Belarusianisation’), which Lukashenka expediently seeks to exploit to rally his people around the flag,9 the autonomisation of Belarus’s foreign policy and its flirting with the West came to be seen as unacceptably anti-Russian.

Belarus’s survival strategy

In refusing to recognise the 2014 annexation of Crimea de jure, and by invoking the neutrality pledge enshrined in Belarus’s constitution to refuse to side with Russia in its ongoing conflict with Ukraine and the West, Lukashenka opted for sovereignty over loyalty. This raised considerable distrust in Moscow, especially after Belarus became involved in schemes bypassing the Russian embargo on food imports from the West, and on oil exports to Ukraine.

Lukashenka’s survival strategy always consisted of a balancing act, playing Russia against the West in order to extract benefits from both. Tactically, it relied on geopolitical blackmailing of Russia, threatening to seek a rapprochement with the EU to force Moscow to resume subsidising its economy. Lukashenka knows how to exploit Putin’s neo-imperialist syndrome, as illustrated in the row over establishing a Russian airbase on Belarusian territory, a demand repeatedly made by Russia since 2013. Eager to maintain good neighbourly relations with all its other neighbours, Lukashenka has consistently and, so far, successfully, rejected such security outsourcing.10 This, in turn, has allowed him to showcase himself in the West as the guarantor of Belarus’s sovereignty and a contributor to regional peace and stability.

In relation to Brussels, ‘dictaplomacy’ was always Lukashenka’s main regime-survival tool: turn a blind eye to my authoritarian wrongdoings, otherwise an isolated Belarus will fall back into Russia’s embrace, was his underlying message.

In hosting the peace talks that led to the Minsk agreements, Belarus bolstered its image as a ‘neutral buffer state’, further improving its rating in the West.11 Despite limited progress towards meeting the democratic conditions attached to Western sanctions, in 2016 the EU, later followed by the US, started gradually lifting coercive measures against the regime.

Diversifying international partnerships is Lukashenka’s key survival tactic. It endows Belarus’s notional ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy with some substance and has led to a number of breakthroughs which have bought Belarus time and diplomatic support in its quest for autonomy.

Lukashenka’s main regime-survival tool: turn a blind eye to my authoritarian wrongdoings, otherwise an isolated Belarus will fall back into Russia’s embrace.

The first breakthrough was the signing of a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership with China in 2013. This led to establishing an industrial park near Minsk and attracted some Chinese investments – albeit mostly as tied loans for now. Belarus also aspires to become a European hub for Xi Jinpin’s Silk Road Initiative. Cooperation accelerated following the Ukrainian crisis, notably in the military field: with Chinese support Belarus developed a multiple-rocket launcher, named Polonez, able to compete with Soviet and Russian artillery systems on world markets.12

Belarus’s diversification efforts yielded results on the Western front too, the most spectacular improvement being in relations with the United States. Minsk and Washington have been working towards mending their relationship since 2018. After sanctions were partially lifted, an agreement was struck regarding the return of a US ambassador to Belarus after a 12-year break. The ongoing thaw climaxed with the visit of Mike Pompeo to Minsk in February 2020, when the US Secretary of State announced that his country could supply Belarus ‘with 100 % of the oil it needs, at a competitive price’, to help it secure its sovereignty.13 Although such an import scheme sounds unsustainable, the message sent – to Minsk, and to Moscow – is groundbreaking.

The improvement of Belarus’s relations with the EU and several EU member states individually – notably Poland – has led to a de facto normalisation, albeit still without a framework agreement. The ongoing construction of a nuclear power plant in Astravets near Belarus’s border with Lithuania remains a fly in the ointment. Renewed dialogue reopened opportunities for cooperation, however. The most significant progress is the signing of a Visa Facilitation and Readmission Agreement in May 2020. As a result, the Schengen visa application process will be faster and the fee should drop to €35 for Belarusians.

Combined with the diversification of its foreign partnerships, the qualitative improvement in Minsk’s relations with potential trade partners helps Belarus counterbalance its economic dependence on Russia. The prospect of increased foreign direct investment (FDI), trade flows, and access to credits from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), motivates the Belarusian authorities to uphold this strategy – with the caveat that, due to the lack of structural reforms, they should not expect much from Western donors.

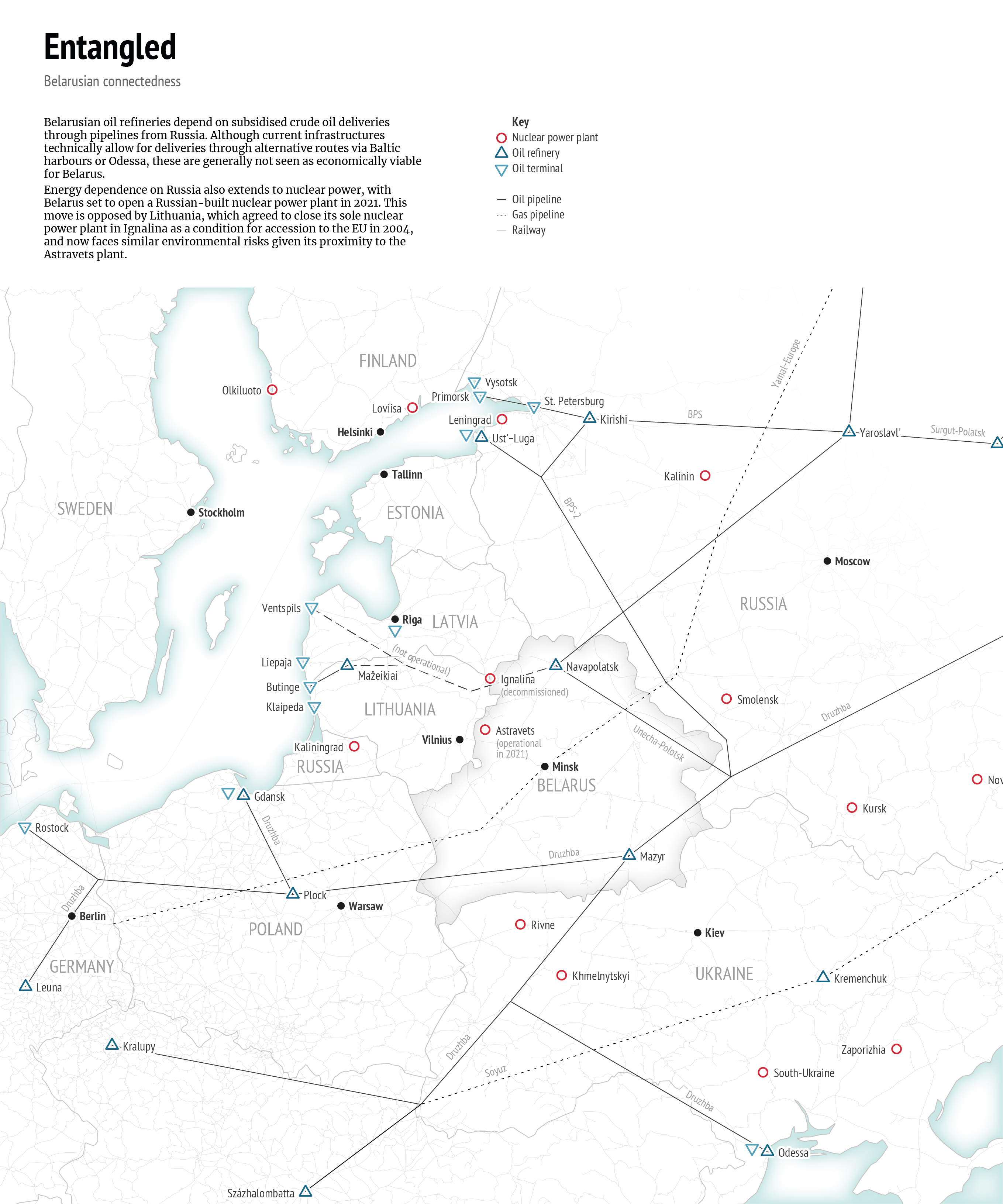

Lastly, Belarus has attempted to diversify its sources of energy, negotiating with potential oil suppliers (Norway, the US, Azerbaijan) and transit countries (Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia).14 The first shipment of a mix of US and Saudi oil was announced in May 2020. It will probably transit via the Ukrainian harbour of Odessa, since the railway connecting the Klaipeda oil terminal (in Lithuania) to Belarus is deemed to have insufficient capacity for handling the announced 600,000 barrels (about 80,000 tons).15 The investments required in multimodal transport infrastructure will have to be guaranteed in order for alternative routes to Russian pipelines to prove competitive in the long run.

Belarus’s structural dependence on Russian energy is unlikely to be overcome by a couple of overseas deliveries, however. Russia remains confident that Belarus’s levers in future negotiations are shrinking.16 ‘Gazprom diplomacy’ remains a powerful pressure tool, as the gas giant links its pricing policy to the repayment of Belarus’s debt.17 Moreover, Putin has a number of other tricks up his sleeve.

Data: Esperis.pl, 2020; World-nuclear.org, 2020; Gazprom.com, 2020; Eegas.com, 2013; Hydrocarbons-technology.com, 2020; Ecifpa.ru, 2020; Natural Earth, 2020

Vulnerabilities in the face of hybrid threats

In recent years Russia has activated various hybrid warfare tactics against Belarus. The aim is to influence domestic developments so as to constrain Lukashenka’s capacity to control domestic affairs and extract decisions that satisfy Russia’s geopolitical objectives.

Hybrid warfare uses coordinated military, political, economic, civilian and informational (MPECI) instruments of power that allow the pursuit of strategic goals below the threshold of traditional armed conflict. Russia used it extensively against Ukraine, as a complement to its unadmitted military intervention in Donbas. And it implemented non-linear ‘active measures’ (in Soviet jargon) elsewhere as well.

In the case of Belarus, hybrid threats emerged in 2015-2016 when Russia intensified its soft power or, rather, ‘sharp’ power projection.18 The effort initially targeted public opinion on Ukrainian issues to popularise the belief that Belarus was intrinsically part of the ‘Russian World’ (Russkij Mir).`19 Hence, the narrative went, Belarus was at risk of suffering the same fate as Ukraine – social unrest and a ‘fascist coup’ by ‘nationalists on a Western payroll’, followed by a ‘civil war’ – should a Colour Revolution occur. The subliminal message was that Russia could intervene militarily in that event.

Belarus is extremely vulnerable to Russian (dis)information because it is virtually integrated into the Russian infosphere.

This marked the beginning of a massive propaganda campaign in Belarus, later diagnosed as a ‘creeping assault’ on Belarusian sovereignty.20 Evidence accumulated that Russia was establishing a large-scale system of interference, using state-controlled, quasi-private and non-governmental initiatives, allegedly coordinated from the Kremlin.21 This system includes foundations, government-organised non-governmental organisations (GONGOs), the Russian Orthodox Church, sports clubs and even Cossack groups. Individually and as a network, these agents of influence form a potential fifth column in Belarus. For now their mission is to spread Russophile narratives and Russkij Mir worldviews, to deter popular aspirations to nation-building, and turn Russian and Belarusian public opinion against Lukashenka and his policies.

Belarus is extremely vulnerable to Russian (dis)information because it is virtually integrated into the Russian infosphere, with 60% of the content aired on TV actually produced in Russia. Pro-Kremlin propaganda is impactful because internet-connected Belarusians are increasingly getting information on socio-political, economic and foreign policy issues from social networks such as VKontakte (the Russian equivalent of Facebook), blogs and Telegram or YouTube channels, which are dominated by pro-Russian influencers and narratives.22

The Belarusian authorities’ response to Russian media interference has been too little, too late, to protect the country against such malign influence.23 The narrow media landscape, (self-)censorship and systematic restrictions on freedom of speech make alternative discourses inaudible. Having spurned the Belarusian language and the national culture for two decades, Lukashenka’s sudden metamorphosis into a nationalist looks unconvincing. Unless the government issues a 5-year plan supporting ‘soft Belarusianisation’ – which, for now, is mostly a spontaneous societal movement – bureaucrats and state-owned media will not develop pro-Belarusian messages able to compete with Russian propaganda.24 Lukashenka’s own personal survival strategy might not be sustainable in the face of Russian interference.

Weakening grip and increased risks

Of all Russia’s post-Soviet neighbours, Belarus is the most likely candidate to be subjected to the same treatment as Ukraine.25 Conventional force might not be necessary, however, for subjugating Belarus to the extent Russia needs for meeting its strategic goal of keeping the country under its control. Given that Vladimir Putin might again need a quick geopolitical victory to boost his own popularity ratings, a hybrid action or even a Crimean scenario to fully vassalise Belarus should not be excluded a priori.

This said, the Russian army lacks the means to sustain a long occupation of, or war of attrition in, Belarus. It might have infiltrated Belarusian civil society, and rely on pro-Russian siloviki, but existing fifth column elements are not sufficient to subjugate Belarus yet. The Belarusian military remain loyal to their country, and the population would not welcome absorption, whether achieved by force or by ruse.

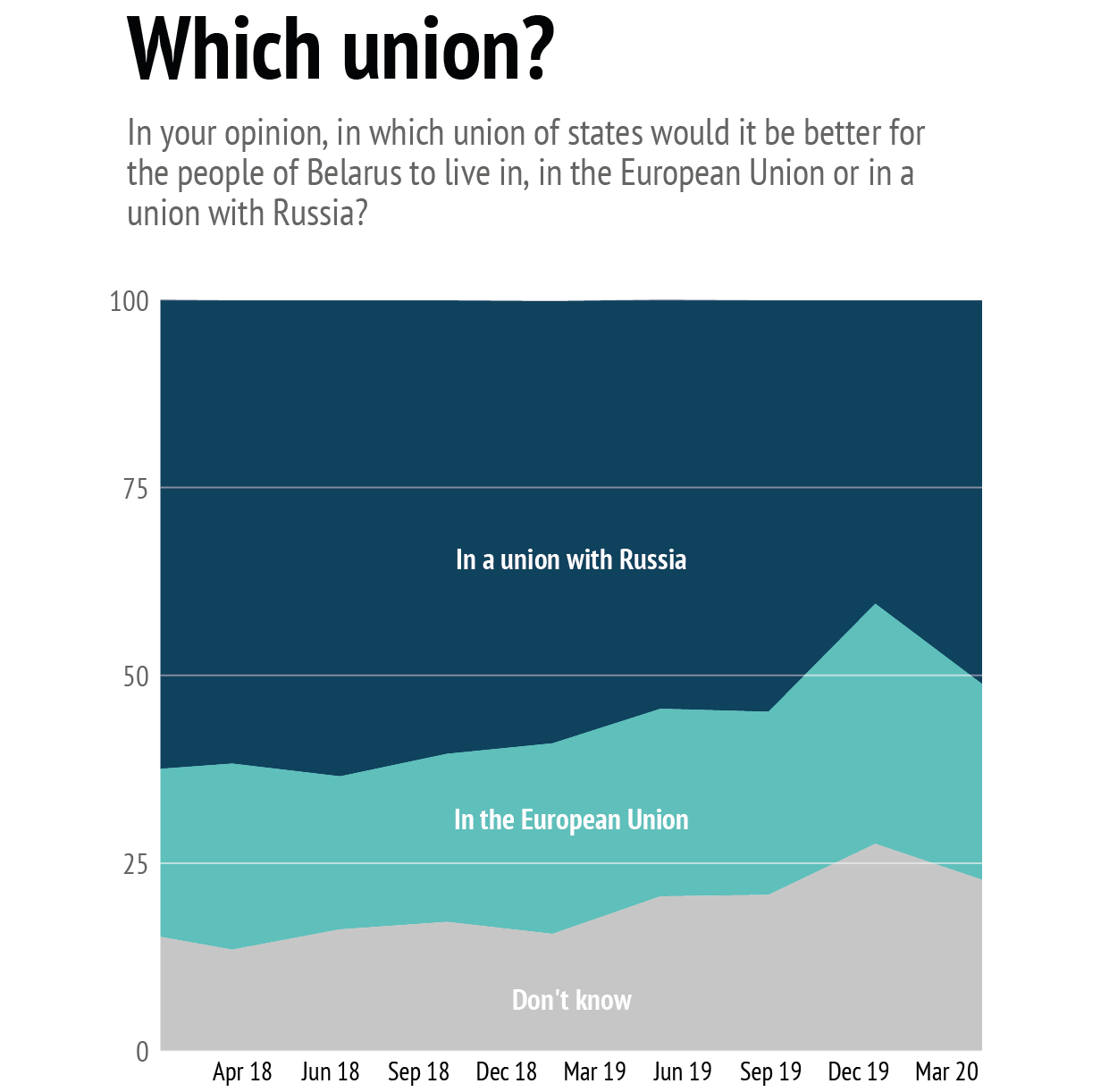

The prospect of Belarus becoming part of the Russian Federation – which Vladimir Putin indicated in 2002 was his favoured integration scenario26 – finds no support in Belarus (less than 1.4 % of the population, according to an August 2019 poll).27 If offered multiple options, the majority of Belarusians (43%) would prefer independence over a union with Russia (22%) or joining the EU (18%).28 Since 2014, sovereignty has grown even dearer to their heart, and support for uniting with Russia declined by 20 percentage points during the 2019 negotiations on ‘deeper integration’.

*Sample size: 1061 urban and rural Belarusians

Data: Andrey Vardomatsky,Belarusian Analytical Workshop, 2020

A tangible threat remains, however, that Russia uses sharp power tactics, and Gazprom diplomacy, to aggravate Belarus’s domestic hardships to extract concessions from Lukashenka. In 26 years, the Kremlin has learnt to accommodate itself to its eccentric partner, and toppling him was never a priority. But helping him stay in power makes less sense if whoever succeeds him has only Russia to turn to for economic support anyway.

In recent months Belarus’s situation has evolved from bad to worse and this creates new opportunities for Russia. Amid sharp economic decline and the Covid-19 crisis, Lukashenka appears as politically weakened for the first time during his reign.28 His trust capital and electoral rating have dropped in the eyes of a fast-changing Belarusian society.30

In May and June 2020, hundreds of thousands of Belarusians braved the risk of Covid-19 contamination to line up to give their signatures to citizen initiative groups nominating alternative candidates. Over 400 dissenters – political activists, human rights defenders, journalists, bloggers, etc. – were sentenced to fines or administrative detention for participating in ‘unauthorised mass events.’31 This followed the arrest of a famous blogger, Siarhei Tsikhanouski, who was touring the country to meet his followers, and launched the ‘get rid of cockroaches’ slogan – earning the movement the label of the ‘Slipper revolution’, as people took to the streets waving slippers, a well-known weapon for crushing these household pests.32

Another novel development in the wake of the campaign is the emergence of potential challengers from the ranks of the establishment, such as diplomat Vitaly Tsepkalo. They advocate reforms and regime change, but unlike the old nationalist opposition they do not defend pro-Western views. Viktar Babariko, who gathered over 400,000 signatures, has close financial connections with Russia. A former CEO of Belgazprombank he received massive support among the business-oriented urban middle class – and beyond. His arrest on 18 June, allegedly for money laundering, sparked spontaneous street gatherings in Minsk, which were repressed in a way reminiscent of the Winter 2010-2011 crackdown.33

The current spiral of protests and repression makes Lukashenka vulnerable in several ways. Even by deploying administrative resources and coercion, Lukashenka is unable to mobilise his traditional support base among blue collar workers and the elderly, hit hard by the current crisis. A critical mass of previously apathetic Belarusians is now eager for a post-Lukashenka era, and possibly ready to fight for it.

Lukashenka is unable to mobilise his traditional support base among blue collar workers and the elderly, hit hard by the current crisis.

Whereas the loyalty of the force structures seems indefectible, the nomenklatura is more disoriented. In a surprise government reshuffle on 4 June several pro-reform ministers were dismissed, such as Prime Minister Sergei Rumas, replaced by silovik Roman Golovchenko, the former head of the Military Industry authority. Influenced by (dis)information from his own security services, reputedly the most pro-Russian segments of the Belarusian administration, Lukashenka is escalating the state violence which can lead to exactly the Maidan scenario he warns against. Russian-led provocations could exacerbate tensions, and justify Moscow’s interference under the pretext of restoring order in case of riots or a power vacuum.34

Should Lukashenka use repression and electoral manipulation to stay in power, he risks being isolated from the West again, reversing previous steps towards normalisation. As in 2011, this would reduce Belarus’s room for geopolitical manoeuvre, giving Russia a chance to impose ‘deeper integration’, notably in the military field (e.g. building its airbase on Belarusian soil). This would also make regional security more volatile.

A preferable scenario, but also the least likely, is a peaceful power transition to a post-Lukashenka era already in 2020, through an electoral process followed by round-tables or a referendum re-establishing the primacy of the 1994 Constitution, as Viktar Babariko has suggested. In this event, Russia would still enjoy considerable leverage.

Whether this would necessarily limit the EU’s links with Belarus will depend on the EU’s own strategy and its readiness to downplay political divergences and engage with Russia (and the EAEU) in a Grand Bargain over the future of European security architecture. Unless Belarus’s neutrality status is sanctified in the process, there is no guarantee that the country will remain sovereign in such a scenario.

Challenges for the EU

Finding the morally right and mutually acceptable format for relating with Lukashenka, and Putin too for that matter, has always created a dilemma for the EU. Its democratic values prevent it from re-engaging unconditionally with the Belarusian leadership, especially if the latter starts to revert to its repressive habits. Should political prisoners reappear in Belarus the EU will have to decide whether to impose coercive measures against Lukashenka's regime again, with the additional dilemma that amid growing socioeconomic chaos, EU sanctions might inflict serious collateral damage on the Belarusian population too.

Yet the time will come when the EU will have to engage with a post-Lukashenka Belarus. Identifying and reaching out to those in the bureaucracy without whom transition cannot proceed is critically important now. Conversely, continuing conditional engagement without conceding to the forces of pragmatism – which have been on the rise within the EU too – exposes Brussels to being sidelined in future transition processes. Keeping this prospect in mind, the EU should continue a constructive but principled dialogue and technical cooperation on mutually beneficial sectoral issues with carefully selected interlocutors.

Warnings and recommendations made before the sanctions were last lifted remain valid: Lukashenka’s flirting with the West is an authoritarian regime-survival tactic, and after he is gone a hypothetically democratic Belarus would not necessarily be more pro-European.36 Attention should thus focus on the fields where linkages with Europe contribute to consolidating Belarus’s sovereignty, people-to-people contacts with Europe, and strengthening the resilience of civil society in the face of domestic and external challenges. Five directions should be prioritised:

Reducing Belarus’s dependence on Russian energy deliveries. Cooperation in the energy field is the main avenue for enhancing Belarus’s economic resilience.36 This can be done by developing alternative supply routes, supporting the transition to renewables and furthering support for infrastructure and energy projects to ensure deeper interconnectivity of the Belarusian energy system with EU standards.37

Helping Belarus uphold its neutrality pledge, by counter-balancing or deterring military reintegration with Russia. This could mean encouraging a closer partnership between Belarus and NATO as well – and overcoming the resistance of Turkey38 and Lithuania to that prospect.

Sustaining nation-building trends, notably by supporting ‘soft Belarusianisation’. A first step would be for all EU member states to recognise and use ‘Belarus’ to name the country (not ‘White Russia’ or ‘Biélorussie’, terms which refer to the Soviet Socialist Republic of Byelorussia). Support should focus on the media and book publishing fields, which are still dominated by Russian-language products. Belarusian bureaucrats are aware that Russification represents an existential threat for their country’s sovereignty: what they lack are tools, ideas and networks for containing it.39

Building civil society capacity. More and smarter funding is needed for organisations, initiatives and individuals that contribute to making Belarusian civil society more resilient against malign Russian interference. This should include investing in developing media-awareness, and encouraging people-to-people contacts, twinning, as well as cultural and educational exchanges across the EU.

Reinvigorating cross-border cooperation. Available instruments – for example the European Neighbourhood Instrument (ENI) for Eastern Partners – can increase cooperation between Belarusian border regions and Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Ukraine. More synergies could be developed within Euroregions (Bug, Neman, etc.) to foster the socialisation of Belarusians in Europe.

The Europeans are constrained in how far they can respond to Belarusian challenges and possible overtures from Minsk. Acknowledging Belarus’s importance for European security, it is in the EU’s interest, however, to exploit the cracks that have appeared in the façade of the Belarusian-Russian union.40

Russia is evidently trying to coerce Belarus into accepting being either subjugated politically, or abandoned economically, and the hybrid measures used in that blackmail do not exclude the use of conventional force at some point. The sustainability of alternative schemes for future bilateral relations between Belarus and Russia depends on a number of domestic and external unknowns, and possible scenarios at the regional level.41 One thing is certain, however: should Russia wish to take control of Belarus, Lukashenka’s previous balancing game and diversification strategy cannot guarantee his regime’s survival. Amid the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent economic downturn, the EU will predictably have little time and money to spend on Belarus. Yet this is a critically important endeavour, since the prospect of Belarus losing its sovereignty entails risks for European peace and security too.

References

* The author would like to thank Karol Luczka for his assistance with visuals in this Brief.

1 Andrew Roth, “Belarus Blues: Can Europe’s ‘Last Dictator’ Survive Rising Discontent?”, The Guardian, June 16, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/16/slipper-revolution-lukashenkos-reign-under-pressure-in-belarus?fbclid=IwAR3i7tx-rZc058avc640M4u_mXMtMYKzrKW8uZxpvh1ytaenEhPM_GlWyzg.

2 Yauheni Preiherman, “Treaty on the Establishment of the Union State of Belarus and Russia”, Backgrounder no 7, Minsk Dialogue on International Relations, April 1, 2019, https://minskdialogue.by/en/research/memorable-notes/treaty-on-the-establishment-of-the-union-state-of-belarus-and-russia.

3 John Lough and Katia Glod, “Integration on Hold for Russia and Belarus”, Chatham House Expert Comment, January 14, 2020, https://www.chathamhouse.org/expert/comment/integration-hold-russia-and-belarus.

4 Aleś Alachnovič, “Belarus: economic dependence has its upsides”, obserwatorfinansowy.pl, April 14, 2019, https://www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl/in-english/macroeconomics/belarus-economic-dependence-has-its-upsides.

5 Artyom Shraibman, “Money or Sovereignty? What an Oil Dispute Portends for Russian-Belarusian Relations”, Carnegie Moscow Center, January 10, 2019, https://carnegie.ru/commentary/78096.

6 Arseny Sivitski, “Belarus-Russia: From a Strategic Deal to an Integration Ultimatum”, Russia Foreign Policy Papers, Foreign Policy Research Institute, Philadelphia, December 16, 2019, https://www.fpri.org/article/2019/12/belarus-russia-from-a-strategic-deal-to-an-integration-ultimatum.

7 Piotr Petrovskij, “Pochemu Belarus’ i Rossija nie podpisali dorozhnye karty integracii?” [Why did Belarus and Russia not sign road maps for integration?], Eurasia Expert, December 9, 2019, https://eurasia.expert/pochemu-belarus-i-rossiya-ne-podpisali-dorozhnye-karty-integratsii.

8 Artyom Shraibman, “Oil Spoils the Russia-Belarus Romance”, Carnegie Moscow Centre, January 28, 2020, https://carnegie.ru/commentary/80905.

9 Anaïs Marin, “Belarusian Nationalism in the 2010s: A Case of Anti-Colonialism? Origins, Features and Outcomes of Ongoing ‘Soft Belarusianisation’”, Journal of Belarusian Studies, vol. 9, no 1 (2020), pp. 27-50, https://brill.com/view/journals/bela/9/1/article-p27_3.xml.

10 Anaïs Marin, “The Union State of Belarus and Russia. Myths and Realities of Politico-Military Integration”, Vilnius Institute of Political Affairs, June 2020, https://vilniusinstitute.lt/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Marin-Union-State-of-Belarus-and-Russia.pdf.

11 Kamil Kłysiński, “(Un)realistic Neutrality. Attempts to Redefine Belarus’ Foreign Policy”, OSW Commentary, Centre for Eastern Studies, Warsaw, July 2, 2018, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2018-07-02/un-realistic-neutrality-attempts-to-redefine-belarus-foreign-0.

12 Anaïs Marin, ‘Minsk-Beijing: what kind of strategic partnership?’, Russie.NEI.Visions Policy Papers, no 102, Institut Français des Relations Internationales, Paris, June 26, 2017, https://www.ifri.org/en/publications/notes-de-lifri/russieneivisions/minsk-beijing-what-kind-strategic-partnership.

13 James Shotter, “Mike Pompeo says US ready to meet all Belarus’ oil needs”, Financial Times, February 1, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/154f26f8-450f-11ea-aeb3-955839e06441.

14 Mason Clark, “Lukashenka Uses Oil Tariffs to Delay Integration with Russia”, Russia in Review, February 4, 2020, http://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russia-review-belarus-update-lukashenko-uses-oil-tariffs-delay-integration-russia.

15 International Strategic Action Network for Security (iSANS), “Someone will not like it: United States Oil Supplies to Belarus”, Reform.by, May 11, 2020, https://isans.org/en/someone-will-not-like-it-united-states-oil-supplies-to-belarus.

16 Igor Yushkov, “U Belarusov ne ostalos’ rychagov ‘neftyanogo’ davleniya na Rossiyu” [Belarus no longer has any ‘oil’ leverage on Russia], January 16, 2020, https://eurasia.expert/u-belarusi-ne-ostalos-rychagov-neftyanogo-davleniya-na-rossiyu.

17 “Gazprom expects to receive debt payment from Belarus”, Caspian News, May 30, 2020, https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/gazprom-expects-to-receive-debt-payment-from-belarus-2020-5-30-50.

18 Christopher Walker and Jessica Ludwig, “The Meaning of Sharp Power: How Authoritarian States Project Influence”, Foreign Affairs, November 16, 2017, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2017-11-16/meaning-sharp-power. According to their definition “Authoritarian influence efforts are ‘sharp’ in the sense that they pierce, penetrate, or perforate the political and information environments in the targeted countries. (…) Above all, the term ‘sharp power’ captures the malign and aggressive nature of the authoritarian projects, which bear little resemblance to the benign attraction of soft power.”

19 Kamil Kłysiński and Piotr Żochowski, “The End of The Myth of a Brotherly Belarus? Russian Soft Power in Belarus After 2014: the Background and its Manifestations”, OSW Studies no. 58, Centre for Eastern Studies, November 7, 2016, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-studies/2016-11-07/end-myth-a-brot-herly-belarus-russian-soft-power-belarus-after.

20 International Strategic Action Network for Security (iSANS), ”Coercion to ‘Integration’: Russia’s Creeping Assault on the Sovereignty of Belarus – Likely Scenario of a Takeover, Channels of Influence and the Main Actors”, 2019, https://isans.org/en/isans-publishes-a-brief-version-of-the-report-coercion-to-integration-russias-creeping-assault-on-the-sovereignty-of-belarus.

21 International Strategic Action Network for Security (iSANS), “Re-Building of the Empire: Behind the Facade of Russia-Belarus Union State: The System of Russian Influence in the Public and Political Spheres of Belarus”, Summary of the iSANS analytical report, December 12, 2019, https://isans.org/en/re-building-of-the-empire-behind-the-facade-of-russia-belarus-union-state.

22 Veranika Laputska and Aliaksandr Papko, “Belarus”, in Volha Damarad and Andrei Yeliseyeu (eds.), Disinformation Resilience in Central and Eastern Europe (Kyiv: Disinformation Resilience Index project and Bratislava: Strategic Policy Institute, 2018), pp. 69-100, https://stratpol.sk/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DRI_CEE_2018.pdf. Russian translation available here: https://east-center.org/information-security-belarus-challenges.

23 Mathieu Boulègue, Orysia Lutsevych and Anaïs Marin, “Civil Society under Russia’s Threat. Building Resilience in Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova”, Chatham House Report, November 8, 2018, https://www.chathamhouse.org/publication/civil-society-under-russias-threat-building-resilience-ukraine-belarus-and-moldova.

24 Op. Cit., “Belarusian Nationalism in the 2010s: A Case of Anti-Colonialism?”

25 Keir Giles, “What Next for Russia’s Front-Line States?”, The Letort Papers, Strategic Studies Institute and US Army War College Press, February 2019, pp. 4-15, https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/what-next-for-russias-front-line-states.

26 Gregory Feifer, “Russia: In Surprise Move, Putin Backs Russia-Belarus Merger; Lukashenka Rebuffs Plan”, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, August 15, 2002, https://www.rferl.org/a/1100542.html.

27 ‘Sotsoprosy: vysokaya elastichnost’ geopoliticheskikh orientatsiy’ [Surveys show high elasticity of geopolitical orientations], nmnby.eu, January 15, 2020, https://nmnby.eu/news/analytics/7015.html?fbclid=IwAR1O9FxONAmc3FiGKtv6u6KbqpDYIEw78ixzBfXfXEzqnTteaCuz7OH-U3g.

28 Artyom Shraibman, “A Neutral Nation. What do Belarusians Think about the World around Them?”, PACT study, March 12, 2020, https://www.pactworld.org/news/what-do-belarusians-think-neutral-nation-what-do-belarusians-think-about-world-around-them.

29 Arseny Sivitsky, “Kremlin Considers Renewed Interference in Belarus Under Guise of Coronavirus Crisis Response”, Eurasia Daily Monitor, vol. 17, no. 77, June 1, 2020, https://jamestown.org/program/kremlin-considers-renewed-interference-in-belarus-under-guise-of-coronavirus-crisis-response.

30 Arkady Moshes and Ryhor Nizhnikau, “The Belarusian Paradox. A Country of Today Versus a President of the Past”, FIIA Briefing Paper, no. 265, June 2019, https://www.fiia.fi/en/publication/the-belarusian-paradox.

31 “Alexander Lukashenko threatens to execute the peaceful demonstrators by firing squad”, Our House, International Centre for Civil Initiatives, June 9, 2020, https://news.house/40767.

32 “Belarus’s ‘Slipper Revolution’ seeks to stamp out Lukashenka. Is he at risk?”, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 6, 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-s-slipper-revolution-seeks-to-stamp-out-lukashenka-is-he-at-risk-/30656256.html.

33 Artyom Shraybman, ‘Artyom Shraybman. Shutki konchilis’. Spiral’ eskalyatsii vediot stranu k krovi’ [Artyom Shraybman. Jokes are over. The spiral of escalation is leading the country to bloodshed], TUT.BY, 2020, June 22, 2020, https://news.tut.by/economics/689724.html.

34 Op. Cit., “Kremlin Considers Renewed Interference in Belarus…”

35 Yaraslau Kryvoi and Andrew Wilson, “From Sanctions To Summits: Belarus After the Ukraine Crisis”, ECFR Policy Memo no. 132, May 5, 2015, https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/from_sanctions_to_summits_belarus_after_the_ukraine_crisis3016.

36 Veranika Laputska, “No Easy Future. What Can the Eastern Partnership Bring to Belarus?”, Visegrad Insight, May 31, 2020, https://visegradinsight.eu/belarus-no-easy-future-eap2030.

37 Joerg Forbrig and Wojciech Przybylski, “Eastern European #Futures: Scenarios for the EaP 2030”, Visegrad Insight, Special report issue, vol. 16, no.1, 2020, p. 9, https://visegradinsight.eu/eap2030.

38 Keir Giles, “Belarus’s Balancing Act Continues: Minsk Fends Off The ‘Ukraine Option’ Again”, Federal Academy for Security Policy, Security Policy Working Paper, no. 11, 2017, https://www.baks.bund.de/en/working-papers/2017/belaruss-balancing-act-continues-minsk-fends-off-the-ukraine-option-again

39 Op. Cit., ‘Civil Society under Russia’s Threat’.

40 Op. Cit., ‘The Union State of Belarus and Russia. Myths and Realities of Politico-Military Integration’.

41 Op. Cit., ‘Eastern European #Futures: Scenarios for the EaP 2030’.