You are here

Doubling down on desperation: the implications of defunding UNRWA for Palestinian refugees and Lebanon’s security

At first glance Lebanon offers a fleeting glimpse of normalcy, with bustling bars and a busy nightlife. However, this façade masks the harsh reality of life in the country. 80 % of Lebanese citizens live in poverty. Even the annual influx of the two million strong Lebanese diaspora every summer, injecting billions into the economy (approximately $10 billion in 2023), cannot alleviate the deep economic crisis affecting the country. Lebanon’s economic woes are well-documented, ranking among the top ten, if not the top three, most severe global crises of this kind recorded since the mid-nineteenth century

Lebanon’s fragility is further exacerbated by the fact that the country hosts the highest number of refugees per capita and per square kilometre in the world. The conditions at the Shatila refugee camp in Ghobeiry are concerning, as documented during a recent visit by the author. Syrian and Palestinian families endure abysmal conditions, as highlighted by the 2022 cholera outbreak. A staggering 90 % of Syrian and 93 % of Palestinian refugees live in poverty and are unable to meet their basic needs.

Adding to the plight of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Gaza, seventeen major donors, including several European states, recently followed the US in cutting funds for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). This decision stemmed from unproven accusations levelled against UNRWA staff by the Israeli government which has killed 30 000 Palestinians since the Hamas assault on Israel on 7 October. Israel accused 12 UNRWA personnel in Gaza, out of the 13 000 who serve, of involvement in the Hamas 7 October attack.

Following the accusations, on 26 January the UNRWA Commissioner-General, Philippe Lazzarini, decided to immediately terminate the contracts of the staff members allegedly involved in the attacks. The highest investigative body in the UN, the Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS), opened an inquiry into these claims at the UN Secretary-General's request. The Commissioner-General joined a chorus of critics in calling the funding cuts ‘irresponsible’, highlighting their devastating impact on refugees already grappling with war, displacement and regional instability. The European Commission has not suspended support to UNRWA, however. The EU High Representative Josep Borrel echoed Lazzarini’s concerns, deeming the decision ‘dangerous’ and underscoring the potential consequences. At the beginning of March the European Commission pledged to release €50 million in funding to UNRWA and to allocate an extra €68 million in humanitarian aid to the Palestinians in 2024.

In Lebanon, security officials have warned of a ‘social explosion’ if UNRWA funding cuts continue. Defunding plunges Palestinian communities deeper into hardship, jeopardising not only their lives but also Lebanon’s fragile security. If the EU and other international actors including Arab states want to avoid Lebanon descending into violence, they need to ensure UNRWA has the funding to effectively carry out its mission.

Defunding plunges Palestinian communities deeper into hardship, jeopardising not only their lives but also Lebanon’s fragile security.

The impact of UNRWA cuts on Palestinian refugees in Lebanon

Established in 1949 to support the tens of thousands of Palestinians forcibly displaced from their homes during the 1948 Nakba, UNRWA has served as a lifeline for generations of Palestinian refugees. The agency provides vital services to 200 000 refugees across 12 camps in Lebanon, but existing US sanctions have already strained its ability to deliver critical assistance.

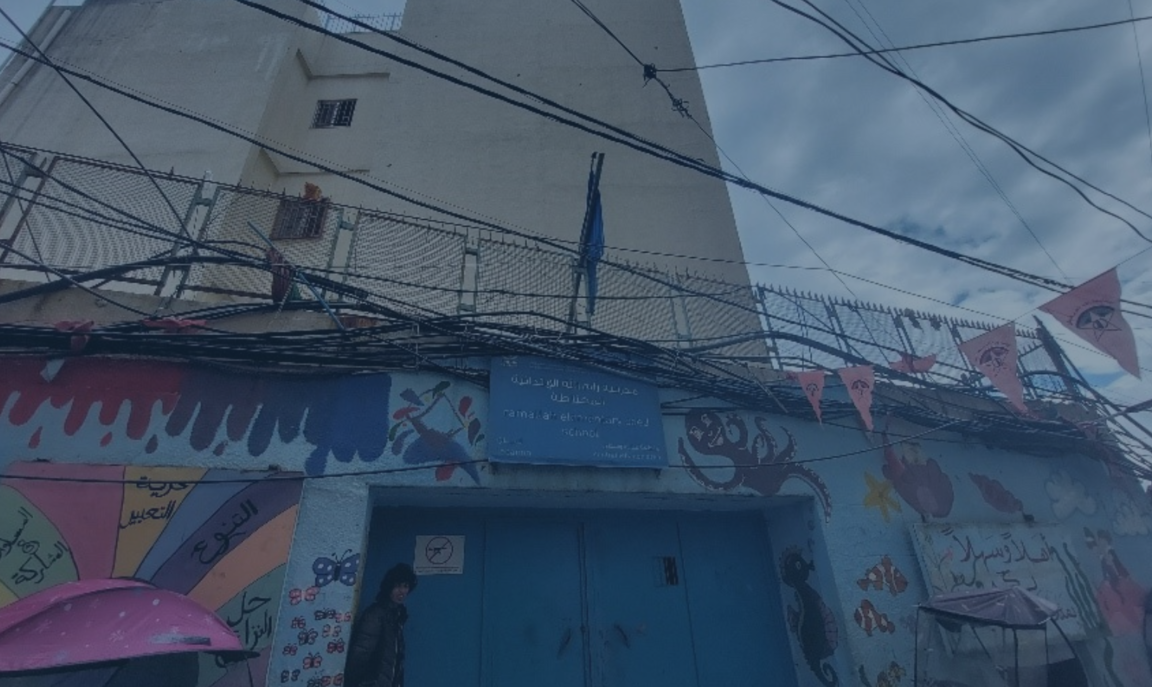

Access to Shatila camp was made possible with the support of the National Institution of Social Care and Vocational Training (NISCVT), a non-sectarian and non-governmental humanitarian organisation. This sprawling community, now home to four generations of Palestinian refugees, covers an area of roughly one square kilometre and is home to over 50 000 people, including Palestinians, Syrian-Palestinians, Syrians, Egyptians and other nationalities.

The camp presents a bleak scene of poverty and hardship. Densely packed homes crowd the alleyways, casting long shadows that add to the oppressive atmosphere. The constant hum of generators competes with the din of scooters navigating the narrow streets. The air is thick with the stench of uncollected rubbish, making it difficult to breathe. But Shatila camp thirsts for more than just breathable air. Residents denied the basic right to clean water have resorted to digging wells for seawater. Though desalinised by a local shop, the ‘suitable’ water, sold by the gallon, is a constant reminder of their plight. In this atmosphere of scarcity, news of UNRWA cuts has been greeted with dismay.

First, education, which has long been a beacon of hope for the population, faces deep cuts. UNRWA operates 65 schools across Lebanon, educating nearly 40 000 children. Among Palestinian refugees, education is a source of immense pride and represents the only path to a future. Oum Ghassan, a 70-year-old widow who raised nine children in the camp, reflects: ‘We lost everything; we have no country and no passport, but our kids are educated. Education is our lifeline. I had nine children, and thanks to UNRWA they are all educated. Stopping UNRWA funding is like killing our future, which is already nonexistent’. Her words echo those of Oum Walid: ‘Education is our children’s weapon. These cuts kill our hope’. Another resident, whose son has special needs, says the UNRWA school provides an essential service: ‘Without it, he’d be lost. It offers not just knowledge, but hope and opportunities to socialise with other children as well’.

Second, there is healthcare. UNRWA operates 27 health centres, providing an average of 595,000 patients with medical treatment annually. One resident with diabetes worries, ‘What will I do when the UNRWA clinic closes? How will I access medication?’ Another, whose daughter has thalassemia, a serious blood condition, pleads, ‘Her life depends on UNRWA support. If it ends, her days are numbered. My daughter’s access to proper healthcare and nutrition is already limited, and these cuts will only make it harder for her’.

Third, UNRWA’s monthly food assistance reaches 114,000 refugees, roughly 57 % of the population in Lebanon. This assistance remains critical for many. A widow, who is a mother of two, confides: ‘Forty-five dollars, every three months—it’s nothing, but here, it means survival. Taking it away leaves us with what option? Begging? Stealing?’.

Fourth, UNRWA serves as a crucial lifeline for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, offering them employment opportunities amidst severely limited options due to restrictive labour laws. With around 3 500 employees, UNRWA represents a significant source of income for 10-15 % of the registered Palestinian refugee population in the country. For instance, the garbage collection in Shatila is done by young people from the camp. While these jobs may not be ‘ideal’, residents acknowledge the importance of supporting each other. Kassem Aina, General Director of the NISCVT, summarises the situation: ‘Our young people have PhDs, yet they collect garbage. It’s not ideal, but they do it for the sake of the community. They do it for the Palestinian cause. We need to help each other’.

UNRWA serves as a crucial lifeline for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

Further funding cuts to UNRWA would not only mean thousands of refugees losing their jobs, worsening their hardship, but also exacerbating the already inadequate waste management in the camps. The camp’s high population density already strains UNRWA’s efforts, as aid worker Achwak explains: ‘Before, there were 500 families. Now, we’re 50,000. Without UNRWA, the streets would drown in garbage within two days. Already on weekends, the streets are full by Monday’. This highlights the critical role played by UNRWA in maintaining basic sanitation and preventing further health risks for the residents of the camp.

While UNRWA faces challenges with vocational programmes and cash transfers, residents agree its help is crucial. As Oum Walid states, ‘Even if UNRWA isn’t perfect, it’s our crutch, our walking stick. We need it to stand’.

The future of Palestinian refugees in Shatila and across Lebanon hangs in the balance. Withdrawing UNRWA’s lifeline would not just dismantle decades of support; it would extinguish hope, jeopardising Lebanon’s social and security situation.

Beyond the headlines: UNRWA defunding and Lebanon’s future

While having to contend with misinformation and disinformation campaigns, UNRWA has acknowledged its flaws and is actively undertaking reforms. However, defunding the organisation is a counterproductive solution. Despite operating in complex environments controlled by armed groups, UNRWA maintains transparency and has systematically documented its activities. Since 2022, 66 investigations have addressed a range of allegations related to impartiality violations, representing only 0.22 % of its 30,000 staff members, and not all of these cases have been substantiated. Therefore claims that the institution as a whole is ‘totally infiltrated’ are unfounded.

The defunding of UNRWA poses a significant threat in Lebanon, with potential consequences ranging from immediate humanitarian crises to destabilising shifts in the political landscape. The most immediate concern is that it will lead to an increase in people embarking on dangerous sea journeys to escape their situation. The recent disappearance of two Palestinians from Shatila who attempted a perilous boat crossing to Europe underlines this risk. ‘The sea feels like a better option than this endless cycle of poverty and hopelessness’, a resident lamented.

This echoes the recent waves of refugees fleeing Lebanon, including Syrians and Lebanese citizens attempting to reach Cyprus, just 175 kilometres away. Should this exodus occur, it would cause widespread suffering, necessitating a collaborative response between domestic authorities and their European counterparts in receiving countries.

In the medium to long term, several critical issues may trigger rising inter-factional tensions within the camps, increasing friction between refugees and local populations outside the camps, and the trend of youth radicalisation within the camps. The denial of basic rights and opportunities creates a desperate environment ripe for radicalisation and unrest. The treatment of Palestinians in Lebanon stands in sharp contrast to their experiences in neighbouring countries like Syria or Jordan.

The denial of basic rights and opportunities creates a desperate environment ripe for radicalisation and unrest.

While Palestinians in Jordan for the most part enjoy citizenship, hold positions of power in the economy and government, and have the freedom to work, those in Lebanon face severe restrictions, such as having no rights to property ownership, investment, or most forms of employment. Access to a large number of professional occupations remains largely off-limits due to regulations based on sectarian discrimination. Palestinians are barred from over 72 professions. Even in basic sectors like construction, sanitation and agriculture, where Lebanese labour laws technically require work permits for non-citizens, Palestinians are forced into low-wage jobs with no security or benefits.

The worsening living conditions in the camps, risk pushing some down a dangerous path for which Lebanon and its security forces are ill-prepared. According to Dr. Mohanad Hage Ali, deputy director for research and senior expert analyst at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, Hamas’s rising popularity is already driving a significant shift in the camp dynamics. One resident, who was born in the camp and works as a social worker, explained: ‘Everything is ripe for an explosion [...] Hamas is more popular today because of their fight and courage in Gaza, and joining them offers a tempting $300 monthly stipend for fighters.’ This scenario is alarming given the history of armed conflict within the camps and throughout Lebanon.

To avert these consequences, it is crucial to restore funding to UNRWA for both humanitarian and security reasons. Addressing the UNRWA defunding issue in Lebanon requires immediate action and a long-term vision for the EU and other international partners including Arab states. This means taking the necessary steps to address the short-term humanitarian needs, strengthening the Lebanese state’s capacity, and ensuring continued support for UNRWA. Failing to tackle the challenges could have grave long-term repercussions for Lebanon’s security and, by extension, for regional stability.