You are here

Sahel reset: time to reshape the EU's engagement

Introduction

The coup of 26 July in Niger marked a turning point in the politics of the Sahel. Its timing surprised local and international observers alike because of the perceived relative stability of Niger in comparison to Mali and Burkina Faso. The wave of coups in these three countries starkly exposed the dilemma faced by the EU as it sought to simultaneously pursue its strategic interests while also upholding democratic values (1). Caught offguard by events on the ground, the EU was forced to confront the complexities of its role in a region where structural vulnerabilities hinder the emergence of sustainable institutions, economic development and security (2).

Data: UN OCHA, 2024; ACLED, 2024; IOM, Migration Data Portal, 2024

This Brief analyses the EU’s engagement in the Sahel region in light of the recent coups and the challenges the Union faces in balancing norms and interests. It offers insights into the shortcomings and complexities of the EU’s initiatives in the Sahel and puts forward recommendations for future engagement in a region that remains strategic for the EU’s security, the wider Western Africa region, and the Union’s relations with Africa more broadly. The extent to which the EU will be able to maintain its engagement in the Sahel while upholding its values will in the long term depend on developments following the coups. However, to prepare for this far-reaching endeavour, the EU could foster diplomatic engagement to accompany transitions, pursue human and community development to prevent further exacerbation of grievances and enhance planning coordination to amplify its potential for impact.

A costly standoff

The regimes that recently came to power through unconstitutional changes of government in the Sahel have displayed similar postures, expressing their dissatisfaction with the ineffectiveness of civilian governments in fighting terrorism and insecurity, and resentment of perceived post-colonial influence. As the coups unfolded and met with increasingly severe condemnation from international actors, the regimes reacted by denouncing the agreements with France and rejecting EU deployments at an increasing tempo. Thus, Mali obtained the withdrawal of the French missions, Takuba and the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), Burkina Faso did likewise with the French Operation Sabre, and Niger’s National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland (CNSP) denounced the agreements for EUCAP Sahel Niger and the EU Military Partnership Mission (EUMPM) on 4 December 2023. In parallel, the three countries also withdrew from the G5 Sahel, and coalesced into a rival Alliance of Sahel States in September 2023. Conceived as an alliance for mutual self-defence and assistance, its articles 5 and 6 provide for collective defence against aggression and insurgencies, including terrorism. The Alliance also includes the option for other countries to join (art. 8 and 11) with a possible reference to Guinea (which experienced a coup in 2021) and other coastal states, as indicated by the commitment given by three landlocked states not to blockade the ports and coasts of another country (3).

Overall, the hardline response to the coups has proved ineffective.

The international response to coups in the Sahel differed in intensity, with a relatively low-key response to Burkina Faso, Niger eliciting a tougher stance, and Mali’s protracted transition requiring continued negotiations with the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS). Inconsistencies in approach and the strong reaction to Niger’s coup further escalated tensions with the new military authorities. Intent on preserving power, they promptly denounced mission agreements, revoked a migrant smuggling law, called for citizen mobilisation against a possible ECOWAS military intervention, and launched fundraising efforts in response to sanctions and aid cuts. Overall, the hardline response to the coups has proved ineffective so far. There has been limited progress in transition to civilian rule, a competing order has emerged vis-à-vis ECOWAS, the EU has become increasingly isolated, President Bazoum remains under house arrest, and military authorities have increasingly sought alternative partnerships, e.g. with Russia, while declaring their withdrawal from ECOWAS (4). Meanwhile, terrorist groups exploit the situation, strategically allowing state forces and other armed groups to fight each other. The new authorities’ approach to security remains focused on military actions, resulting in the flaring-up of past disputes. In Mali, the Coordination of the Azawad Movements (CMA), a signatory of the 2015 Algiers Peace Agreement, re-engaged in armed fighting against government forces and Wagner units following the progressive withdrawal of MINUSMA. Burkina Faso experienced inter-ethnic conflicts that increased following the establishment of the Volunteers for the Defence of the Homeland. Niger appears to be increasingly at risk of following a similar path to further instability.

EU-Sahel dynamics: Timeline 2011-2024

In this context, alternative partnerships to the EU sought by transitional authorities, notably with Russia, remain mostly focused on defence – and more recently have expanded to the extractive sector. Thus, their potential for addressing the underlying factors that allegedly led to unconstitutional changes of government is at least debatable.

In large portions of the Sahel, several actors are engaged in fierce competition for territorial control and access to resources. However, this competition also involves key state-building issues: power sharing between the centre and periphery, inclusion and exclusion, the role of religion in public life, and the distribution of resources. These important questions extend beyond the issue of coups and highlight the importance of transitions. Accordingly, long-term solutions are more likely to be political than military, emphasising the need for regional and international organisations to continue engaging to favour the emergence of inclusive political processes.

Twelve years of EU engagement in the Sahel: Learning by doing

In 2011, the EU adopted its first strategy for the Sahel, targeting development, governance, conflict resolution, diplomacy, security, the rule of law and countering violent extremism. By 2015, the strategy had expanded to include migration and support for the G5 Sahel, a regional coordination framework established by Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad for security and development. In addition, between 2013 and 2023, the EU, its Member States, the United Nations (UN) and neighbouring countries deployed several military, civilian or multidimensional missions with different executive or non-executive mandates. These included deployments in support of the fight against terrorism (Barkhane, Takuba, and the Multinational Joint Task Force against Boko Haram – MJTF), capacity building (EUTM Mali, EUCAP Sahel Mali and Niger), and protection of civilians, police and political functions (MINUSMA). At the same time, several politico-diplomatic forums emerged to address the security-development nexus in the Sahel, to support the G5 Sahel, to foster coordination, and keep donors and partners (the Sahel Alliance, the Partnership for Security and Stability in the Sahel – P3S, and the Coalition for the Sahel) engaged. However, pressure on the latter to produce evidence of results proved counterproductive. Moreover, difficulties affecting the operationalisation of the G5 Sahel, spiralling insecurity, and the first coup in Mali highlighted the shortcomings of this approach.

Thus, the EU’s 2021 Integrated Sahel Strategy sought to promote a more holistic approach based on governance and civilian involvement. This revamped strategy aimed to address deteriorated political and security conditions by putting renewed emphasis on politics and civilian administrations. In the Sahel, there was widespread frustration due to the perceived incapacity of governments to ensure security and basic services, and the perception of widespread corruption. External shocks, including the global Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and growing internal displacement, intensified economic and social pressure on already fragile economies and states.

The EU’s approach in the Sahel suffered from process shortcomings and the effects of local fragilities rather than from a flawed analysis of the situation.

The EU’s approach in the Sahel suffered from process shortcomings and the effects of local fragilities rather than from a flawed analysis of the situation.

First, it showed signs of impatience by relying on multiple platforms and relatively tight roadmaps. In effect, it supported national and regional forces to address security and development needs, also as a means to keep partners engaged. Military-focused methods sought quick gains against terrorism but lacked coordination with preventive measures. Strategies for fighting violent extremism, promoting development and providing basic services were often disconnected from security-oriented action, undermining the potential for added value and mutual reinforcement. The Coalition for the Sahel and similar coordination platforms kept international donors engaged, enhanced coordination efforts, and fostered horizontal coordination among hierarchical national administrations in partner countries. However, they also increased pressure to deliver on national actors with limited administrative capacities and often understaffed EU Delegations. Additionally, due to countries’ reliance on external financing, there was often an increased emphasis on external accountability and swift delivery of outcomes rather than the quality of the latter.

Second, the EU’s initiatives lacked focus and were over-ambitious. By wanting to support most aspects of national programmes, its actions remained scattered, despite increased efforts at coordination. Regardless of the fact that the EU allocated significant financial resources to the Sahel, the level of ambition of its strategy would have probably required much bigger investments due to limited domestic revenues and increased local ownership. On average in the G5 Sahel, EU institutions allocated about €170 million per country per year between 2014 and 2020 (5). Niger alone announced that its budget for 2023 would be €4.8 billion, including €2.6 billion (54.38 %) of external financing (6) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) suggested that an additional €26 billion would be required over 2023-2026 to relaunch a development process in the Sahel (7).

Third, the EU overestimated the immediate impact of its 2021 integrated strategy. Due to the EU’s internal procedures and divisions among Member States, the translation of revised priorities into action took months. Approved in April 2021, EUCAP Sahel Niger’s mandate included it officially in its following mandate revision in October 2022, and in Mali in May 2022 through the Holistic Strategic Review of EUTM Mali and EUCAP SAHEL Mali (8). In between, the delays in the approval of the regulation for the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) Global Europe offered the unintended opportunity for some coordination in the planning of development projects, and of CSDP civilian missions in reinforcing justice, security and state presence. Thus, in Niger for instance various EU actors (CSDP missions, EU Delegations, and headquarters) seized the opportunity for enhanced coordination at technical level to foster the implementation of the political goals of the integrated approach. In Burkina Faso, enhanced coordination emerged informally following the EU Council conclusions on Operationalising the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus in 2017, despite the fact that it was not one of the pilot countries (9).

Coordination at EU level remained too complex, hindering joint planning processes.

Fourth, the 2021 strategy failed to consider the time required for substantial improvements in governance, inclusivity, security sector reform and economic development (10). While these objectives aim to address the root causes of extremism, insecurity and coups, they are projected to be lengthy endeavours that depend on national trajectories and the willingness and capacity of national institutions to implement reforms and enhance domestic accountability. These structural limitations obviously impacted the strategy’s implementation, hampered by various challenges and setbacks, and further disrupted by coups. This indicates the importance of incorporating contingency planning and mitigating the presumed direct connection between EU action and outcomes.

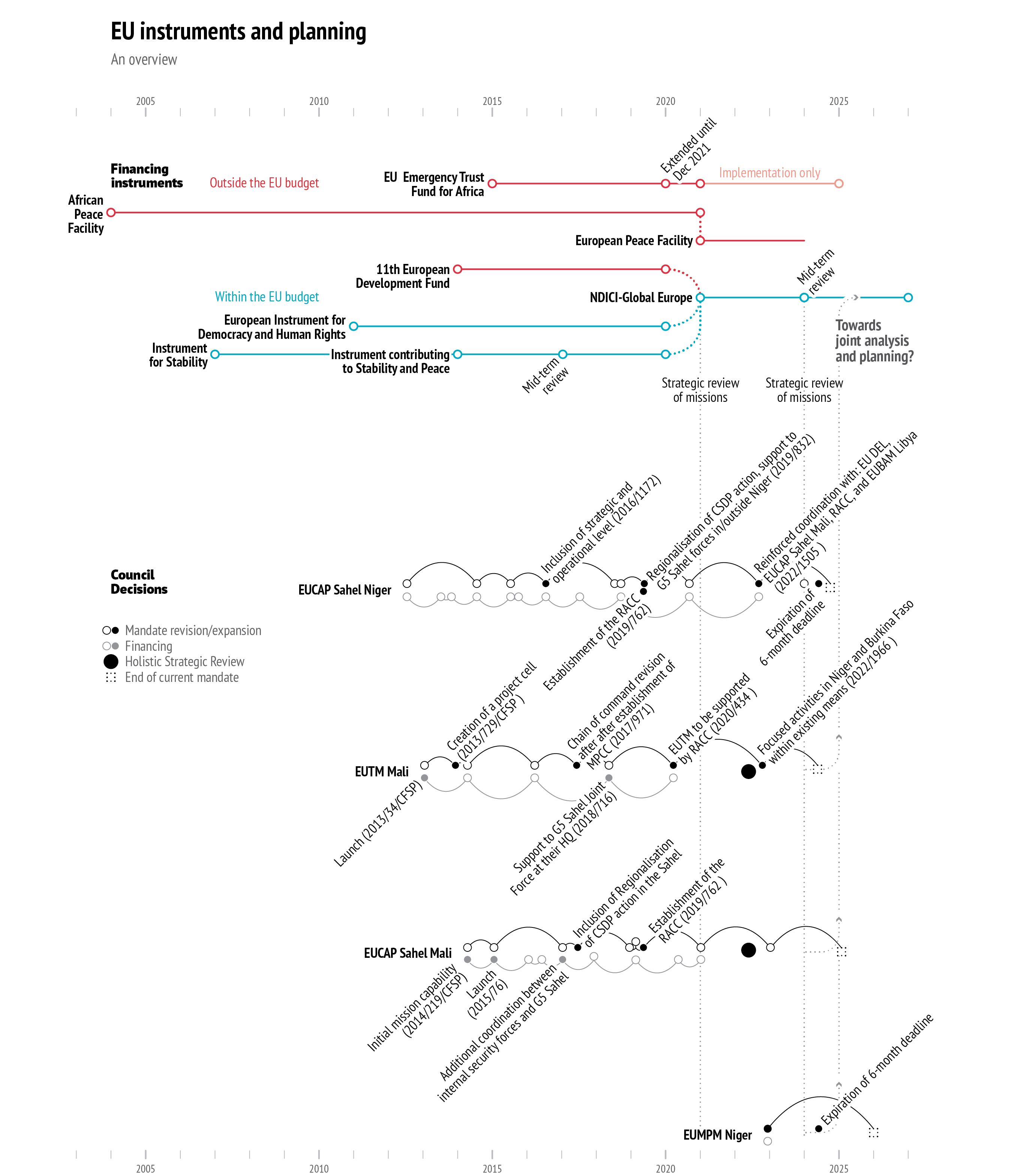

Finally, coordination at EU level remained too complex, hindering joint planning processes. While development cooperation followed the seven-year cycle of the EU budget, with mid-term adjustments, the budget of CSDP missions was constantly under revision. Other financial instruments (the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, the African Peace Facility, the Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace until 2020 and NDICI and the European Peace Facility from 2021) followed different financial and planning cycles. The fact that different actors exercised planning and institutional authority over the various funding instruments ultimately generated an increasing burden of coordination of already planned actions in different domains with their own cycles. Overall, the EU is learning by doing and improving its coordination efforts as also shown by initiatives such as Team Europe which expanded from Covid-19 response to other domains. However, real concerted planning for greater impact is yet to materialise. In Mali, only in the aftermath of the coup did EU institutions, Member States, as well as Switzerland and Norway, develop joint programming (11). Thus, while concerted planning clearly cannot alone overcome local structural fragility, it can help the EU streamline its action and increase its chances for impact.

A starting point for the EU's reset

Despite facing such a challenging context, the EU’s interest in the Sahel remains strong. Security issues are still relevant to the region’s wider overall stability; illicit trafficking and human smuggling are still a challenge; energy corridors with Africa, mineral resources, and green transitions are still in the EU’s interest. In addition, in an increasingly fractious global order, more contestation, instead of diplomacy, risks having an even more adverse impact on a rule-based approach. In the Sahel, the experience with the recent series of coups shows that a hardline stance based on the imposition of sanctions leads to worse conditions for the population, accrued influence of rival powers, rising nationalism, and increased violations of international humanitarian law and human rights. These only benefit extremist groups by expanding their territorial control or fuelling radicalisation.

While these ongoing trends pose significant challenges, the EU’s long-term interests and values can be reconciled by looking at the potential for EU engagement to yield positive results after transitional periods. If the EU envisions a Sahel characterised by inclusivity, democratic processes and human security, it must not step back or adopt a risk-averse approach to the current challenges. Instead, it should leverage its diplomatic outreach to engage actively and support the values for which it stands, alongside its interests. At the same time, the EU should acknowledge that engagement is a long-term commitment, and tangible results will not materialise immediately. It will likely be a lengthy journey towards resetting its engagement and overhauling its operational processes as well as contributing to addressing the root causes of insecurity, migration and democratic shortcomings.

If the EU wishes to pursue its commitment to engaging with the Sahel region and upholding its values even following the coups, the following recommendations provide practical avenues for its involvement.

At the regional level:

- Promote diplomatic coordination within ECOWAS and the African Union, while supporting reforms to prevent further coups: term limits, inclusive political processes, access to justice, press freedom, and trust among institutions.

- Strengthen regional capacities for transitions and prioritise inclusive processes over strict timelines.

- Avoid competition for mediating roles with transitional authorities and further escalation of tensions.

At national level:

- Resume communication with de facto authorities, while clearly conveying the EU’s red lines which most likely will exclude budget support and equipment. A differentiated yet coherent approach would allow national specificities to be taken into consideration while avoiding allegations of double standards.

- Emphasise the contribution of civil society (including diasporas) to national dialogues on transitions, e.g. in the forthcoming dialogue in Niger, but also at local level in preventing radicalisation and violence. It has been demonstrated that local peace processes help reduce humanitarian needs (12), and if these processes are supported over the longer term their impact can be amplified.

- Prioritise areas such as justice (including traditional justice), education, agriculture and health as domains that help address immediate needs while strengthening long-term resilience; and community-based approaches that may take longer but have a greater chance of sustainable impact (13).

In Niger, the EU could:

- Continue to support ECOWAS mediation.

- Decide on the future of the CSDP missions. Withdrawing EUCAP Sahel Niger may lead to a loss of negotiating power, country knowledge and social capital, and make it impossible to follow up on projects already started. Despite the fact that the window of opportunity appears to be closing rapidly, the EU should consider whether negotiating the mission’s ongoing presence in the country, a longer transition towards termination, or alternative formats may be suitable and viable, also given that established relations may deter an alternative partnership from fully developing. If the EU terminates or relocates EUCAP, it should consider integrating some of its personnel into the EU Delegation to limit losses of expertise.

- Invest in consolidating funded projects, by combining humanitarian, development and peace efforts in relatively more stable regions like Agadez, which is strategic for illicit trafficking, natural resources and migration routes, and Tahoua, where the EU has already invested significantly.

In Mali and Burkina Faso, the continued escalation of violence, including intercommunal violence, and the termination of the Algiers Peace Agreement is a cause of grave concern. The EU could:

- Advocate for a return to the negotiating table among parties to the Algiers Peace Agreement.

- Invest in local peace processes, starting from southern Mali and central Burkina Faso, to avoid further stigmatisation of communities, in particular the Fulani.

Planning and communication have a particular role in determining impact. To streamline its engagement in the Sahel and beyond, the EU should:

- Avoid transferring European troops to neighbouring countries, given increasing opposition in the region to foreign military presence, which existed even before the coups. In 2022, a survey showed that 64% of interviewees in Niger thought the government should not rely on foreign military forces (14).

- Strengthen the EU’s political focus by allocating resources to political sections in EU Delegations.

- Improve strategic communication on CSDP missions and broader EU engagement to prevent misinterpretation of objectives.

- Enhance civilian efforts through improved planning and coordination within the EU and with Member States for greater impact, drawing lessons from field experience, like the implementation of the humanitarian-development-peace nexus in Burkina Faso. Include civil society in conflict and risk analysis, as well as planning, and avoid exclusive emphasis on geographical priorities to prevent resource competition. The strategic review processes for the CSDP missions in the Sahel and the NDICI mid-term review, foreseen in 2024, contain the potential to turn into a broader conflict analysis, lessons learning and planning exercise.

References

* The author would like to thank several colleagues for their comments on earlier drafts, as well as Adam Eskang for his research assistance and Christian Dietrich for his work on the graphics.

1. Wilén, N., ‘Have African coups provoked an identity crisis for the EU?’, Egmont Policy Brief No 323, December 2023 (https://www.egmontinstitute. be/app/uploads/2023/12/Nina-Wilen_Policy_Brief_323_vFinal2. pdf?type=pdf).

2. Ero, C. and Mutiga, M., ‘The crisis of African democracy: Coups are a symptom – not the cause – of political dysfunction’, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 103, No 1, 2024.

3. ‘Charter of Liptako-Gourma establishing the Alliance of Sahel States between: Burkina Faso, The Republic of Mali, the Republic of Niger’, September 2023 (https://maliembassy.us/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ LIPTAKO-GOURMA-Engl-2.pdf).

4. Art. 91 of the ECOWAS Revised Treaty (former art. 64) stipulates a one-year notice period to be given to the ECOWAS Executive Secretary. ECOWAS Commission, ECOWAS Revised Treaty, 1993 (https://www. ecowas.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Revised-treaty-1.pdf).

5. Calculation based on EEAS, ‘L’Union européenne et le G5 Sahel un partenariat plus que jamais d’actualité’, April 2020 (https://www.eeas. europa.eu/sites/default/files/factsheet_eu_g5_sahel_updated.pdf).

6. Republic of Niger, Ministry of Finance, Présentation Solennelle à l’Assemblée nationale du Projet de Loi de Finances au titre de l’année budgétaire 2023, 2022 (http://www.finances.gouv.ne/index. php/une/919-projet-de-loi-des-finances-au-titre-de-l-annee- budgetaire-2023#).

7. IMF, ‘The Sahel, Central African Republic face complex challenges to sustainable development’, IMF Country Focus, 16 November 2023 (https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2023/11/16/cf-the-sahel-car- face-complex-challenges-to-sustainable-development).

8. Council of the European Union, ‘Holistic Strategic Review of EUTM Mali and EUCAP SAHEL Mali 2022’, 9516/22, 25 May 2022 (https://media. euobserver.com/ce019f3357aff2c61c7717085550bacb.pdf).

9. ECDPM and Particip GmbH, study for the European Commission, ‘HDP Nexus: Challenges and Opportunities for its Implementation–Final Report’, November 2022 (https://international-partnerships.ec.europa. eu/system/files/2023-05/eu-hdp-nexus-study-final-report-nov-2022_ en.pdf).

10. Booth, D., ‘Achieving governance reforms under pressure to demonstrate results: Dilemma or new beginning?’ in OECD, A Governance Practitioner’s Notebook: Alternative Ideas And Approaches, 2015 (https://www.oecd. org/dac/accountable-effective-institutions/governance-practitioners- notebook.htm).

11. ‘Programmation Conjointe Européenne au Mali 2020-2024’ (https:// international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/mip- 2021-c2021-9376-mali-annex_fr.pdf).

12. Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, Mediation of Local Conflicts in the Sahel Burkina Faso, Mali & Niger, 2022 (https://hdcentre.org/wp-content/ uploads/2022/09/HDC-PUBLICATION-mediationconflits-Sahel-ENG- WEB.pdf).

13. Raineri, L., ‘Sahel Climate Conflicts? When (Fighting) Climate Change Fuels Terrorism’, Brief No 20, EUISS, November 2020 (https://www.iss. europa.eu/content/sahel-climate-conflicts-when-fighting-climate- change-fuels-terrorism).

14. Ali Bako, M.T., ‘Terrorisme : Les Nigériens sont satisfaits de l’implication de leur armée et ne veulent pas de l’aide d’une armée étrangère’, Dépêche No. 65, Afrobarometer, 19 June 2023 (https://www. afrobarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/AD653-Nigeriens- rejettent-laide-dune-armee-etrangere-Afrobarometer17juin23.pdf).